By design, the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) work follows a predictable, seasonal rhythm: budget guidance to agencies in the spring, strategic management reviews in the late summer, passback in the fall, shutdown saber-rattling in late September, release of the president’s budget request in the winter, and so on. A giant novelty clock in the building counts down the days until the end of the fiscal year, each year, whether Congress has done its work to appropriate money for the next one or not. Presidents, Congresses, crises, political movements – all of these come and go, but OMB’s work largely continues to cycle.

This week, OMB completed one such ritual: it released the President’s Management Agenda (PMA). The PMA–closely watched by federal employee groups, contractors, public administration academics, and the handful of general-public bureaucracy-enjoyers–is the vehicle with which each president outlines policy priorities on how the government manages itself. Each 21st-century president has had one, after George W. Bush’s Administration issued the very first one in August of 2001–and President Trump is the first to have issued two discrete ones.

Not familiar with this ritual? You’re not alone. Though not statutorily required, a PMA is meant to be a blueprint for improving how the federal government delivers policy, whether hiring, buying, designing services, listening to Americans, measuring performance, or delivering financial assistance. A PMA is also load-bearing, one of the few levers capable of coordinating action across the enormous machinery of government, aligning budgets, capacity, and accountability behind long-term modernization rather than the short-term crisis response that often drives management changes.

In a year when management issues like human capital, IT modernization, and improper payments have received greater attention from the public, examining this PMA tells us a lot about where the Administration’s policy is going to be focused through its last three years. As we did for a major policy release on hiring earlier this year, the Federation of American Scientists and the Niskanen Center are teaming up to break down and contextualize this year’s PMA.

The structure of the PMA

As OMB noted in an accompanying memo to this PMA release, the core of the PMA has for many years, been a set of cross-cutting “priority goals” that OMB is required to establish under the Government Performance and Results Act Modernization Act (GPRAMA) of 2010, which codified much of what the Bush and Obama Administrations had done to focus on performance-based goal setting and reporting. Over the years, the PMA has grown to be the organizing principle for these priority goals, explaining how they relate to one another and are part of a broader coherent whole.

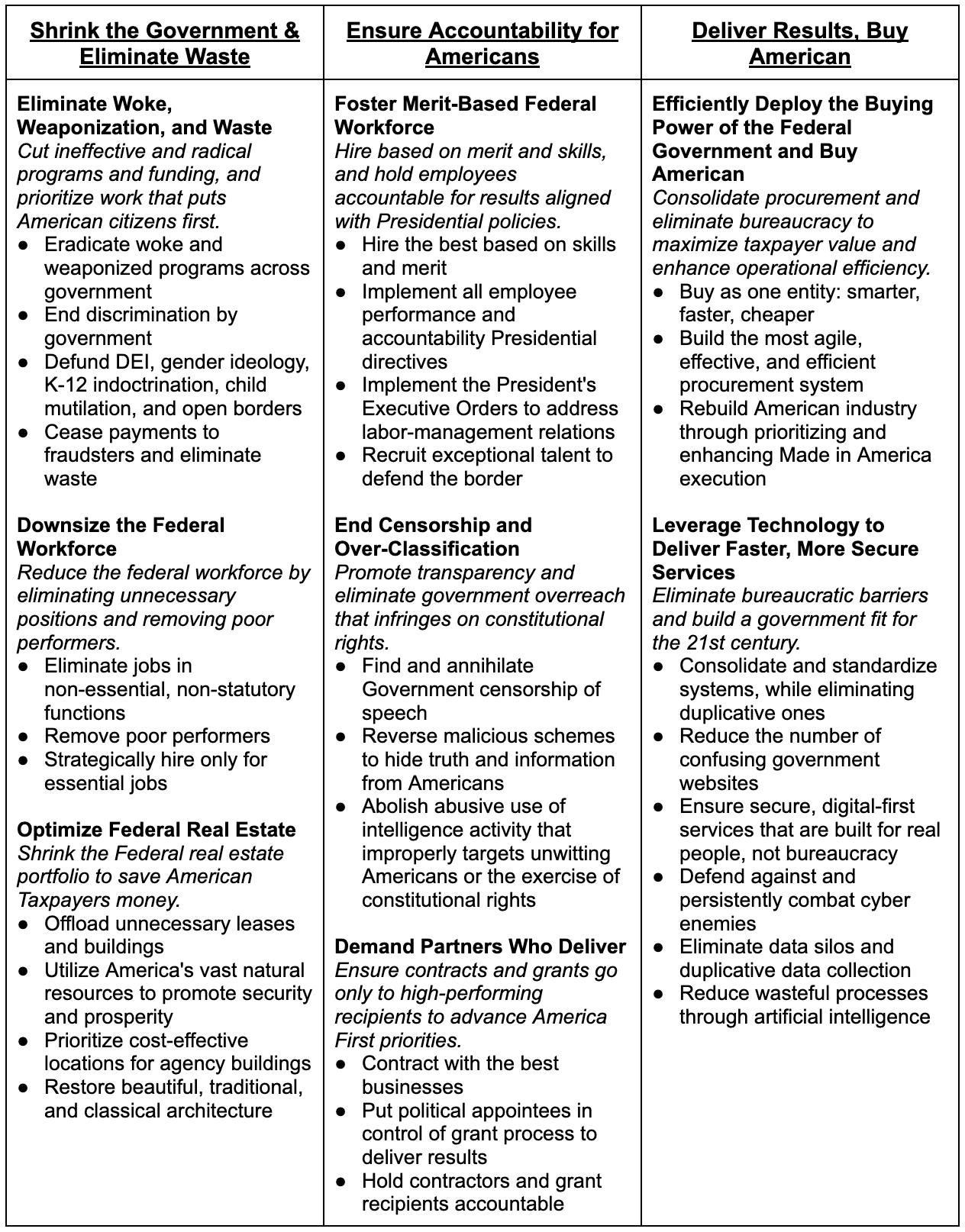

This current iteration of the PMA (reproduced below) is organized – like the Biden Administration’s was – as something of a nesting doll. It has three broad priorities, each with a few goals, and a series of objectives within each of those goals:

Unlike previous iterations of the PMA, it appears this new one won’t be accompanied by the type of long narratives and explanations typical of the Bush, Trump I, and Biden PMAs. It also differs somewhat from the Obama Administration’s approach, which focused on a series of detailed “Cross-Agency Priority (CAP) Goals that largely cohered into a formal PMA after the fact as GPRAMA was passed during the term and codified the modern process mid-stream.

Regardless of how they start, however, previous administrations have largely committed to providing ongoing reporting on their progress towards achieving each objective or goal throughout the remainder of the term. It is not yet clear whether the second Trump Administration intends to do this–Congress should inquire about their GPRAMA obligations–but in general this practice has been valuable both to keep agencies accountable for making progress and so that interested third parties can get a window into how the government is changing over time.

In the meantime, this week’s release gives us enough insight into the contours of this term’s PMA to assess how it compares with previous efforts and with what we’ve learned from observing and managing past PMAs.

What’s promising: A renewed focus on some hard problems

Normally, the PMA contains two types of initiatives. The first are evergreen topics —such as the perennial need to hire federal employees more quickly and efficiently—which have appeared in every PMA to date. The second category consists of more idiosyncratic or extremely timely “hard problems” that either haven’t received attention or where past reform has stalled. In the Biden PMA, for instance, this included integrating lessons from the pandemic’s disruption of work life. In the first Trump Administration, it included an ambitious overhaul of personnel vetting transformation on the heels of the massive OPM security clearance data breach in 2015.

Occasionally, these hard problems “graduate” out of the PMA once sustained focus produces results. The PMA’s emphasis on personnel vetting, for example, has largely given way to a multi-year, bipartisan Trusted Workforce 2.0 strategy that has and is making progress despite its challenges.

This year’s PMA includes several such issues, offering the second Trump Administration an opportunity to spotlight underappreciated but consequential aspects of federal management, including:

- Offloading unnecessary leases and buildings: Federal facilities and real estate have never truly been managed as a portfolio with all the transparency, tradeoffs, accountability and management that entails. Before the pandemic, many agencies had significant excess office space and struggled to offload unneeded square footage, even as the average age of federal facilities climbed north of 50 years old and many buildings are no longer suitable for modern work. Rationalizing and right-sizing this portfolio is a worthy and important initiative but it will be difficult: Congress has historically underfunded agencies that are aiming to reconfigure or move, and individual members of Congress frequently oppose specific office closures among their constituents. Any effort to responsibly modernize these real estate holdings will take a lot of patience and willingness to take on sacred cows, but has the potential to earn significant savings and efficiencies.

- Holding contractors and grantees accountable for performance: Most indirect federal spending flows through intermediaries and, too often, the outcomes agencies define for their work are unclear, don’t meet intent, cost more than they should, or aren’t set up for other stakeholders to learn from. Many agencies are captured technologically, intellectually, and psychologically by vendors, leading to a type of learned helplessness where their inability to technically manage contracts leads to an inability to hold them accountable for their performance. Fighting these entrenched forces and inertia is not easy, however, and will require arming agencies with the federal experts, tools and training necessary to change their approach to vendor and grantee management but also give them top-cover to push back on powerful, politically-connected awardees that fail to deliver again and again without consequence.

- Eliminating data silos: While data protections necessarily inhibit privacy and security violations, too much federal data sits in silos built by habit, culture, or old technology. Driving responsible interoperability could have a meaningful impact on service delivery, including for two of the thorniest issues in public service delivery: identity regulation and eligibility verification. However, prior actions and whistleblower complaints about misuse of personal citizen data put an imperative on the Administration demonstrating its commitment to data security under this PMA initiative. It presents an opportunity to right the ship and build the type of trust that will be required from Congress and the public to make good on the transformative power of better data management.

- Removing poor performers: The federal government has long struggled to swiftly remove poor-performing employees. The system we have today was never intended to be permanent or perfect—it was meant to provide incremental improvements toward processing removals quickly but fairly. Nearly every former deputy secretary, in administrations of both parties, has wished they could establish a simple, actionable, repeatable framework for performance management that includes reasonable safeguards. This Administration has an opportunity to chart that path. But proceeding without those safeguards—particularly protections against arbitrary or partisan dismissals—risks undermining good-faith reforms that are crucial for cross-partisan credibility and for helping managers manage well.

- Building the most agile and efficient procurement system: The Revolutionary FAR overhaul underway at OMB and the General Services Administration (GSA) is a concrete opportunity to modernize federal buying at its foundations by paring back the FAR to just its “statutory” requirements and allowing agencies to buy more flexibly. But the regulation update is at best only half the battle: the administration will need to dedicate time, people, and championship to making them stick in training, norms, culture, and leadership. It also needs to resist the temptation to add back its own non-statutory clauses, an impulse that led to the FAR’s bloated and unwieldy state in the first place.

Ideally, success in these areas means they will eventually fade into the background of standard management practice. Agency leaders may not earn themselves splashy press coverage or public adulation by improving procurement or tackling data silos. No agency head wants to spend time grappling with underutilized buildings. Genuine progress here, however, would allow future leaders to remain focused on mission delivery.

What’s returning: Places to learn from the past

This brings us to the evergreen PMA topics. To GPRA veterans, some of the things in here are expected and represent the evolution of years of work by Republicans, Democrats, and nonpartisan civil servants to make the government run better. Many of these reflect years–or even decades–of work to address some of the core challenges of managing a large organization in any sector (how to hire the right people, how to buy effectively, how to build and secure systems, etc.)

But there’s a deeper reason these issues recur, beyond aspirations for bipartisan comity. Adding an item to the management agenda is only a starting point. Meaningful progress requires far more than a talking point, executive order, or regulatory tweak. Leadership attention and cover, technical capacity to actually understand, teach, and monitor reform, oversight partnerships that orient their activities to the new model, administrative data that’s accurate, real-time, and actionable, and central funds to resource pilots too edgy to get agency support or toolkits that no one agency wants to own.

In this PMA, some of these evergreen topics include ones this Administration can learn from its predecessors and accelerate towards success, including:

- Tackling improper payments, fraud, waste, and abuse: The Trump Administration inherits a solid foundation in this area from its predecessor, which invested serious effort into tackling the surge in improper payments in the COVID-19 era. That work included investing in upfront controls, fraud prevention, and collaboration between agencies and their oversight communities. The Government Accountability Office, Agency Inspectors General, and others have also long offered suggestions about how to continue to reduce the government’s improper payments rate. Groups like the Payment Integrity Alliance are developing new technology-powered tools to support this work from outside government. These are evidence-based solutions that are likely to work, as opposed to arbitrary, highly-partisan, and ultimately untrue declarations of fraud that marked the early days of this Administration, in addition to counterproductive efforts to cut or constrain the oversight community. As OMB looks towards 2026, it should take into account these models.

- Streamlining the federal workforce and eliminating duplicative programs: While this year’s efforts are the first in a couple decades to seek to dramatically reduce the size of the federal workforce, they are not without precedence in American history. Following both World Wars (and especially through the late 1940s), the federal government had to demobilize hundreds of thousands or millions of civilian employees in a way that both treated them with dignity and economized on taxpayer dollars. More recently, in the 1990s, the Clinton Administration also conducted large-scale downsizing, with decidedly mixed results because the cuts came before changes to agency to-do lists that never materialized. It will be important for this Administration to learn lessons from the past to avoid some of the long-term damage wrought by the Clinton years, for which agencies are still paying.

- Hiring exceptional talent for key presidential priorities based on skills and merit: All presidents have priorities and many of those involve some kind of hiring surge: following 9/11, the Bush Administration had to rapidly create and staff up the Department of Homeland Security for new mission sets–for example, like airport security. More recently, the Biden Administration conducted several surges around topics like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and artificial intelligence. To make this work, previous efforts have succeeded by setting up dedicated teams that focused on specific, measurable goals and bought-in mission area leadership to champion the effort. As OMB and OPM consider their efforts this time, they should explore common data standards to ID bottlenecks, interagency approaches to share resources and talent, and investing in all the accoutrement to new and updated career paths and roles – and doing their best to embed these practices in the system, not just as part of a special effort.

They might also consider reactivating networks and programs that were successful in previous eras, like Tech to Gov, which worked across sectors to hire technologists into government. On merit and skills based hiring, implementation appears to be under way with a variety of initiatives that have promising goals, but will require significant investment of resources and leadership attention to complete, as we’ve written about.

- Buy as one entity: smarter, faster, cheaper: Successive administrations, dating back several decades, have tried to strike the right balance between decentralized and centralized procurement. The Clinton team, for example, called for greater decentralization to agencies because it “allows strangers-often thousands of miles away-to make purchasing decisions.” More recently, however, administrations have gone in the other direction, including a discrete goal to drive category management in the first Trump PMA, though agencies often still complain about being forced to use government-wide vehicles that don’t meet their exact custom needs.

To avoid the pendulum swinging back and forth between centralization and decentralization, efforts to implement this PMA should learn from efforts to achieve savings by transparent use of procurement data that were pioneered in the Biden Administration like the Procurement Co-pilot, Hi-Def initiative, and the strategic acquisition data framework. Rather than mandates from above, these initiatives help drive savings and get “spend under management” by solving information asymmetries and transparently helping agencies understand “what’s in it for them” when they use best-in-class contracts.

- Consolidate and standardize systems, while eliminating duplicative ones: The federal government has long operated on a system of both shared, government-wide, and also bespoke agency systems. The Bush, Obama, and first Trump administrations had OMB focusing on consolidating duplicative systems across government through shared services. This model, while promising in many cases, is difficult to pull off in practice – of those initiatives, the Bush Administration’s payroll consolidation is far and away the most successful, while efforts to adopt standard payment system (e.g., e- and g-invoicing) and innovative payroll solution have languished, as did GSA’s NewPay program.

This PMA should take to heart the lessons of its predecessors: agencies must be resourced up front to execute their part of any migration to shared systems, and OMB must ruthlessly prioritize and rigorously validate any requests for deviations from the standard product. In most cases, it will be far easier—and considerably cheaper—to adjust policy to fit a modern, standard solution than to customize that solution to accommodate every agency’s unique requirements.

Leaders should also address the internal politics of these transitions directly. Champions of bespoke systems often have deep attachment to their legacy tools, and their resistance can be stronger and more personal than expected.

- Defend against and persistently combat cyber enemies: Reactive and proactive cybersecurity has been a central federal government focus as long as government systems have been connected to the internet. Of all the discussed areas, continuity is perhaps most crucial to cybersecurity, with the need for sustained attention to legacy system replacement, identity management, continuous monitoring, secure architectures, and the significant talent demands that come with all of those. This Administration should heed the lessons of its predecessors, which lost valuable time to bureaucratic reshuffling and inconsistent “carrot vs. stick” approaches in its engagement with the private sector.

It’s never going to be possible to truly “solve” these issues that are core parts of ongoing management in any large enterprise. However, because progress is incremental, this PMA can accelerate its own impact by learning from what has and hasn’t worked in the past.

What’s missing: Outcomes for Americans

There is, however, one “evergreen” PMA topic that we’re surprised to see missing from this iteration: Customer Experience (CX).

The previous two PMAs featured big customer experience pushes to modernize and centralize how the government designs, delivers, and updates benefits based on customer needs. These delivered favorable results for veterans’ benefits, disaster survivors, new families, travelers and more, and fostered innovative approaches to benefits delivery like the cross-agency “life experience” program that reconceptualizes the way the government engages with people who need its support. In recent years, the bipartisan success of these initiatives has led to four straight years of improvements in the industry-standard American Consumer Satisfaction Index, with the government closing out last fiscal year at an impressive 19-year high.

While this PMA does mention “digital-first services” that are “built for real people, not bureaucracy,” that principle sits inside a technology-and-efficiency frame rather than a clear commitment to outcomes for the public. What’s missing is an explicit stance that service delivery, burden reduction, and trust-building are core measures of government performance and are not encompassed by a positive government IT experience or a more fetching website design. Plenty of core users of government services–seniors, for example–do not interface with the government in a “digital-first” way, further complicating this as a focus for customer experience.

Hopefully this absence will still allow for the bipartisan CX agenda to continue in other spaces, such as the new National Design Studio. It’s not enough to declare that the government will deliver high-quality services to the people who rely on them. Agencies need the ability to collaborate and know that the White House will back them when they need to request incremental funding to conduct user research or A/B test a new form before rolling out.

A real test of any PMA isn’t how well it modernizes, it’s whether people notice government working better on their behalf. In that way, CX is what we might call the “love language of democracy” and it’s important that OMB is attentive to building that.

What’s concerning: The culture war is coming for management

The Biden Administration received criticism for attaching progressive goals from environmental standards to equity to labor onto every possible management tool (procurement, grantmaking) until the weight of implementation is slow, diffuse, or nearly impossible. Its PMA embodied that instinct: broad, values-aligned expansive goals that had great intentions but struggled to operationalize.

The new PMA both reacts against and mirrors that instinct: it pairs standard management reforms with culture-war directives that seek single-minded discipline, accountability, and ideological alignment.

At times, it reads like two agendas stitched together: one technocratic, aimed at federal administrators, and one ideological, aimed at unofficial commissars and social media. Alongside modernization goals you might find in any PMA sit directives to:

- Eradicate woke and weaponized programs across government, which is a sweeping slogan with unclear scope at odds with the usual evidence- and performance-based mandates embedded in GPRAMA and past PMAs.

- End discrimination by government, which is a superficially unobjectionable shibboleth, but incorrectly implies that the government has been discriminating in how it carries out its management functions, despite the fact that its equity programs largely only follow the rules Congress has set out in offering employment preference to veterans or procurement preference to certain categories of small businesses.

- Defund DEI, gender ideology, K-12 indoctrination, child mutilation, and open borders, which are culture war buzzwords with no obvious relation to government performance or management issues.

And scope creeps further into territory historically outside PMA (or OMB) control, such as a set of general goals with choose-your-own-adventure interpretation and murky implementation paths, written at a strange distance from the government the Administration oversees:

- Find and annihilate government censorship of speech, which is perhaps the first time annihilate has ended up in an OMB memo and implies that there are “hidden” examples of censorship while the administration pursues overt censorship in other areas.

- Reverse malicious schemes to hide information from Americans, which gestures at a conspiratorial approach to government management that seems at odds with the Administration’s claim that it’s fully in control of the executive branch. It’s difficult to simultaneously claim that there are truths hidden from the public while also deprecating transparency, as in Federal data sets.

- Abolish abusive intelligence activity targeting unwitting Americans, which is certainly a laudable goal for any civil libertarian in a democracy but doesn’t necessarily have any resonance with normally much-duller management functions like HR and finance, which have struggled to accomplish even their overt functions in recent years, nevermind anything more nefarious.

As we’ve written before, hijacking these normally low-temperature operational processes to fight the culture war not only raises the partisan pressure on normally bipartisan issues, but it also “needlessly politicizes our institutions, snarls our civil servants in red tape, and usually fails to achieve even those unrelated objectives.”

Nowhere is this danger greater than in implementation of the PMA’s objective to “[p]ut political appointees in control of grant process to deliver results,” which supposes that political control and, by implication, alignment with the President’s partisan priorities is a main factor in how Congressionally-authorized grants are executed. The President certainly gets to set some overall parameters for grantmaking across the federal government, and politically-appointed agency heads are ultimately accountable for the money they spend.

But this priority implicates a much more arbitrary and politically-motivated process for determining how public funds are spent that strikes at the heart of what makes government action legitimate: the fair application of rules that are defined ahead of time and apply equally to all. Like a similar requirement in the Merit Hiring Plan, this also creates an obvious bottleneck in agency processes as recommendations stack up for political review, reducing efficiency and elongating the path to “results.”

Perhaps including these initiatives–which largely fall outside of the normal OMB management purview–was the price OMB had to pay to get the rest of the PMA through the hyper-partisan (even in normal order) communications processes of the White House. If that’s the case, agencies should be able to largely proceed with the rest of the agenda unbothered by also having to separately organize around these initiatives. But if not, it will be critical to ensure that directing agencies into partisan goose chases does not pull time and attention away from the harder—and ultimately more rewarding—work of genuine management reform.

Declaration is not implementation

Publicly releasing the PMA is the easy part. The real work goes into changing government. As the Bush Administration’s first PMA noted: “Government likes to begin things—to declare grand new programs and causes. But good beginnings are not the measure of success. What matters in the end is completion. Performance. Results. Not just making promises, but making good on promises.”

Many of the objectives outlined in the PMA are sound ideas with long track records across different administrations. We largely agree with many of them and they echo our policy priorities and those of partner organizations. But their appearances on multiple PMAs underscores how hard these problems are to solve. Category management,real property portfolio rationalization, and cybersecurity, were problems for many years because of the inherent difficulty of tackling them.. This is doubly true for the ideas that are fresh from the front lines of the culture war, which lack both a track record of successes and failures to learn from and the bipartisan support that more established issues—like improper payments or IT modernization—typically receive in Congress.

To actually impact the entire government – one of the largest and most complex enterprises in human history – it’s not enough to just declare that it’s the policy of the Administration that X or Y happens, or even convene regular gatherings of deputies. We’ve seen that approach fail repeatedly: agencies cannot and will not implement a PMA just because OMB issues it.

Real success requires disciplined implementation. That means selecting strategies that genuinely move the needle; setting aggressive but achievable measures and timelines; incentivizing leaders to invest time, attention, and talent in relentless follow-through; maintaining up-to-date metrics and feedback loops to know what’s working and what isn’t; and sustaining clarity of focus all the way to the finish.Without that, it becomes all too easy for OMB and agencies to skate by on superficial changes that check boxes but result in no real systems change–a PMA of performance art, where everyone claps but nothing changes. Amid all the swirl of any White House, this work of sticking the landing is the hardest part.

That’s because the PMA – like any strategy – itself isn’t really valuable on its own. It can, however, cut through the noise, clarify what the priorities are, and provide a framework for holding agencies and leaders accountable as they do their work. Any PMA will rise and fall based on how well it manages to do this. The way this term’s PMA is structured at the outset makes this task supremely difficult because it’s pulling in several directions all at once: it’s trying to simultaneously pass as a deeply partisan political document, a check-list for agencies of recent EOs, and a sober management policy agenda.

The real danger is that this lack of clarity and flurry of culture war buzzwords means nothing changes. That the same broken systems of human capital, procurement, IT modernization, security clearances, and user feedback, that have contributed to what OMB refers to as “accumulating perils” persist for yet another presidential term because OMB’s own management approach mistook a policy memo for progress and failed to chart a path forward. “Declare success and move on” is how these hard problems survive for decades.

This failure mode is easy to imagine: as humbling as it is to admit when you sit at OMB, reform requires changing the habits of work in agencies, sub-agencies, offices, and teams for whom policy memos about HR and procurement are the last thing on their mind (or even in their inbox). This is the hardest work of governance – rewiring workflows, seeding change in budgets, resetting culture – and demands management be treated as a core, can’t-fail function rather than a sideshow of dashboards and Powerpoint.

As they should be, agency implementers are more focused on the day-to-day administration of their programs: achieving their particular program objectives, responding to requests from Congress, serving the public, tracking their own budgets, and managing their own chaotic work lives. If the PMA can’t provide them with clarity, a limited number of clearly articulated goals, and a simple on/off ramp for change, it will be hard to change the direction of travel – not because of some deep state conspiracy, but because they don’t know what to focus on or how they’re going to be measured. What gets implemented, and what people experience, is what counts; everything else is decoration.

What we’re watching

As with all broad, whole-of-government strategies like this, it will only be obvious in retrospect whether this administration is successful at achieving those goals. However, there are some things to watch out for that will clue close-watchers in about how things are going:

- First, will OMB continue the type of detailed, quarterly status reports that were the hallmarks of previous PMAs and allowed the public to see how things were progressing?

- Second, are there key metrics that OMB and its partner agencies will commit to tracking, reacting to, and publishing to measure their success?

- Third, are agencies resourced to actually accomplish many of these ambitious goals and what do they prioritize (and indeed, since agencies are not mentioned in the PMA itself, what ownership do agencies feel over it)?

Finally, and more abstractly, we’re also going to be looking out for how OMB and others engage with the rest of the PMA-interested community, including career federal employees, good government groups, congressional staffers, think tanks, academics, and others who have trod this same path. The permanent institutions of the federal government don’t serve any one president exclusively; instead, they represent a deep and important investment that the American people have made in themselves as a bedrock of our democracy. While reasonable disagreements about how to do so will certainly always exist, this community can, should, and will embrace a government asking for help. OMB would do well to welcome them in.