Unlike high-income states, states with less fiscal capacity may struggle to start comprehensive paid family and medical leave (PFML) programs from scratch. States that have already established PFML — weeks of paid time off for an employee to care for a new child or a sick family member, including the employee’s own illness — are generally in the top 10 for fiscal capacity, meaning what worked for them may not apply elsewhere.

States with resource constraints should consider a more limited set of benefits and an alternative route to implementation. Namely, they could add paid parental leave, alongside a conservative amount of other leave types, to their existing unemployment insurance (UI) programs. States could minimize start-up costs by adopting existing administrative capacity and adjusting existing policy levers — state UI taxes and levels of benefit generosity — to fund and pay out parental leave benefits. Restricting the scope of paid leave benefits, rather than adding an extensive range of medical and caregiving benefits, would curb long-term costs while still helping families whose primary earners need to take time off work.

Lawmakers in Alaska have proposed legislation that could provide a proof of concept. Alaska House Bill 193 (HB193) would establish a paid parental leave program for Alaskan workers that would be managed by the state’s Department of Labor and Workforce Development. If enacted, the state would pay for the program by carving out a small share of the state’s employee-side state unemployment tax (SUTA) with benefits structured in a similar manner to the UI program.

Why Alaska’s unemployment tax can support this model

Alaska lawmakers have the opportunity to consider this approach to paid parental leave because the state’s unemployment insurance system is built on a strong foundation that has followed recommended tax practices. The state applies modest tax rates to a broad taxable wage base of $51,700 — the amount of each employee’s wages subject to the SUTA tax. The size of the wage base automatically adjusts for average state-wage growth over time. In comparison, the median wage base among states is $14,000.

The Alaskan taxable wage base has helped build up a robust state unemployment trust fund, which could allow lawmakers to establish paid parental leave without the need for any additional taxes. Entering 2025, the Alaskan UI trust fund held 2.33 times the amount of reserves needed to cover the average annual benefit cost from its most expensive three-year period. In fact, the state maintains the most solvent UI program in the country, enabling Alaskan lawmakers to apply a small portion of the UI revenue stream toward paid leave.

To understand how HB193 would adjust use of the Alaskan SUTA tax, it’s essential to understand the tax itself, including who pays it and how rates are determined. Alaska is noteworthy in that it is one of only three states that pair their federally mandated employer-side contribution with an employee-side complement.

- Employers pay between a 1% and 5.4% tax rate, based on the stability of their payrolls over the most recent three-year period; declines in payroll result in higher tax rates.

- Employees pay between a 0.5% and 1% rate on the taxable wage base. This rate depends on the average benefit costs over the most recent three-year period.

An additional solvency adjustment is applied to the employers’ SUTA obligations. This adjustment, which ranges from a 1.1% surcharge to a 0.4% credit, raises or lowers the employer-side tax based on the reserve levels in the UI trust fund.

To cover the cost of the paid-leave provisions, the sponsors of HB193 include two unemployment tax reforms. A portion of the employee-side and the employer-side SUTA contributions would each be used to fund the paid leave program, albeit to varying degrees.

The employee-side SUTA tax would primarily cover the cost of parental leave benefits. Alaska’s Labor Department would begin collecting a 0.15 percentage point share of the SUTA tax paid by employees and depositing it in the newly established paid leave fund account. This employee contribution would be offset by a uniform 0.15 percentage point reduction in the employee SUTA tax deposited into the state UI trust fund. In short, employees would not see a tax increase.

Meanwhile, a portion of the employer-side SUTA contributions would only be applied if the department determines it is necessary to maintain program solvency. Under this scenario, Alaskan employers would make a “special” contribution to the paid leave fund that equals 0.20 percentage point share of their SUTA tax rate, and direct an additional 0.10 percentage point share to an account for employment assistance and training. Employers would be able to offset these contributions by paying an identical amount less in SUTA taxes to the UI trust fund. However, under HB193, the UI tax rate for any individual employer cannot be reduced below 0.5% after factoring in these special contributions.

How HB193 would structure benefit access and payments

Under the bill, lawmakers would open up paid parental leave access in 2027 to Alaskans when they become new parents via birth or adoption, have a child placed in their custody, or become appointed as a child’s legal guardian. While these scenarios differ from the usual reasons workers apply for unemployment benefits, they lead to the same result: temporary time out of work. HB193 treats these jobless periods in a similar manner. The minimum earnings requirements, the benefit sizes, and the benefit durations for Alaskan paid parental leave would largely mirror that of the state unemployment insurance system.

Right now, Alaskans must meet select monetary criteria to qualify for unemployment benefits. Alaskans must earn $2,500 in either the first four of the most recent five completed calendar quarters (referred to as the regular base period) or during the most recent four completed calendar quarters (known as the alternative base period). It’s also necessary to have earned wages in multiple calendar quarters during this period. Alaskans would need to meet these same requirements to qualify for paid leave under HB193.

The paid leave benefits provided to qualifying Alaskans would correspond with the size of weekly UI payments. Furthermore, HB193 would make additional reforms to help eliminate a middle-class income penalty present in the existing benefit structure. Since 2009, the Alaskan legislature has kept the maximum weekly UI benefit for individuals capped at $370. Adjusting for inflation, the cap has resulted in a 35% reduction in the value of the maximum weekly amount. This stagnation has effectively penalized middle-class Alaskan workers. Median wage workers in Alaska receive a weekly UI benefit that is now only 25% of their prior wages, while a minimum wage Alaskan worker has 49% of their prior wages replaced.

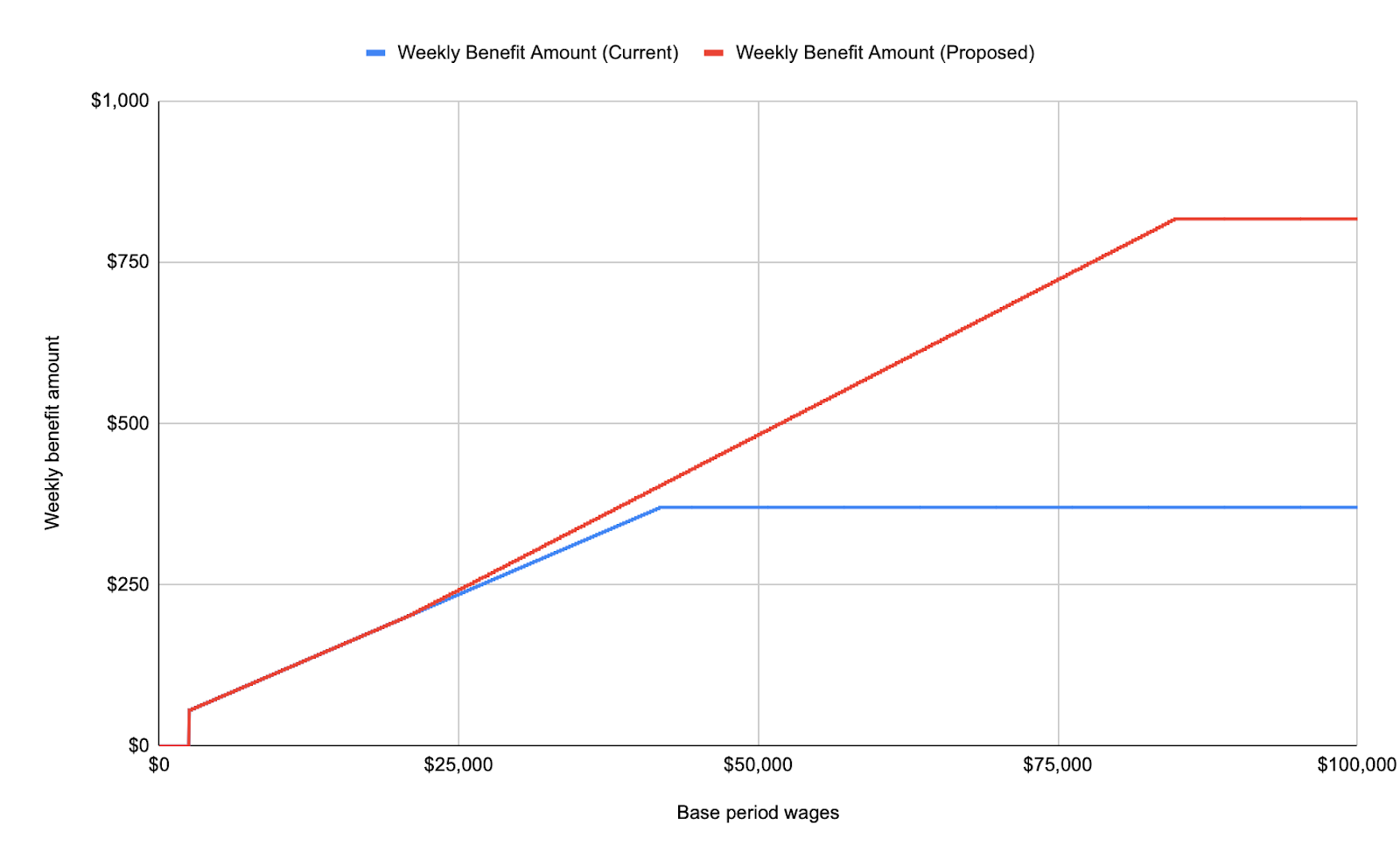

HB193 would fix this penalty by lifting the maximum weekly benefit amount for both programs to $817. This update would help ensure that middle-class workers receive paid leave or UI benefits equal to half of their normal wage rate. As seen in the figure below, the benefit changes would primarily support Alaskans earning over $40,000 per year. Under HB193, a median wage Alaskan worker would receive a $728 weekly benefit amount compared to the current amount of $370 per week.

Figure 1: Current weekly benefit amounts and proposed levels under Alaska House Bill 193

Although there are similarities, HB193 would differentiate the duration of paid leave benefits from the current UI program in a couple of ways. Alaskans can qualify for 16 to 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, depending on the amount of wages earned in the base period and the distribution of those earnings across those calendar quarters. Under HB193, Alaskans could receive a minimum of eight weeks of paid leave benefits. The maximum number of benefit weeks of paid leave can go up to 26, but may be lower depending on fund solvency issues or department forecasts.

Taken together, these provisions offer a way to integrate paid parental leave into Alaska’s UI system. Still, a few policy levers warrant closer attention while lawmakers continue to refine HB193. For one, a fiscally cautious approach might moderate the scope of the proposed fixes to the middle-class benefit penalty. Establishing fairer wage replacement for middle-income workers is unquestionably worthwhile, but it can be expensive. Lawmakers should evaluate actuarial projections carefully.

Second, lawmakers might want to offer a more uniform amount of paid leave to eligible parents. Under Alaska’s UI system, the number of benefit weeks depends on a worker’s earnings and the distribution of those wages across the base period. Alaskans with lower or more variable incomes often qualify for significantly fewer benefit weeks. That design may be ill-suited for paid parental leave, where new parents—regardless of income—often require a set period of time to recover and bond with their new child. Lastly, lawmakers could consider incorporating a small number of weeks of paid medical leave into the legislation.

Conclusion

House Bill 193 offers a pragmatic path toward establishing paid parental leave in Alaska. By leveraging the existing administrative and fiscal infrastructure of the unemployment insurance system, lawmakers could extend paid leave benefits to new parents without raising new taxes or creating a separate bureaucracy.

If implemented carefully — with attention to benefit levels, duration, and long-term solvency — HB193 could serve as a national model for states to deliver on paid leave, especially those with more limited fiscal capacity. The proposal demonstrates how greater economic security for working families doesn’t always require creating new government systems—it can be achieved by modernizing and expanding the systems already in place.