Economic growth is sure to be at the center of the coming debate over tax reform. The goal posts have been set. To quote the official White House web site,

To get the economy back on track, President Trump has outlined a bold plan to create 25 million new American jobs in the next decade and return to 4 percent annual economic growth.

The “unified framework” for tax reform endorsed by Congressional Republicans echoes this, promising to “create jobs at home and fuel unprecedented economic growth.”

How realistic is the goal of 4 percent real GDP growth, or even the 3 percent cited by some of the more cautious members of the administration? The answer depends, in part, on the kind of tax reform we get, and on how tax cuts affect productivity, neither of which can we know at this early stage in the process. This post will leave those topics to others, and focus, instead, on some demographic trends, no less important for future growth, that we already know with a fair degree of certainty.

Demographic tailwinds of the past

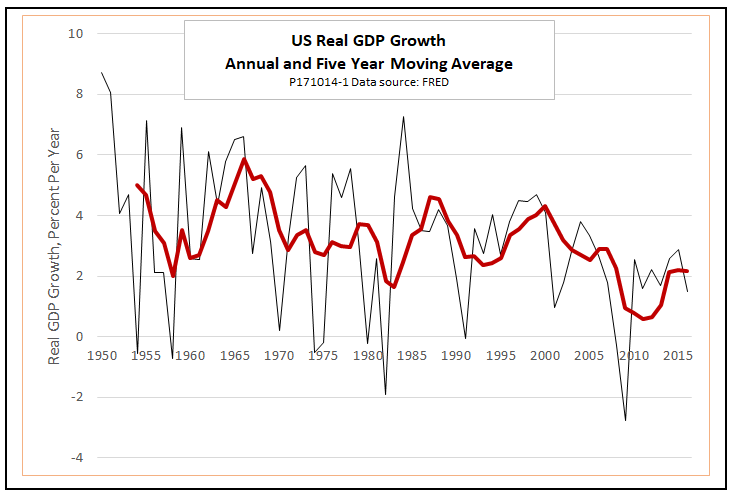

Real GDP growth of 4 percent per year would not actually be unprecedented. We have been there before. As the following chart shows, the five-year average of U.S. real GDP growth exceeded four percent per year several times in the post-World War II period. The most recent such episode ended with the brief recession of 2001. The average growth rate for the entire period from 1950 to 2000 was 3.7 percent. Since then, however, the economy has yet to produce sustained growth of even 3 percent. What has changed?

It turns out that the high growth rates of the post-war period were fueled, in large part, by three big demographic tailwinds: Population growth, growing labor force participation by women, and a low dependency ratio. Let’s look at some data.

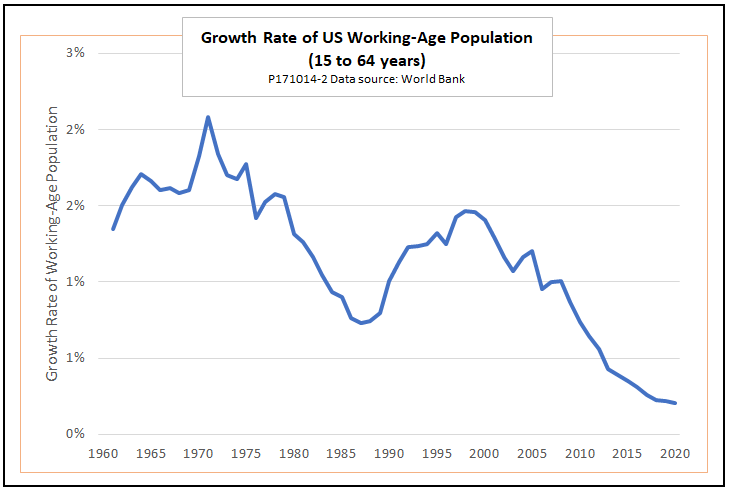

The next chart shows the growth rate of the U.S. working-age population. It peaked at over 2 percent per year in 1971, as the largest cohort of baby boomers entered the labor force. It peaked again, but less sharply, in 1998, as their children reached working age. Since then, it has been on a downward trend. In short, throughout most of the post-war period, expansion of the working-age population contributed from one to two more percentage points to economic growth than it does now, or will do at any time in the foreseeable future.

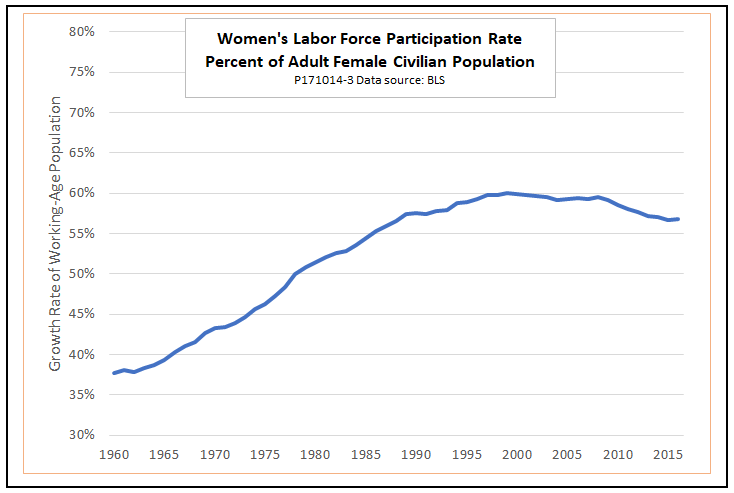

Over the same period, as the next chart shows, labor force participation by women also increased, from 38 percent in 1960 to a peak of 60 percent in 1999. Since women constitute roughly half of the working-age population, the increase in the labor-force participation rate added about 11 percentage points to the labor-force participation rate as a whole. Even if the total working-age population had remained unchanged, rising labor participation by women would by itself have added more than two-tenths of a percentage point to economic growth.

A comparison of the two preceding charts reveals a fortunate coincidence. The fastest increase in women’s labor force participation took place from the 1970s through the mid-1980s, just as the coming-of-age of the last baby boomers was producing a dip in the rate of growth of the working age population as a whole. By the late 1980s, when women’s participation rates neared their peak, the arrival of the boomers’ children brought an upturn in growth of the working age population. Working together, then, these two factors helped to maintain steady growth of the labor force throughout the last four decades of the twentieth century.

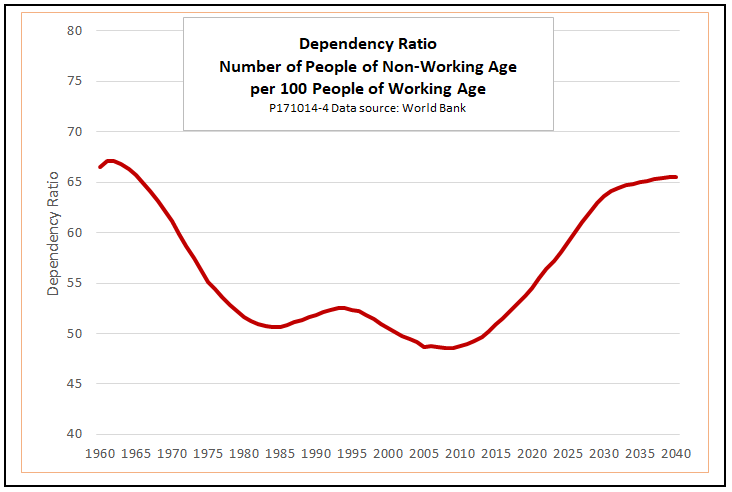

The third growth-friendly demographic trend of that period was a low dependency ratio; that is, a relatively low number of children and seniors per 100 people of working age. As any country makes the transition from a situation of high birth and death rates to one of lower birth rates and longer life expectancy, the dependency ratio will fall. As the last large generation of children enters the labor force, it hits a sweet spot. As that generation begins to retire, and lives longer in retirement, the dependency ratio rises again. In the United States, the sweet spot lasted from roughly 1980 to 2010. By 2040, the U.S. dependency ratio is expected to be close once more to its level of 1960.

A low dependency ratio is favorable to growth in three ways. First, it increases labor force participation, since fewer people of working age find it necessary to quit their jobs or cut back on hours to care for children or elderly parents. Second, it boosts the average saving rate, since people earn more than they consume during working years, and consume more than they earn in childhood and in retirement. Third, for any given level of total output produced by people of working age, output per capita is higher when the dependency ratio is lower. Although discussions of economic growth in the context of tax reform often focus on growth of total GDP, it is GDP per capita that determines how well people actually live.

Twenty-first century demographic headwinds

As the preceding charts show, all of the demographic tailwinds that boosted growth between 1960 and 2000 have now turned into headwinds. Population growth is approaching zero. Women’s labor force participation, while still high by historical standards, has fallen a bit from its peak. The dependency ratio is rising, and will continue to rise. These factors will continue to depress growth in the future, even if tax reform and other policy changes manage to restore the productivity gains that were seen in high-growth periods of the past.

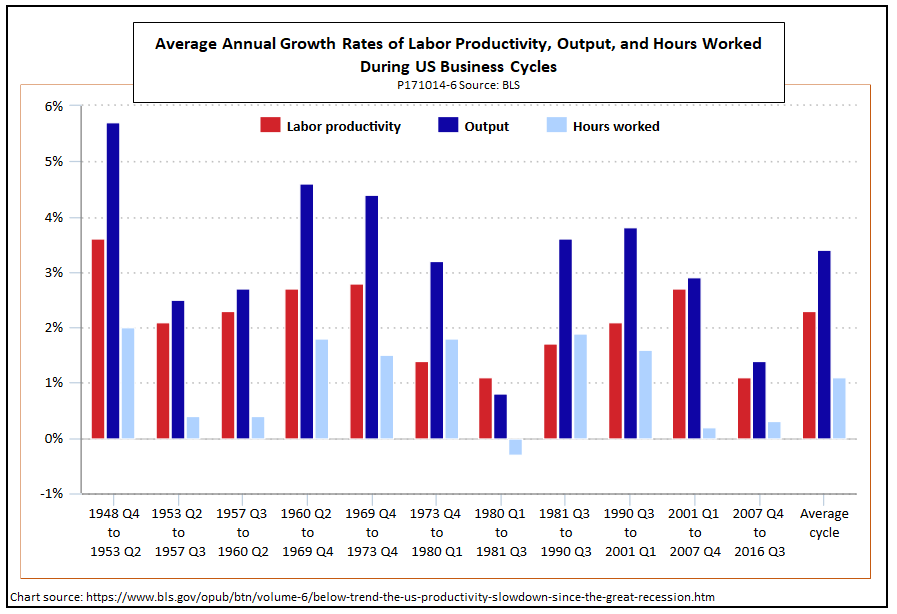

The following chart from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows one way to view the depressing effects of these demographic headwinds. The bars represent annual average growth rates of labor productivity, output, and hours worked for each business cycle from 1948 to the present. Over five complete business cycles from 1960 to 2001 (omitting the anomalous mini-cycle of 1980-81), output growth averaged 3.9 percent. Of that, growth of labor inputs contributed about 1.7 percentage points and growth of productivity about 2.2 percentage points. The most recent cycle, although still incomplete, has so far produced output growth of just 1.4 percent. Productivity growth has averaged 1.1 percent, half of the 1960-2001 average. Labor inputs have grown by just 0.3 percent, or 1.4 percent below the earlier average.

What we see, then, is that even if tax reform and other policy changes were to restore productivity growth to its average rate of 1960-2001, demographic headwinds would still limit growth of GDP to about 2.5 percent per year, at best. Even if productivity growth hit the above-average rate of 2.7 percent recorded from 2001 to 2007, real GDP growth would still fall short of 3 percent.

One more headwind: Immigration policy

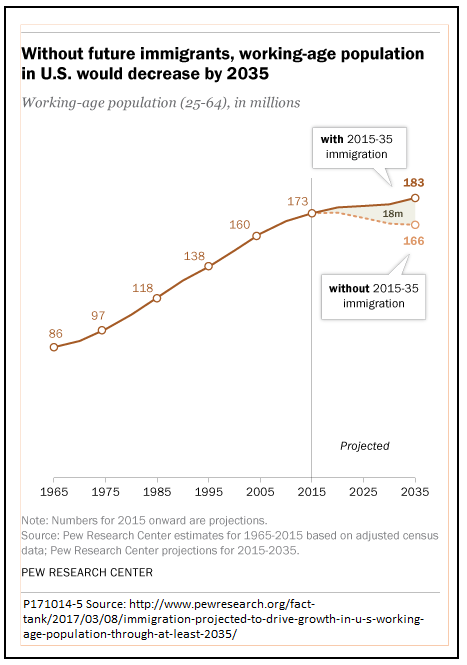

Even these estimates may turn out to be too optimistic, since they do not consider possible changes in immigration policy. Until recently, forecasters have assumed that immigration will continue to significantly bolster the growth of the U.S. working-age population. The next chart, taken from a study by the Pew Research Center, shows that with unchanged immigration policy, the U.S. working-age population would grow by almost 6 percent from 2015 to 2035. Without immigration, it would fall by almost 4 percent. (These numbers include both legal and illegal immigrants.)

In addition to expanding the labor force, immigration also has a favorable effect on the dependency ratio. Our earlier chart showed the dependency ratio rising from 50 dependents per 100 people of working age in 2015 to 65 in 2035. Without immigration, the dependency ratio will rise much faster, since the ratios for immigrants are far below those for the native population. Available data suggest that the dependency ratio for legal immigrants is around 35. For illegal immigrants, it appears to be lower still, perhaps no higher than 20.

This is not the place for a general discussion of the merits of immigration, but whether we like it or not, the Trump administration is bringing sharp changes to policy. Illegal immigration is already slowing, as another Pew study documents. Proposed policy changes are likely to restrict the inflow of legal immigrants, too. Together, they promise a future in which growth of the working-age population turns negative while the dependency ratio rises at an increasing rate. In this regard, the administration’s policies—promoting growth with tax cuts while simultaneously restricting immigration—are inconsistent.

Why it matters for tax policy

These demographic considerations matter for tax reform, for two reasons.

First, in the name of economic growth, we will be asked to do things that we would otherwise find disagreeable. We will be asked to give large tax breaks to “job creators,” knowing full well that the benefits will be shared among all high-net-worth individuals regardless of whether they have ever created a job or not. We will be asked to end estate taxes in the name of saving small businesses and family farms, even though the Tax Policy Center estimates that such businesses account for only fifteen hundredths of 1 percent of all estate tax revenue. We will be asked to cut rates on pass-through businesses so that wealthy lawyers and doctors can pay less than middle-income wage and salary earners.

If we were sure these actions would bring higher growth, some of us might hold our noses and accede to them. If the promised growth does not materialize, we will feel that we were swindled.

Second, we will be asked to forget about real tax reform and settle for simple tax cuts, on the theory that the resulting growth will allow the cuts to pay for themselves. If they do not, we will end up with a much larger deficit. Maybe you are among those who think that deficits don’t matter, but not everyone in Congress thinks that way. Rising deficits will surely bring pressure to cut spending on infrastructure and social programs.

As I pointed out in a previous post, the United States already does a poor job of converting raw GDP into the things that really matter for social prosperity—health, education, environmental quality, and personal security. The deal we are offered in the unified framework would represent a bad tradeoff between GDP and social prosperity even if it fully delivered on its promises for growth. If demographic realities put the growth targets out of reach from the start, the bad tradeoff becomes a terrible one.

It is not that economic growth is bad in itself. It is not that we don’t need real tax reform that would cut top rates and close loopholes. What does look bad, though, is a package of unfunded tax cuts, with benefits concentrated on high earners, followed by disappointing economic performance and cuts to spending on infrastructure, health, education, and income security. That is what we are at risk of getting as the “unified framework” winds its way through Congress.