This paper is an update to an unpublished report written for New York University’s Marron Institute of Urban Management, with support from Stand Together. The original version was coauthored with the late Mark Kleiman.

Introduction

Advances in information and communication technology now allow officials to track individual behavior with far greater accuracy, which is enormously valuable in community corrections. In particular, those advances ought to enable social control using less intense sanctions and rewards, because swiftness and certainty of response can substitute for the severity of sanctions or generosity of rewards. If the perceived increase in intrusiveness is offset by a lower level of unfairness and harshness, the resulting improvement in perceived legitimacy and procedural justice (in the eyes of the population being supervised) will also tend to improve compliance.

The management of people under criminal justice supervision is one attractive target for the high-certainty/low-severity approach. Implemented well, it could curb re-offending and incarceration while helping people with criminal histories re-integrate into mainstream society.

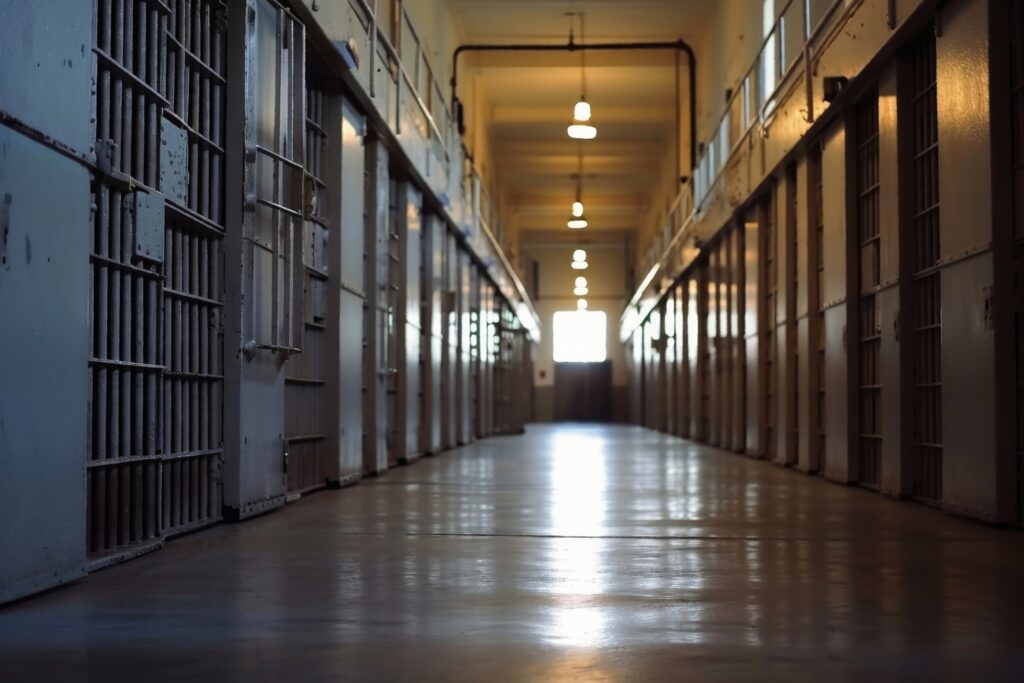

Only a couple of centuries ago, crime was often dealt with by revenge from the victim or their family, or by fines, forced labor, corporal or capital punishment, or exile. In the early 19th century, confinement became the default penalty. Despite dramatic changes in technology that have reshaped most other aspects of commerce and government confinement remains the dominant response to crime today.

Some people currently behind bars pose little threat to public safety, but that alone will not justify their release unless alternative measures can serve the goals of incapacitation, deterrence, retribution, and rehabilitation. Today’s community-corrections system rarely achieves those goals. Because judges and prosecutors are understandably reluctant to see criminals avoid punishment, probation often includes terms that are intentionally onerous. The result is a maze of poorly designed rules, enforced more or less arbitrarily, with scant capacity to redirect clients toward lawful lives or incapacitate them to prevent additional offending. Saddling probationers—most of them poor—with the costs of their own supervision only deepens the damage.

The over-use of confinement is therefore unsurprising. Countless marginal decisions leaning towards over-incarceration—decisions that seem reasonable to the individuals making them—have resulted in a national incarceration pattern that makes the present drastically different from the historical record and the U.S. an outlier internationally. Keeping nearly two million people behind bars in prisons and jails at any one time—five times the U.S. historical norm and four times the level of Western Europe—seems hard to justify, especially after a quarter-century of declining crime rates. In light of the federal government’s recent decision to reduce public safety funding, states may find it increasingly unaffordable to sustain these levels.

The challenge, then, is to create non-confinement options that are more restrictive than community corrections as currently practiced, but less punitive, expensive, and destructive than a cell. Affordable, highly-reliable electronic location monitoring could make this middle-ground option possible. That is not to say that everyone under community supervision, or even everyone now behind bars, requires that sort of enhanced community supervision; many would do fine unsupervised or only lightly supervised. However, it seems likely that the intelligent application of electronic position monitoring capacity could contribute to a significant shift from confinement while preserving, or perhaps even improving, public safety.

Electronic position monitoring

Electronic position monitoring technology has existed for decades. But its application suffers from both technological and process problems, and consequently it remains under-utilized compared both to confinement and routine community corrections.

Many of those technological hurdles are now being overcome thanks to advances in miniaturization and information technology. Pairing today’s superior technology with improved program design could significantly expand the reach of monitoring, reducing crime, incarceration, and costs while enhancing the life prospects of people under supervision.

Crucially, electronic monitoring is not a stand-alone “program.” An ankle bracelet is just a tool; on its own it does not deter, incapacitate, or rehabilitate. The real question is whether we can develop programs that use electronic monitoring to enforce clear and coherent rules, enforced with the swift, certain, and fair responses that drive compliance.

Early evidence suggests we can—at least for a sizable population of supervisees—perhaps hundreds of thousands, or even millions. Confirming that promise will require rigorous field trials that test how well these redesigned monitoring programs deliver on public safety goals while offering a humane, cost-effective alternative to incarceration.

The logic of electronic monitoring

The value of electronic monitoring lies not in the ankle bracelet itself, or even the data it gathers, but in the system built around it. A program must decide how to receive, interpret, and act on the location data; otherwise, the technology is wasted. Debating whether “EM” is useful in the abstract—or even arguing over technical specs outside the context of the programs employing them—misses the point.

The right questions to ask are:

- How many people now behind bars could be safely released if they could be tracked?

- How many people already in the community would pose less danger to others—and face lower incarceration risk—if monitoring were added to their supervision?

An optimal system for today’s United States would likely have many fewer people in jail and prison and fewer under active community-corrections supervision—but a much larger fraction of those who remain under supervision backed by clear rules would wear monitors.

Electronic monitoring today

EM was first used in the U.S. criminal justice system in 1983. Today, there are approximately 250,000 units in use, of which around 100,000 are GPS-enabled, among roughly 5 million people under correctional supervision: 3.7 million are under probation or parole supervision in the community, and 2.2 million are behind bars. (At any one time, many more are out on pretrial release, with or without money bail; a large share of those in jail are awaiting trial.) The implied community-corrections usage rate of 5% (250K/5M) is misleading; since EM is heavily used for sex offenders, the rate among violent, property, drug, weapons, and public-order offenders must be much lower than 4%.

The market for EM equipment is estimated to represent $400M of sales domestically per year. This implies an average daily cost of equipment of $5 per offender (anecdotally $3-8) or $1,800 per unit per year. That’s somewhere between the roughly $1000/year total average cost of probation supervision and the $3000/year average for parole, and a tiny fraction of the estimated $30,000/year for a prison or jail cell. While these figures reflect average costs, the marginal cost of monitoring one additional person is often much lower—especially once the system is in place.

There are approximately a dozen firms in the EM market, selling mildly differentiated equipment. The market leaders are BI (owned by Geo Group), 3M, STOP (owned by Securus), and OmniLink. The price range primarily depends on the level of technology in the device, the frequency with which it collects data and reports to the network, and the number of devices purchased by the agency.

The entry-level equipment—now nearing obsolescence—is a tamper-proof, cellular-enabled ankle bracelet that pairs via radio frequency with a physical hub located in the client’s home. The tamper-proofing methodologies are unique to each device—and kept highly confidential for proprietary as well as security reasons—but achieve the goal of creating a notification if the bracelet is removed. The radio frequency pairing is programmed to know when the bracelet should be within range of the hub (corresponding to being inside the home for curfew). The hub features a motion sensor inside to prevent it from being moved by the client, is plugged into an outlet, and the bracelet is powered with a rechargeable battery. If the bracelet or hub is tampered with or if the subject moves outside the permitted range, a cellular signal transmits an alert to the network.

Since the early 2000s, ankle monitors have incorporated GPS, letting supervisors track a person’s exact location rather than merely whether they are near a home-based hub. Newer models go further, combining GPS with cell-tower triangulation and Wi-Fi signals for greater precision and reliability. These advances enable more detailed rule-making regarding where a monitored individual is and is not permitted to go.

Many kinds of agencies—federal, state, and local—run electronic-monitoring programs through courts, pre-trial services, probation and parole departments, corrections, police, and immigration offices. Most lease the hardware (and sometimes the monitoring service) through competitive contracts that charge a set daily rate.

That cost is usually passed on to the wearer, creating a heavy burden for people who are often already indigent. Some jurisdictions offer limited assistance funds, but the help is uneven. A better approach would be to cut or eliminate user fees—either by lowering overall costs (for example, replacing ankle bracelets with smartphone-based apps where appropriate) or by covering the expense in public budgets, savings made possible if EM reduces reliance on jail and prison beds.

Once the equipment is deployed in the field, agencies need a way to collect, triage, process, and respond to the data that the devices are producing, and in particular to indications that the subject is either violating the movement constraints imposed by the terms of his supervision or has removed or disabled the EM device. Agencies need to decide which data merely get stored, which create notifications, and how to act on those notifications, either at once or at a later time, and which should be routinely checked. Systems geared toward immediate response (frequent for sex offenders) are referred to as “active monitoring,” and cost more than systems geared toward simply notifying the client’s supervisor for later action (“passive monitoring”). In either case, there needs to be a process for triaging and then dealing with urgent alerts.

The software provided by contractors along with the hardware has a wide range of capabilities: registration of new clients; creation of rules about curfews, inclusion zones, exclusion zones, and more; and to decide what actions constitute an alert and what the form of that alert is (texts, email, or phone call).

Agencies handle electronic-monitoring alerts through a mix of models. In some jurisdictions, the supervising officer is the sole recipient and responder of every alert for each person on their caseload. Others create internal triage mechanisms, such as call centers, and others outsource some or nearly all the work to private companies. Still others run their own supervision during business hours and outsource coverage for evenings and weekends. The cost of outsourcing supervision varies with contract size, hours of coverage, and the alert strictness of the triage protocol, but it typically ranges from about $10 to $15 per participant per day.

Legacy problems: Real and perceived

EM still falls short of its potential to meaningfully reduce reliance on incarceration. Persistent barriers—technical glitches, equipment costs, staffing demands, and civil liberties concerns—limit wider use. Yet many reservations stem from outdated experience with bulkier, less reliable devices; the gap between perception and current reality is often wider than critics assume. Ongoing advances in hardware, lower prices, and a developing body of best practices could soon make monitoring a viable alternative to confinement.

EM, especially active monitoring, can create significantly more work for supervisory officers, who are already stretched beyond practical limitations. Ironically, EM can increase—rather than lighten—staff workloads. Legacy devices often inundate officers with an overwhelming number of alerts, most of which stem from technical issues, rather than actual violations. For example:

- An Indiana GPS program reports having received 1,100 alerts in a month in a group of 325 offenders, with only 10 of those alerts actually leading to enforced violations.

- In Tennessee, a sample of 68 GPS offenders found that officers failed to clear 80% of 11,347 alerts generated over 10 months, including alerts for leaving home after curfew or entering exclusion zones. “Clear” means to respond to an alert generated by the system, either by confirming that it is a false alert or sanctioning the client as necessary for breaking a rule.

- An AP investigation revealed that 21 agencies logged 256,000 alarms for 26,000 offenders for one month.

- The same investigation showed that 230 parole officers with the Texas DOC handled 944 alerts per day in one month (4 per officer per day); that 31 field officers in Delaware handled 514 alarms per day (17 per officer per day); and that 212 officers in Colorado handle an average of 15,000 alerts per month (2 per officer per day). In some states investigated, agencies only responded to alerts during regular business hours.

- In our own informal test of several competing EM systems, there are repeated instances where the system generated an alert when the person wearing the anklet was asleep in bed.

Most false alerts stem from “satellite drift,” which occurs when GPS signals are momentarily lost due to interference from tall buildings, underground structures, or large bodies of water. For example, a person might walk into a large building where they are mandated to be for work, but a confused GPS-enabled EM device might say they are five blocks away, causing an alert. Another common cause of false alerts is lost signal. When somebody walks into a large building where they are mandated to be for work, a confused GPS-enabled EM device might say they are five blocks away, causing an alert.

If the devices produce an unmanageable number of alerts, agencies have two choices: ignore them (which renders the devices useless) or invest in a system of triage, which adds significant cost. Some departments triage by creating internal call centers, while others outsource to private companies (usually the equipment provider). These centers might use common sense to ignore an alert or may call a client to investigate; either way, this means only serious, already-investigated alerts reach officers. But this approach meaningfully increases the costs of EM, which makes it a less attractive alternative to incarceration.

Because agencies often fail to act promptly on electronic monitoring alerts, the technology seems ill-suited for people who pose significant public safety risks. Even if EM would offer better protection than traditional probation or parole—a modest benchmark—the risk that a monitored individual will commit a serious crime after an alert is ignored can become intolerably high for a certain set of high-risk offenders. That makes the use of EM in those cases a poor competitor with incarceration, both in the view of judges and in the view of community-corrections managers.

Several high-profile failures have reinforced these fears. For example, in 2013, a Colorado parolee removed his ankle monitor and, within five days, murdered two people—including the state’s corrections chief. The supervising agency did not respond to the alert until hours before the second killing. More broadly, between 1989 and 2009, there were at least 25 homicides committed by monitored offenders in the U.S. while under supervision. Although such incidents are rare relative to the number of people under supervision, they are severe enough to unsettle officials and the public alike.

EM-based systems are also subject to run-of-the-mill technology problems; a glitch in BI’s system in October 2010 allowed 16,000 offenders in 49 states to go unmonitored for 12 hours.

Battery life poses a persistent challenge. Many devices require being plugged into a wall outlet for hours each day—a burden for individuals who must leave home to work or comply with other supervision-related mandates, attend mandatory appointments, or those who lack stable housing.

Tampering is another concern. We are not aware of any formal estimate of the scope of intentional tampering with EM devices, but one state official estimated that about 10 percent of his clients cut off the monitor or deliberately let the battery die. A Florida survey also found that 85 percent of monitored individuals stated that the device did not make them less likely to abscond, which at least suggests an openness to removing the monitoring device. (The risk of getting caught may be greater because the supervisor quickly becomes aware of the abscond event, but the incentive to abscond may also be greater because being on EM is more restrictive than being on routine community supervision.) Some basic GPS units can even be disabled with nothing more than a layer of aluminum foil. Notably, over the last couple of years, some states have responded to anecdotes of tampering by increasing penalties for tampering with an EM device.

Many clients report that ankle monitors are uncomfortable and burdensome, particularly as they try to attempt into mainstream society. Most can tolerate the discomfort, but some cases go beyond irritation. For example, some diabetics experience swollen ankles, and others develop skin reactions where the strap touches their skin.

The effects on employment prospects are unclear. In the Florida survey,22% of monitored offenders reported being fired from a job due to EM. Even though the devices are mostly disguisable under pants, they may beep, require charging at awkward times, or produce a noticeable bulge.

Finally, cost is another obstacle. At roughly $300 per month, monitoring is significantly less expensive than incarceration. However, prisoners don’t pay for their own incarceration the way people on EM do.

The opportunity to improve EM technologies and programs

Technological improvements to EM devices can be made by integrating innovations from other fields. For example, new communication technologies used by the “wearables” and “location-based services” industries can be implemented into EM devices. GPS is often unreliable, especially indoors, where people spend most of their time. Adding additional capabilities (Wi-Fi detection, Bluetooth detection, accelerometers, etc.) could largely eliminate the satellite-drift problem (70% of an iPhone’s location fixes are accomplished using Wi-Fi rather than GPS). Some new EM devices have these modern capabilities, but most don’t.

Some electronic marketing companies are replacing bulky ankle hardware with app-based systems that run on a client’s smartphone. Tapping the phone’s GPS and communications tools cuts costs, boosts reliability, and feels less punitive. Most setups pair the app with a lightweight wearable—such as a Fitbit or smartwatch—to confirm that the phone stays with its owner. Both start-ups and established companies are racing to deploy these smartphone-driven solutions.

Once EM supervision transitions to a digital app, agencies can incorporate a range of new and useful features. The app can handle two-way messaging, appointment reminders, and check-ins and also links clients to education, job placement, housing, and other re-entry services. With a small hardware add-on, the same phone can even perform alcohol and drug tests. One start-up, for instance, offers a Bluetooth breathalyzer: the client blows into a device while the phone’s camera verifies their identity with the results uploading instantly.

Because public-sector procurement moves more slowly than the pace of consumer choice, widespread adoption of these recent technological improvements in EM will take time. Federal resources and philanthropic funding could accelerate the transition. Meanwhile, agencies can still optimize the use of existing ankle-monitor systems and expand their application to a broader range of clients.

Well-trained staff can dramatically cut down the torrent of electronic-monitoring alerts simply by fine-tuning the software. Take inclusion zones—the virtual circles that define where a client is allowed to be. If a supervisor sets the radius at 50 feet, even minor GPS drift can trigger repeated false alarms. Expanding the radius to 100 feet slashes those spurious alerts. True, widening the zone raises the risk of missing a real violation, but most agencies could safely adopt larger zones and strike a better balance between false positives and genuine threats.

Better triaging is also necessary and can be outsourced at a reasonable cost, while materially reducing the burden on officers so devices are deployed effectively. As monitoring services scale and more triage is outsourced, costs should decrease and quality should improve, driven by lower data processing costs and increased competition. Smaller jurisdictions can tap these efficiencies by contracting out their electronic monitoring programs.

Technical snags are also becoming easier to fix. New removable battery collars, for instance, allow users to swap and charge batteries without removing the device. Even with today’s technology, agencies can reduce false positives by deploying EM in settings less prone to false positives (even at some increased risk of false negatives) and streamlining their alert-triage protocols.

Applications of electronic monitoring

Electronic Monitoring—whether using today’s hardware or next-generation upgrades—could be applied in a wide variety of circumstances. Some of them are discussed below; the list is not exhaustive. In each case, though, the path should be similar: flesh out the effort with operational detail, launch a small pilot to confirm feasibility and gather early performance signals, expand to a larger trial (preferably with random assignment) to measure outcomes rigorously, and, if the results hold, adapt and roll out the model in other jurisdictions with input from both officials and prospective participants.`

Curfew as part of a probation sentence

A curfew is sometimes added to probation as a sanction for lower-level offenses, and in those cases, it has several advantages. For people who offend frequently, being forced indoors during “crime-prime” hours (about 10 p.m. – 4 a.m.) is a strong deterrent and incapacitation tool, yet it costs little, spares limited jail beds, and avoids the harms of incarceration. Properly set, a curfew need not interfere with work, job hunting, or other pro-social activities.

If curfew were imposed as part of the initial conditions of probation, then loosening curfew conditions (in particular, later hours) and the eventual termination of curfew could be used to create swift, certain, and fair rewards for compliance and achievement.

Enforcing curfew through in-person home checks is expensive and, for most probation departments, impractical at scale. EM solves that problem: it slashes enforcement costs while making undetected curfew violations far less likely to occur.

As devices add remote alcohol and drug testing, agencies can pair round-the-clock location tracking with strict sobriety requirements. This blend of curfew, continuous monitoring, and substance-use checks could turn probation into a credible alternative to jail or prison for even moderately serious offenses. Over time, tightly supervised community release might become the norm, with incarceration reserved for cases that truly demand it.

Curfew as a stand-alone sanction

New York City still grapples with fare evasion in the form of turnstile-jumping to dodge the $2.90 subway fare. The practice costs the transit system millions and poses public safety risks: when police arrested fare evaders in the late 1970s, they recovered many illegal weapons and significantly reduced robberies and disorder in stations. Yet full custodial arrests proved too costly, so the city shifted to summonses; evasion soon climbed again, most tickets went unpaid, and the backlog of bench warrants ballooned. Fare-beating is now one of the most frequent violations among probationers, leaving the Probation Department with few good options. The issue echoes a broader set of minor public-order offenses—such as public intoxication, disorderly conduct, public urination, graffiti, and other vandalism—that dominate the day-to-day workload of urban police departments.

Proportionate penalties for these minor offenses are hard to design. Jail is plainly excessive. Fines can work for those with means, but for low-income offenders they only deepen poverty, accumulate unpaid debt, and carry harsh side effects such as license suspensions. Community service sounds appealing, yet it is costly and logistically complex. Simply ignoring the conduct, however, degrades quality of life, undermines respect for the law, and heightens fear of crime well beyond the actual incidence of serious offenses.

A low-impact alternative is a brief, electronically enforced curfew—say, requiring the person to remain home from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. the following weekend. Backed by EM instead of labor-intensive home visits, this sanction is sufficiently unpleasant to deter future violations while remaining inexpensive and minimally disruptive.

Curfew for violators of conditions of community corrections

Probation succeeds only when its rules can be enforced, and that hinges on credible sanctions. Penalties that cost the agency too much are used sparingly; penalties that are too harsh—such as reincarceration or hefty fines—often backfire. If the response is delayed by a lengthy hearing or by a sanction scheduled far in the future, it will be ineffective. Likewise, a prompt but toothless reaction (for instance, a mere verbal warning) does little to curb misconduct. Because every sanction consumes limited staff time and resources, high violation rates can trigger a vicious cycle: violations multiply, the odds of any one violation being punished plummet, and the low risk of consequence fuels still more non-compliance.

An ideal probation sanction should be swift, inexpensive for the agency, and unpleasant enough to deter violations without undermining a client’s chances of returning to a lawful life. A short curfew–even just one day–meets those requirements: it is highly aversive, requires no jail space, can start immediately, and can be scheduled so it does not disrupt employment or other prosocial obligations.

Curfew is not a universal solution, of course. Forcing a domestic abuser to stay home may punish the victim more than the offender, and people who are homeless or “couch-surfing” cannot be confined to a residence they lack. Still, a substantial share of probationers have stable housing and could benefit from this targeted, cost-effective sanction.

Electronic location tracking can slash the cost of enforcing curfew. But the curfew matters only if a violation reliably triggers a sanction. Early breaches may result in a tighter schedule, an extended curfew, or the loss of specific privileges. Persistent non-compliance should lead to brief stints of custody, imposed through a “swift, certain, and fair” formula rather than discretionary hearings. Evidence from such programs shows that when every violation meets a prompt response, violations quickly drop to manageable levels.

When the alternative is no punishment at all, curfew offers clear benefits: higher compliance, improved social functioning, and lower recidivism rates. At the other end of the spectrum, it can replace full revocation and reincarceration. The key research question, then, is how the deterrent and incapacitation power of an electronically monitored curfew stacks up against a jail cell—both for the individual and the system’s bottom line.

Position monitoring and pre-trial release

Roughly half a million people sit in local jails on any given day—about as many as the entire U.S. jail and prison population in 1980. Most are pre-trial detainees held either without bail because a judge deems them too risky or because they cannot afford bail or a bondsman’s fee. While some defendants are genuinely too dangerous to release, most are not. But judges often keep more people behind bars than necessary—not out of malice, but out of fear of releasing the “wrong one.” However, jails are costly to operate and can often undermine individuals’ stability. Time spent in jail, whether pre-trial or post-conviction, can damage defendants’ employment and family ties. Pre-trial detention, in particular, can pressure people into guilty pleas; it also could tilt judges toward harsher sentences. Given these harms—and their unequal impact by race and income—courts are increasingly skeptical of widespread “punishment before trial.”

Risk-assessment tools can estimate both a defendant’s chance of reoffending and the likely seriousness of any new crimes. Low-risk individuals can be released on their own recognizance, while truly high-risk defendants may still require pre-trial detention. That leaves a middle tier—people who are too risky for unsupervised release but not so dangerous that jail is justified—who could be managed with tighter supervision rather than simply releasing them on their own recognizance.

At one end of the spectrum, “tighter management” can mean full house arrest—a common alternative to pre-trial detention, though typically affordable only for well-off defendants who can cover the fees. More often, judges may conclude that a defendant can remain at liberty if the court can track their whereabouts in real time. Between these poles lies a middle group who could be released subject to both continuous location monitoring and a set curfew. Whatever form this supervision takes, absconding must carry swift, serious penalties, and the program’s success should be judged above all by how rarely defendants go missing.

Location tracking for incapacitation and deterrence

One aim of probation and parole is “specific deterrence”: keeping someone under close supervision should raise the odds of detection if they break the law again. Traditional supervision rarely meets that goal, but GPS tracking can. When a client’s real-time location is logged, investigators can cross-check those coordinates against the time and place of new crimes. A match is not enough on its own to file charges, yet it sharpens investigative focus, and the same data can clear an innocent person by providing an electronic alibi. For crew-based crimes, GPS offers another benefit: co-conspirators are less likely to include someone whose every movement is recorded.

Giving police a live feed of probationers’ or parolees’ movements invites profiling and harassment. A better approach is to let community-corrections officers match GPS logs against the time and place of newly reported crimes. Massachusetts has piloted this model, and although no formal evaluation has been published, early results appear promising.

Counseling should accompany the monitoring. Clients need to understand that their anklets can place them at—or clear them from—the scene of any fresh offense. At monthly check-ins, officers can review a client’s recent travel record to anchor the conversation in facts: a claim of diligent job-hunting, for instance, will be confirmed or contradicted by the data, just as lingering on the same corner where the client was once arrested for selling cocaine will quickly come to light.

This program is well suited to a low-cost randomized trial with three groups: (1) a control group that receives no intervention, (2) a group monitored with GPS tracking and crime-location matching, and (3) a group that receives the same tracking plus counseling.

Conclusion

Electronic position monitoring unlocks a suite of community-corrections strategies that can both cut incarceration and strengthen public safety. EM turns curfew into a versatile tool—usable as an immediate penalty for low-level offenses, a probation condition for more serious cases, or a quick response to rule violations that would otherwise land someone in jail. GPS tracking can also replace cash bail by allowing for the release of a large number of people on recognizance, and it is central to “graduated reintegration” models that move people out of prison earlier through phased supervision. In every scenario, matching a client’s movement history against the time and place of new crimes adds a powerful layer of deterrence.

Shifting from single-purpose GPS anklets to smartphone-based monitoring would lower costs, ease discomfort and stigma, and boost accuracy and reliability. A phone can handle video check-ins, text reminders, motivational messages, and even on-the-spot alcohol or drug tests, while still functioning as a regular phone, so the expense is not a dead loss for the client.

Unfortunately, today’s procurement rules and market structure move too slowly to keep pace with these advances. Federal agencies and philanthropies could accelerate innovation by creating stronger incentives, for example, underwriting a national database of supervision and monitoring data. Such a resource would support rigorous evaluations and reward vendors whose technology or service clearly outperforms the competition.

Unexpected results are inevitable; therefore, every new use of EM should begin with a pilot and, whenever possible, a randomized trial. A comprehensive, energetic program of such experiments would yield valuable lessons and potentially substantial payoffs.