This essay highlights ideas in the author’s upcoming book The Permanent Problem: The Uncertain Transition from Mass Plenty to Mass Flourishing, scheduled for release on January 5, 2026, by Oxford University Press.

The past year has shown that the concept of “abundance” has legs. A bestselling book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. An expanding shelf of other well-received volumes on similar themes. Policy organizations with abundance in their name. The simultaneous emergence of a more right-coded “progress” movement that identifies many of the same problems and offers similar solutions. An annual Abundance Conference, the most recent with 15 different organizations represented on its host committee. A new, bipartisan, abundance-themed congressional Build America Caucus. And a vociferous, sometimes hysterical opposition whose main impact is to Streisand-effect its target to even greater prominence.

OK, so abundance has legs — but what kind of creature are they attached to? And where are those legs capable of taking us? What are the appropriate contours of the concept — we want an abundance of what, exactly? And what’s the social vision behind this desire for more — we want abundance for what?

What fits inside the abundance frame?

An early challenge for the abundance movement is figuring out — and limiting — its scope. “I think we could all use a reminder that while ‘abundance’ has real value as a conceptual frame,” my Niskanen Center colleague Matthew Yglesias wrote recently, “there are limits to what we can address through lumping.” He elaborated here:

What matters is whether the ideas are good. It would be easy to think up policies to make alcohol more abundant, but that would be bad — alcohol fuels crime and traffic accidents and is unhealthy. America’s recent experiment with an abundance agenda for sports gambling seems to have been harmful. More broadly, though I have already disavowed the “smartphone theory of everything,” it absolutely seems to me that the superabundance of streaming video that we now enjoy is creating a lot of problems for society.

My old friend Adrian Wooldridge has made the case for an “anti-abundance agenda” to address the addictive junk that we can’t stop stuffing into our mouths and minds:

The abundance agenda needs to be balanced by an anti-abundance agenda. For in many significant areas of life, we suffer from a crisis of overproduction rather than underproduction — too much stuff (or stimulation) rather than too little. This overproduction is bad for our physical and mental health. And the bizarre combination of too much bad abundance and too little good abundance (like too much bad cholesterol and too little good cholesterol) is at the root of our civilizational malaise.

The birth of abundance: A sense of brokenness

The idea of an “abundance agenda” made its first appearance in a Derek Thompson piece for The Atlantic in January 2022, and a growing group of wonks and scribblers has been running with it ever since. The unifying theme of this developing agenda has been combating dysfunctional government policies and institutional structures that restrict the supply of key goods and services. Either the government is actively blocking private actors from meeting market demand, or it’s unable to get out of its own way in providing public services.

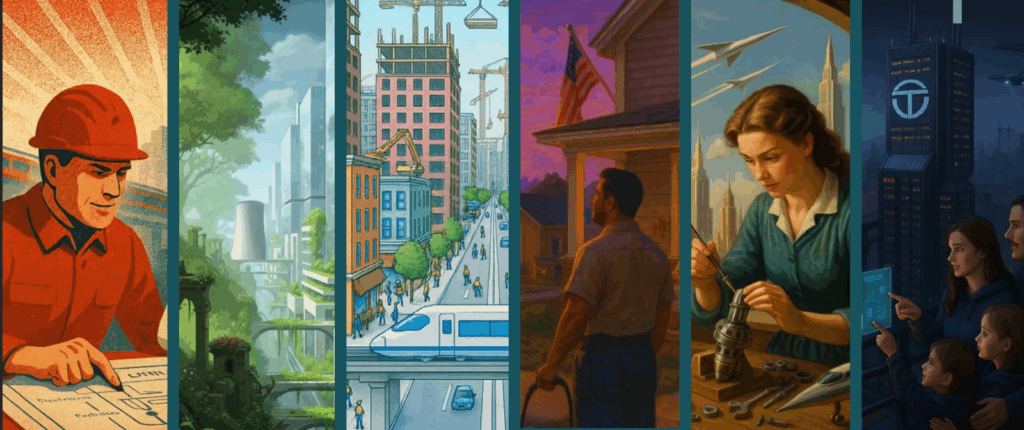

The “Big Three” core concerns that have emerged thus far are housing, energy, and transportation:

- In housing, zoning and other land-use regulations have resulted in a rolling affordability crisis for would-be homebuyers in metro areas across the nation.

- In energy, over-the-top permitting restrictions are slowing the transition to clean energy.

- In transportation, a tangled mess of “state capacity” deficits has sent costs per road- and track-mile in the U.S. soaring to multiples of those in other advanced countries.

Meanwhile, efforts to broaden the abundance agenda have focused on problems as varied as the bureaucratization of scientific research, which gets its own chapter in Klein and Thompson’s Abundance, and the host of supply constraints that drive up healthcare costs.

From the dots connected thus far, we get a pretty clear picture of the kinds of policy issues that fit comfortably within the abundance frame. The point isn’t to boost the supply of every bit of frippery that 21st century affluence can support a market for. The abundance idea has taken off because of its focus on core inputs to a high-functioning economy and core elements of a typical family’s budget. When you can’t afford a decent home anywhere near where you work, the economy feels broken no matter what the topline stats may say. When a big public construction project can’t get completed without huge delays and cost overruns — or maybe can’t get completed, period — government feels broken.

The abundance movement has arisen in response to this sense of brokenness.

Furthermore, there needs to be some identifiable bottleneck that is holding back supply and driving up prices: A reform agenda needs something dysfunctional to reform. When you examine the targets for reform that the abundance movement has identified and look for the underlying causes of dysfunction, you generally find some combination of regulatory capture, in which powerful insiders dominate the policymaking process and twist the rules to feather their nests by restricting competition — and thereby limiting supply — and a lack of state capacity typically brought about by the buildup of “red tape,” the old-fashioned name for what we’re now beginning to refer to as the “procedure fetish.”

Abundance and the atoms/bits divide

Though the ideas behind the abundance movement originated in technocratic policy wonkery, they resonate at much deeper levels. That’s because when you look at where abundance is most conspicuously lacking — namely, the movement’s central targets of housing, energy, and transportation — you see that that the common denominator is blocked action in the physical world — the world of atoms as opposed to the world of bits.1

The idea of lost abundance thus ties into the disillusionment with the digital revolution — and, with it, the growing recognition of the need to reprioritize and reengage with the physical world — that has been steadily building cultural momentum over the past decade or so.

This cultural turn started with the same kind of narrow, technocratic focus that has animated the abundance movement to date — namely, disappointment in the wake of the Great Recession with the slow pace of productivity growth and underlying technological progress. Out of these discontents has emerged the fledgling “progress” movement, which overlaps substantially with abundance in its analysis and goals while expressing them in more right-coded terminology. We can trace the origins of this movement to Peter Thiel’s memorable lament from 2011: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”2

Previously, in the decades since Ronald Reagan first won the presidency, boosters of free markets and low taxation (i.e., people like Thiel) had been almost uniformly bullish on U.S. economic performance and ongoing technological prowess, dismissing concerns about “deindustrialization” voiced by generally left-leaning advocates of “industrial policy” during the during the 1980s and early ’90s. “Computer chips, potato chips — what’s the difference?” a quote attributed to Michael Boskin, George H. W. Bush’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, summarized their viewpoint. What mattered was the overall level of GDP, not its components.

The internet boom that began shortly thereafter — and with it the resumption of robust productivity growth after a prolonged slump during the 1970s and ’80s — only strengthened the belief on the free-market side that the “dematerialization” of economic life was the path of progress. (The roaring stock market of the ’80s and ’90s didn’t hurt, either.) If anybody ever looked backed at the old midcentury dreams of continued progress in the physical world — moon bases and underwater cities, nuclear fusion, supersonic air travel, and, yes, flying cars — it was only in rueful acknowledgment of the impossibility of predicting the course of technological advance. When I read Robert Heinlein’s great juvenile sci-fi novels aloud to my boys back in the ’90s and early ’00s, we all laughed when they used slide rules to calculate the jump to light speed.

Then came the Great Recession and the subsequent collapse of productivity growth, which triggered a rapid shift in perspective. No longer did the ’90s boom look like a resumption of normal vitality after the temporary slump of the ’70s and ’80s; now the ’90s looked like an exception to the new normal of low growth. In 2011, the same year that Thiel’s oft-repeated crack about flying cars first appeared, Tyler Cowen came out with The Great Stagnation, which includes Thiel in its dedication. J. Storrs Hall followed up in 2018 with his Thiel-inspired Where Is My Flying Car?, a quirky, brilliant book that derided the cultural turn of the 1970s that knocked us off the path of progress in the physical world and which I’ve termed the anti-Promethean backlash. The following year, Cowen teamed up with Stripe cofounder Patrick Collison to write “We Need a New Science of Progress” for The Atlantic — and the new progress movement was off the ground.

This turn in ideas was occurring just as changing circumstances provided both a push and a pull in the direction of renewed interest in “hard tech” — i.e., innovation in the world of atoms. The looming threat of climate change, combined with the emergence of China as a technologically formidable adversary, posed serious and difficult challenges that could not be met with a new phone app.

Meanwhile, a couple of unexpected spurts of technological progress — rapidly declining production costs for solar and wind power, and SpaceX’s similarly spectacular reductions in launch costs — reawakened entrepreneurial optimism and ambition in the hard-tech sector. Now we’re seeing promising developments and increasing investment in nuclear energy, including nuclear fusion, and in advanced geothermal power and supersonic flight.

Can the abundance movement scale?

The combination of the progress movement and the hard-tech mini-boom is helping to reorient policymaking elites toward reengagement with the physical world, an unabashedly good thing. However, worries about the long-term rate of growth and the organization of scientific research are far too abstract and recondite to stir the wider public and provoke changes in mass culture. The problems of affordability that the abundance agenda targets are much more salient to the everyday concerns of ordinary people but on their own aren’t enough to awaken the passions out of which broad-based social movements arise.

What is packing an emotional wallop is our growing disenchantment with the other side of the atoms/bits divide. Here, Thiel really was ahead of the curve with his “flying cars” line: He was throwing shade at social media just as the hit movie The Social Network was inspiring a new generation of tech founders, and as the early hopes of the “Arab Spring” seemed to demonstrate social media’s power to promote positive change through “people power.”

Trump’s surprising 2016 win, and the surrounding controversy over Russian and other online “misinformation” during the campaign, marked the turning point. While fears of the purposeful manipulation of public opinion have proved overblown, we have met the enemy online, and it is us: The broader perception that social media elevated extremists and degraded discourse overall was spot on. Is it even possible to imagine Trump’s rise in a pre-Twitter world?

From there, the bottom dropped out of the dream that the internet would “connect the world” and bring us all together. On the contrary, it became increasingly clear that our smartphones were weapons of mass distraction that we were training compulsively on ourselves. Teenage driving, after-school employment, and just hanging out with friends all declined as kids withdrew into the virtual simulacrum. Not coincidentally, mental and emotional problems among the young began skyrocketing. People even started walking blindly into traffic while staring at their phones, or falling off cliffs while posing for selfies — these were outliers, but most of us have sat at a dinner table in stony silence with everyone lost in their own social media feeds. Virtually all of us have felt our attention spans slipping. A century of “Flynn effect” increases in raw IQ scores has begun to reverse itself. Personality tests reveal precisely the trends you might expect: rising neuroticism, falling extraversion and agreeableness, and a collapse in conscientiousness.

‘Mass brain rot’

The latest twist has come with the astonishing breakthroughs achieved by ChatGPT and other large language models. Once again, we are confronted with a miraculous technology that can amplify our brainpower in potentially transformative ways. And once again, we are watching it steadily evolve, under the selection pressures of ferocious commercial competition to monopolize and monetize our attention, into yet another source of mass brain rot. Students are using it en masse to cheat themselves out of the hassle of learning anything in school. It’s a problem that started well before ChatGPT showed up and now reveals itself, even in the most elite institutions, in the widespread inability to work through and comprehend college-level reading material.

Moving from the pathetic to the outright creepy, we’re seeing increasing reports of desperately lonely people getting hooked on “relationships” with chatbots, as a result of which “AI-induced psychosis” has now entered our vocabulary. And employing the utter shamelessness that has emerged as the characteristic vice of the 21st century, Elon Musk’s xAI has already come out with pornographic “waifu” AI companions, and now OpenAI plans to follow suit in December.

Just as the post-2009 slump prompted a reconsideration of the past half-century of U.S. economic performance, so has the one-two punch of social media- and AI-related dysfunction triggered what looks like the beginnings of a wholesale reappraisal of the mass media era. The “What, me worry?” side of the debate points out correctly that dire warnings about media consumption are nothing new; in centuries past, people got the vapors over the deleterious effects of novel reading. This kind of response used to carry the day, but increasingly people are coming around to the idea that, at least since the advent of TV, the Chicken Littles have had a point. Here’s Matt Yglesias, for example: “The multi-generation moral panic about improved video entertainment driving social isolation is largely correct. The technology keeps improving, but it’s not making our lives better.”

I’m certainly an example of this: I had no use for Neil Postman’s diatribe against TV when it came out in the 1980s, and now I can’t stop quoting the man. And I’m not alone: Postman is cropping up all over the place these days. Derek Thompson dropped this amusing footnote after citing him recently:

Believe me, I tried to keep old Postman out of this — he’s over-exposed enough these days — but as I wrote, I could hear the ghostly thump-thump-thump of his posthumous fists knocking on the door of this essay, and I had to let him in.

Worries about “post-literacy” are now going viral.

And this shift in opinion isn’t confined to scribblers. The movement to ban phones in schools is gaining traction and registering wins all over the world. A recent survey found that 68 percent of Gen Z adults feel nostalgia for times before they were born — i.e, before the digital tsunami swallowed everything. Jake Auchincloss, a Democratic member of Congress from Massachusetts, refers to social media, online pornography, and online sports gambling as “digital dopamine” and proposes that we treat them like we treat alcohol or tobacco: restrict use by children and subject online providers to special sin taxes — for example, on advertising revenue.

Thompson, who interviewed Auchincloss for his podcast, sees him and Republican Utah Governor Spencer Cox, who castigated social media as a “cancer on our society” in the aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, as representing a new “touch grass populism.” “Rather than identify the enemy of America as specifically left, or right, or corporate, or foreign,” Thompson wrote on X recently, “the enemy they name is the digital hellscapes that summon the worst demons of our nature. They call us to re-invest our attention and our resources in the world of people and atoms.”

Raising the abundance movement’s ambitions

This wider cultural turn against the sordid excesses of online life could be the wave that carries that abundance idea from its current niche status — the preoccupation of technocratic elites — and transforms it into a genuinely popular social movement. The negative motivations are already in place. Fears of genuinely dystopian dangers have been awakened — and what’s more, the people most exposed to those dangers are our children, rousing our passions all the more.

What is needed now is something clear and compelling to fight for. Abundance proponents must raise their ambitions and offer a bold, long-term vision for social change — one capable of inspiring hope and excitement, one that can unite people across current divisions and galvanize them into action.

The idea here is to appeal to ordinary people — not technology enthusiasts who thrill to the ingenuity and brilliance of the new and pathbreaking, but regular, risk-averse folks who tend to be suspicious of change because of their natural focus on holding onto what they’ve already got. To generate mass support for a resumption of large-scale progress in the physical world, you’ve got to hold out the prospect of big, tangible gains in ordinary people’s lives.

Jerusalem Demsas did an excellent job of making this point in a recent essay in her new publication The Argument, so let me quote her at some length:

Technologists and techno-optimists need to realize that the way we talk about innovation in articles, in ads, and in manifestos is often suboptimal for the goal of trying to convince skeptics of the value of progress. Take this 2023 “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” from Marc Andreessen that speaks in grandiose terms about the value of technology. I agree with much of what he writes, but it reflects an orientation toward scientific achievement that is more focused on the adventure of invention than it is the point of all that progress….

The broader problem for technologists is the widespread impression that their “progress” is merely about accomplishing something technically impressive even if that breakthrough has limited or destructive impacts on humanity. I don’t care that it’s incredibly difficult and impressive to create addictive short-form video platforms. I care that it’s wasting our time. I don’t really care if Mark Zuckerberg is a genius if the impact of his brilliance has been to create platforms that degrade social trust.

I want a techno-optimism that is focused on human progress. I want vaccines and geothermal energy and supersonic flight and high-speed trains. I want to venerate the boring technological achievements like the doctor who halved the C-section rate at his hospital and lowered the maternal mortality rate in California by recommending a “hemorrhage cart” that prevented new mothers from bleeding to death. Technology isn’t just about pushing the frontier. It’s about making people’s lives better.

So how can physical abundance transform lives for the better? We’re not talking about just piling up more random stuff; the offsite storage industry exists because we already have more stuff than we know what to do with. And we’re not talking about more trivial, enervating comforts and conveniences — not another “Uber for X,” not “smart” refrigerators and toasters with endless features that normal consumers can’t be bothered to learn and use.

What we want is a vision of the future in which physical abundance acts as a genuinely liberating force. But what is it that most ordinary people still yearn to be liberated from? Well, for one thing, people are increasingly feeling trapped in the endless digital maze and yearning for reconnection to the IRL physical and personal. A world in which the built macro environment is once again, after decades of stagnation, visibly changing and improving could go some ways toward restoring our collective sense of groundedness and real-world efficacy.

What I’m looking for, though, is some important deficiency in life offline that abundance can remedy. We are already so rich that economic growth and technological progress have substantially erased — to the extent they are capable of doing so, at any rate — various great deficits that traditionally menaced and degraded human existence: hunger, physical drudgery and suffering, ignorance, and premature death. Our main problem with food these days is too much of it. Our lives are now so sedentary that we pay money to go to gyms to get the physical exercise our bodies need. We have all the world’s knowledge available at our fingertips, just a click away on our phones — if we can be bothered to choose learning something new over the umpteenth TikTok video of the day. Funerals for children are now as rare as they are soul-wrecking; they were just as soul-wrecking before, but dreadfully commonplace.

The promise of abundance is that it can take us to the next level of rich, one in which another pervasive deficit that shadows our lives is progressively whittled away. It’s the deficit of freedom that comes from dependence on a lifetime of paid employment and that gives so many of our lives such ceaseless precarity.

The premise of my upcoming book is that the “economic problem” as John Maynard Keynes defined it has been solved. The threat of serious material deprivation has been pushed to the margins of life; as a result, the “permanent problem” of humanity — how to “live wisely and agreeably and well” with all our blessings — has now come into view.

But while it’s true that the vast majority of us in rich countries can now expect our basic material needs to be satisfied — and a whole bunch of less urgent needs and wants as well — it’s true subject to an important qualification: We can expect to satisfy our basic needs and many more besides provided we spend a big chunk of our waking hours throughout our decades of adulthood working at some job to earn the money to pay for it all. And for most of us, that job requires us to do work that we would never choose to do for its own sake. A lucky minority is employed in work that, even if we might not keep doing it if we won the lottery, is sufficiently challenging and absorbing that we derive many intrinsic rewards from it as well as the extrinsic reward of the paycheck. But for all too many of us, those intrinsic rewards are few and fleeting, outweighed considerably by spiritually emptying tedium and stress. And even if we hate our jobs, we usually hate the idea of losing them even more. Yet this happens regularly, often for reasons completely outside our control.

The implicit vision of progress that underlies our current economic order — and it’s rarely stated explicitly, maybe because too many people would immediately see through it — assumes that mass adult employment, with employment-to-population ratios comfortably above 50 percent, is a necessary and enduring feature of modern economic life. Progress, then, takes the form of better (i.e., more intrinsically rewarding) jobs at higher pay with a steady rollout of new and improved gizmos and doodads to buy.

No wonder people are pessimistic about the future. I’ve come to the conclusion that the overall quality of paid employment opportunities is unlikely to keep improving. And we know that many of the new and improved gizmos and doodads we’ve been buying are actually making our lives worse; there’s certainly no reason to expect that we’re going to get to living “wisely and agreeably and well” through a wider array of possible consumer purchases.

But there’s another possible future, and the idea of physical abundance points the way. Imagine a future in which core elements of a household budget — housing, transportation, energy, healthcare — are now so cheap that it’s possible to fund a comfortable retirement with a fraction of the lifetime working hours needed today. Imagine a social movement — or perhaps a competing variety of social movements — that seizes upon this possibility and encourages lifestyles designed to minimize dependence on paid employment. You’d see lots of people retiring in their 30s and 40s, a higher share of part-time workers among those who do work, and more people entering and exiting the labor force episodically as life circumstances change. And you’d see a lot more small businesses, online or in the home.

This is the next level of rich that abundance-based policies can get us to: societies in which mass full-time employment is no longer the norm — not because people are dropping out of the workforce under competitive pressure from machines, but because people are “graduating” from work for pay because they now have better ways to spend their time. The prize that abundance offers us, then, is a big and ongoing increase in the ranks of the independently wealthy.

Footnotes:

- Abundance-related ideas are also resonating at the level of partisan politics. In their book, Klein and Thompson pitch abundance as a new organizing principle for the center-left, and this possibility has figured prominently in Democrats’ soul-searching after their disastrous 2024 election losses. I won’t address this political dimension in the present essay as I’ve already discussed it here, here, and here. ↩︎

- The line first appeared in a manifesto published in 2011 by the Founders Fund, a venture capital firm cofounded by Thiel. Thiel has used the line regularly since. ↩︎