State unemployment benefits can be a lifeline after a layoff, especially for low-income workers already struggling to make ends meet. Yet states’ eligibility rules can make it harder for them to qualify for benefits than it is for their higher-income counterparts. States can fix this problem with a simple reform.

Most states assess workers according to monetary eligibility standards to determine whether individuals qualify for support. This standard is generally a mandatory level of earnings in recent calendar quarters.

The penalty on low-income workers stems from state use of earnings requirements. In those states, workers with lower wages must work more hours than higher-wage earners in order to qualify. Two states — Washington and Oregon — offer an alternative: an hours-based standard regardless of income. States with an earnings-based system could consider shifting to a uniform requirement to eliminate the low-income penalty in their UI programs.

Measuring penalties in monetary eligibility requirements

When determining unemployment insurance eligibility and benefit amount, state unemployment agencies review claimants’ quarterly UI wage records that are periodically submitted by employers. UI agencies evaluate wages earned during the “base period” — usually the first four of the five most recently completed calendar quarters before the unemployment claim – for claimants to be approved for benefits. Most states can also determine eligibility according to earnings in the most recent four completed quarters.

The minimum earnings requirements are typically a fixed dollar amount, which varies greatly across states. While the average state earnings requirement is $2,965 during the base period, it ranges from $130 in Hawaii to $8,103 in Arizona. States may attach additional criteria, such as making it necessary for workers to earn income in a certain number of calendar quarters of the base period.

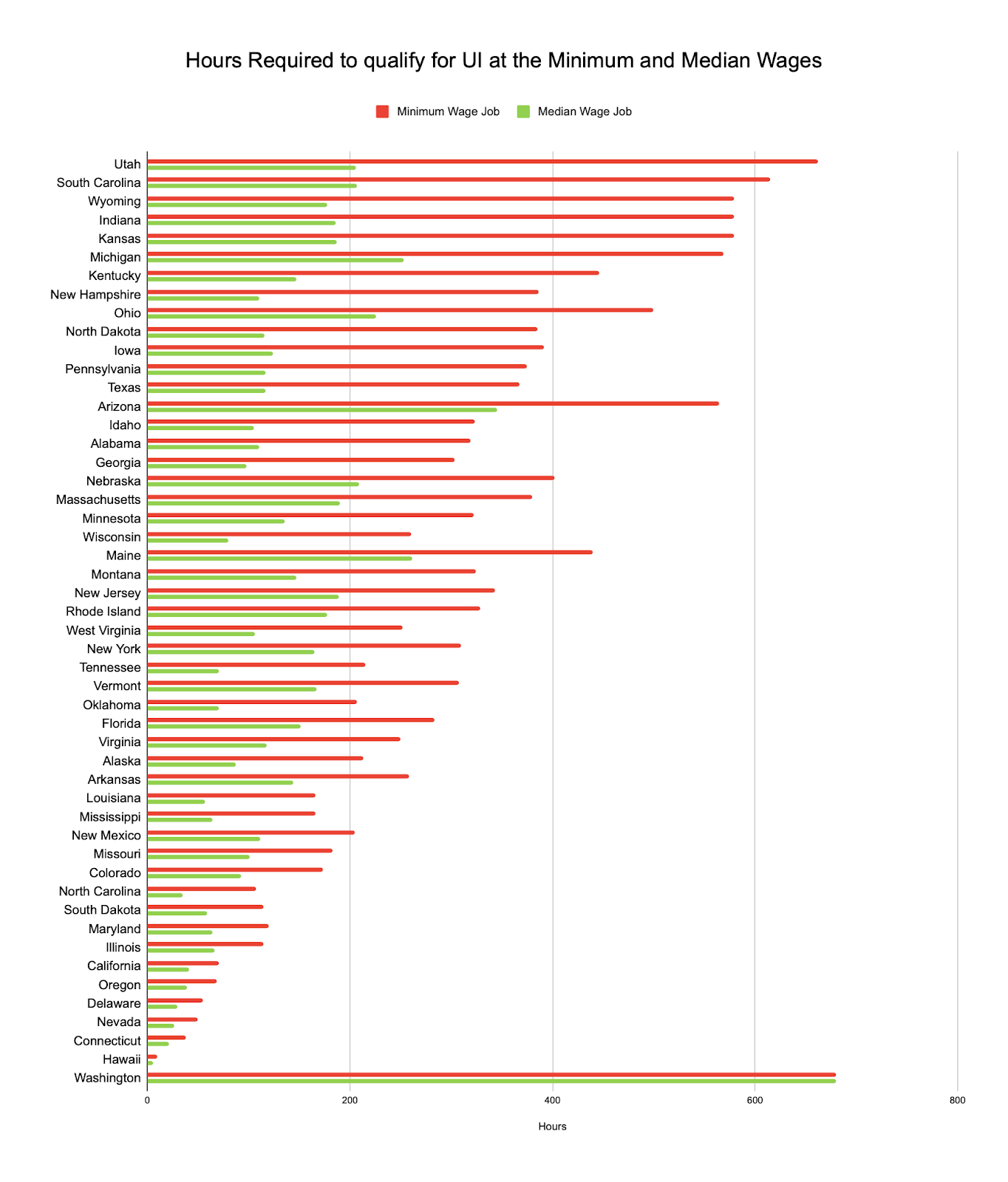

To understand the low-income penalty across states, consider two hypothetical workers: one working at a state’s minimum wage and one working at its median wage. The penalty is the difference between the number of hours required of the minimum wage workers and the median wage workers in a state.

As seen below, the magnitude of the low-income penalty depends on a state’s earnings requirements, minimum wage, and median wage. Among states with an earnings requirement, Hawaii has the smallest low-income penalty: an individual earning the minimum wage must work 4.21 hours more than a median wage worker to qualify for UI. Conversely, Utah, with the largest penalty, requires a minimum wage worker to put in 457 more hours than a median wage worker.

In all, 23 states require minimum wage workers to log an additional 160 hours — a month or more of full-time work — than median wage workers to qualify for UI benefits.

Source(s): Wage data from the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics program. Note: States assorted according to the size of penalty.

Washington and Oregon are the only states that base eligibility for unemployment benefits at least in part, on hours worked. In Washington, unemployed workers only qualify if they put in 680 hours during the base period. This hours threshold guarantees that workers of all income levels qualify for the same amount of work effort, albeit that the 680-hour minimum is a higher eligibility standard than in any other state. Oregon applies an earnings minimum, with the potential to assess hours as an alternative if workers request what the state calls an “Amended Monetary Determination.” Minimum-wage claimants in Oregon generally face a low-income penalty of 30 hours.

States can standardize their criteria

By implementing a uniform hours threshold, states can remove the low-income penalty and allow low-wage workers to work the same number of labor hours as median wage workers to qualify. There are several options available. States could opt for an hours threshold that is either: unrelated to the existing earnings requirements, equal to the number of hours that minimum wage workers currently need to qualify, or equal to the number of hours that median wage workers need to qualify now.

If states opted for a high hours threshold like Washington, it could increase the net burden on workers. Some middle-class workers who qualify for benefits through existing earnings requirements would no longer be eligible with a high hours requirement. Fairness among workers would increase but access would decrease. In contrast, switching from an earnings minimum to an hours threshold could improve accessibility and equity for low-income workers.

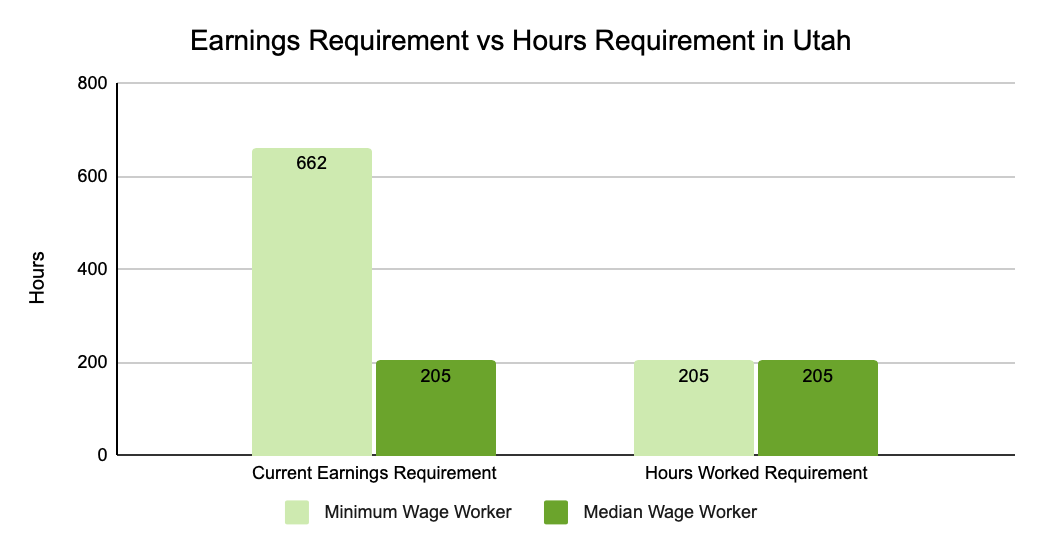

For example, Utah could convert its base-period earnings minimum of $4,800 to an hours minimum of 205 hours, the amount of work hours for a median-wage worker to meet the state’s current earnings threshold. This reform would allow minimum-wage earners to work the same amount of time to qualify for UI, rather than hundreds of hours more.

Conclusion: Equal access for equal work

States can remove a burdensome penalty placed on low-wage workers by changing their earnings requirements for UI benefits to an hours-based standard. If states applied a more uniform hours requirement, the penalty on low-wage workers when accessing benefits could be greatly reduced. However, the overall size of the hours-based requirement will determine how much more accessible the program would actually be.