The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) marks an important turning point in the history of the Child Tax Credit (CTC), with the inclusion of permanent indexation provisions for the first time since the credit’s introduction. Indexation, which protects families from inflation by automatically adjusting the value of tax benefits to keep pace with increases in the cost- of-living, has been a standard part of healthy tax codes for over half a century–yet until now, the CTC has been a notable exception.

Before the 1970s, most countries set their tax provisions in nominal terms so they were not automatically adjusted for inflation. In the U.S., Congress would set the value of personal exemptions in nominal dollars. In periods of low inflation, the real value of these provisions declined only slightly each year. From time to time, Congress may legislate increases to compensate for this decline. For many policymakers, the onset of stagflation in the early 1970s–when annual inflation rates sometimes reached 10%– suddenly made indexation a more attractive option.

Many members of Congress–especially in the House–initially balked at the idea of relinquishing discretionary control over tax policy. But Senate Republicans made indexing a priority, and the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 included provisions to adjust the standard deduction, personal exemptions, and tax brackets for inflation starting in 1985. Congress expanded this approach in the 1986 tax reforms by also indexing the Earned Income Tax Credit’s maximum benefit and income thresholds.

By the time Congress introduced the Child Tax Credit as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, inflation had returned to normal levels and deficit reduction was now a major priority. As a result, Congress did not index the new credit as it had done for almost all of the rest of the federal tax code. This began a 20-year period of steady erosion of the CTC’s inflation-adjusted value, interrupted by the occasional legislative expansion.

The child tax credit and inflation since 2017

Congress made several significant changes–some temporary and some permanent–related to indexation and the Child Tax Credit as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. First, it updated the way we index the tax code, shifting from the use of the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to the Chained Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U). Proponents maintain that this new index better reflects changes in the cost of living for families over time by accounting for their ability to shift their consumption patterns in response to relative price changes. These changes were made permanent as part of the original bill.

The TCJA also eliminated personal exemptions and allocated the savings to a larger standard deduction and a higher child tax credit. These reforms significantly shaped how inflation affects families. The expanded standard deduction, like the personal exemptions it replaced, was already indexed to inflation. In contrast, the changes to the CTC were temporary and less consistent.

Working-class families traded in an indexed dependent exemption for a partially indexed refundable portion of the CTC. The TCJA reduced the phase-in threshold for the refundable portion of the CTC from $3,000 to $2,500 while leaving it non-indexed and raised the maximum credit from $1,000 to $1,400 and indexed it for the first time ever. Unlike other provisions, the formula stipulated that the credit will only be adjusted in increments of $100. These provisions had two subtle impacts for many working-class families.

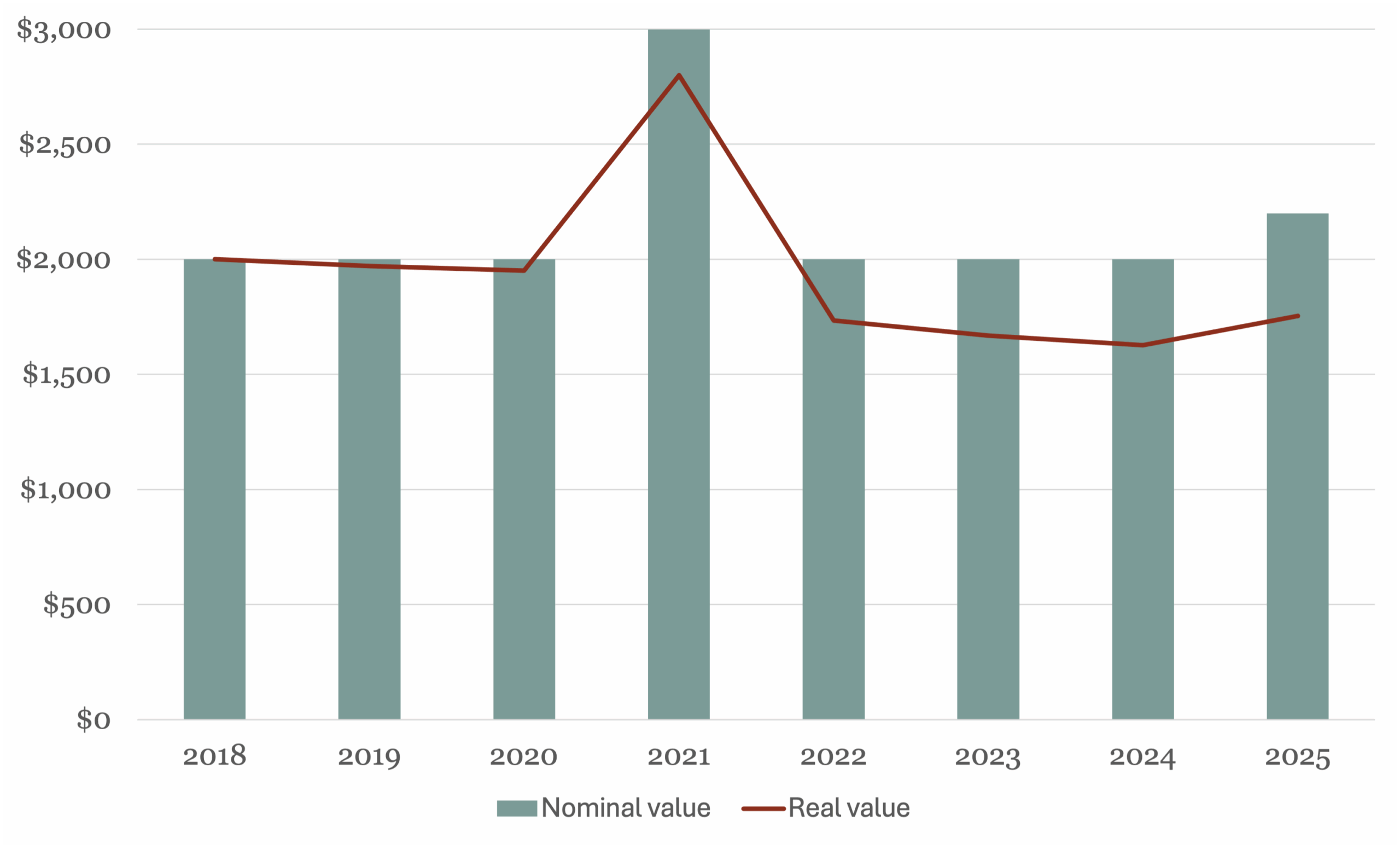

First, indexing the refundable portion of the credit ended the practice where Congress would increase the value in nominal terms only to watch it be eroded over time in real terms. As Figure 1 shows, the nominal growth in the value of the refundable portion of the credit–from $1,400 in 2018 to $1,700 in 2025–has kept its inflation-adjusted value relatively stable over time. This change finally brought the refundable portion in line with the spirit of the changes made to the rest of the tax code in 1986.

Figure 1: Maximum credit (refundable portion) in real and nominal dollars

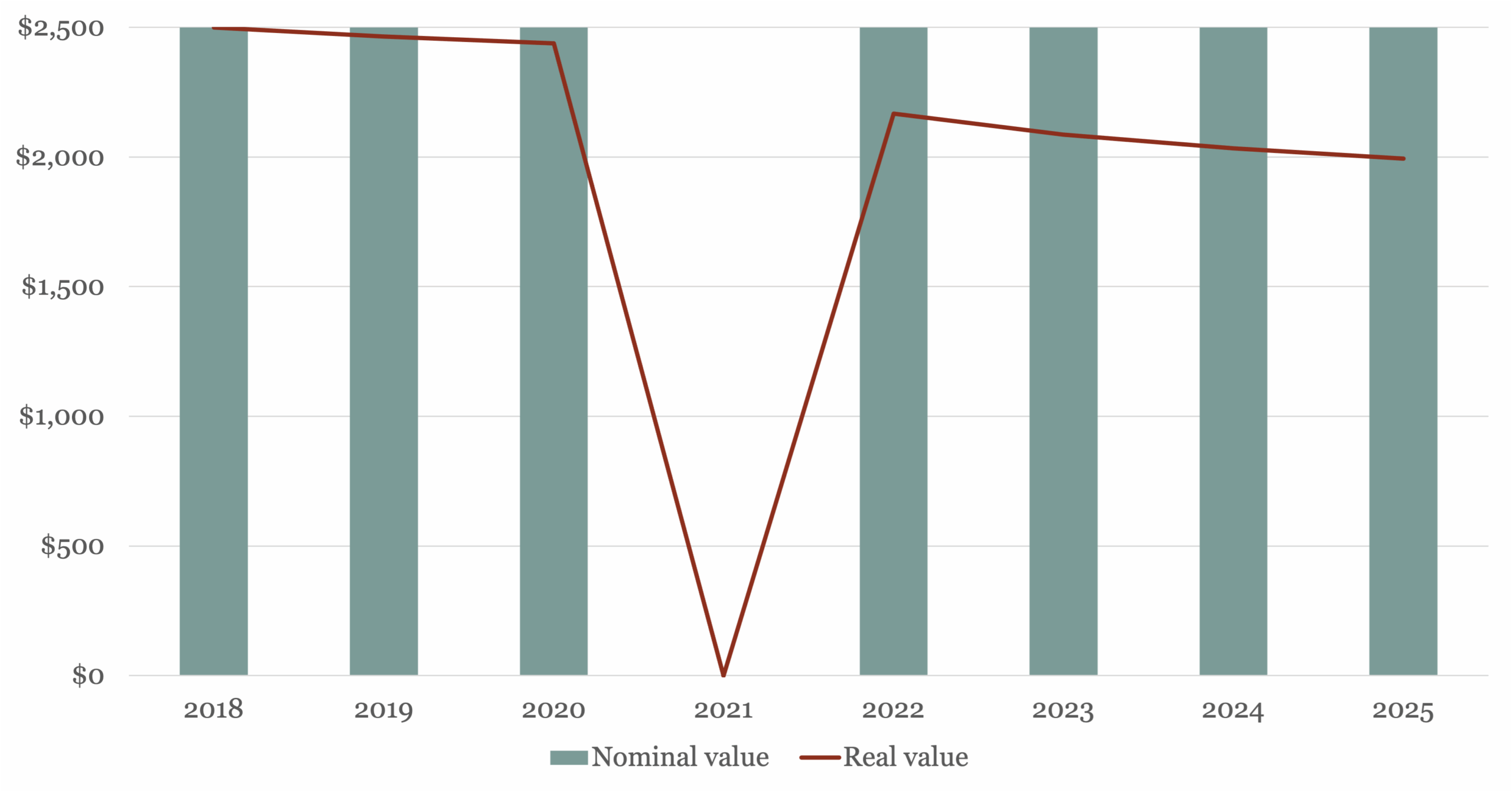

Second, the continued non-indexation of the earnings threshold at a lower base amount has slightly expanded access to the refundable portion of the credit. While the nominal value of the earnings threshold has remained $2,500 since 2018, Figure 2 shows that the real value has fallen over time as a result of non-indexation. It has become and will continue to become a bit easier for families to reach that threshold–and by extension, the threshold for the full refundable portion of the credit–over time.

Figure 2: Earnings threshold for phase-in (refundable portion) in real and nominal dollars

The picture is different for many middle and upper-class families who traded in an indexed dependent exemption for a non-indexed nonrefundable portion of the CTC. As others have shown, this led to shrinking benefits for an increasing number of these families over time.

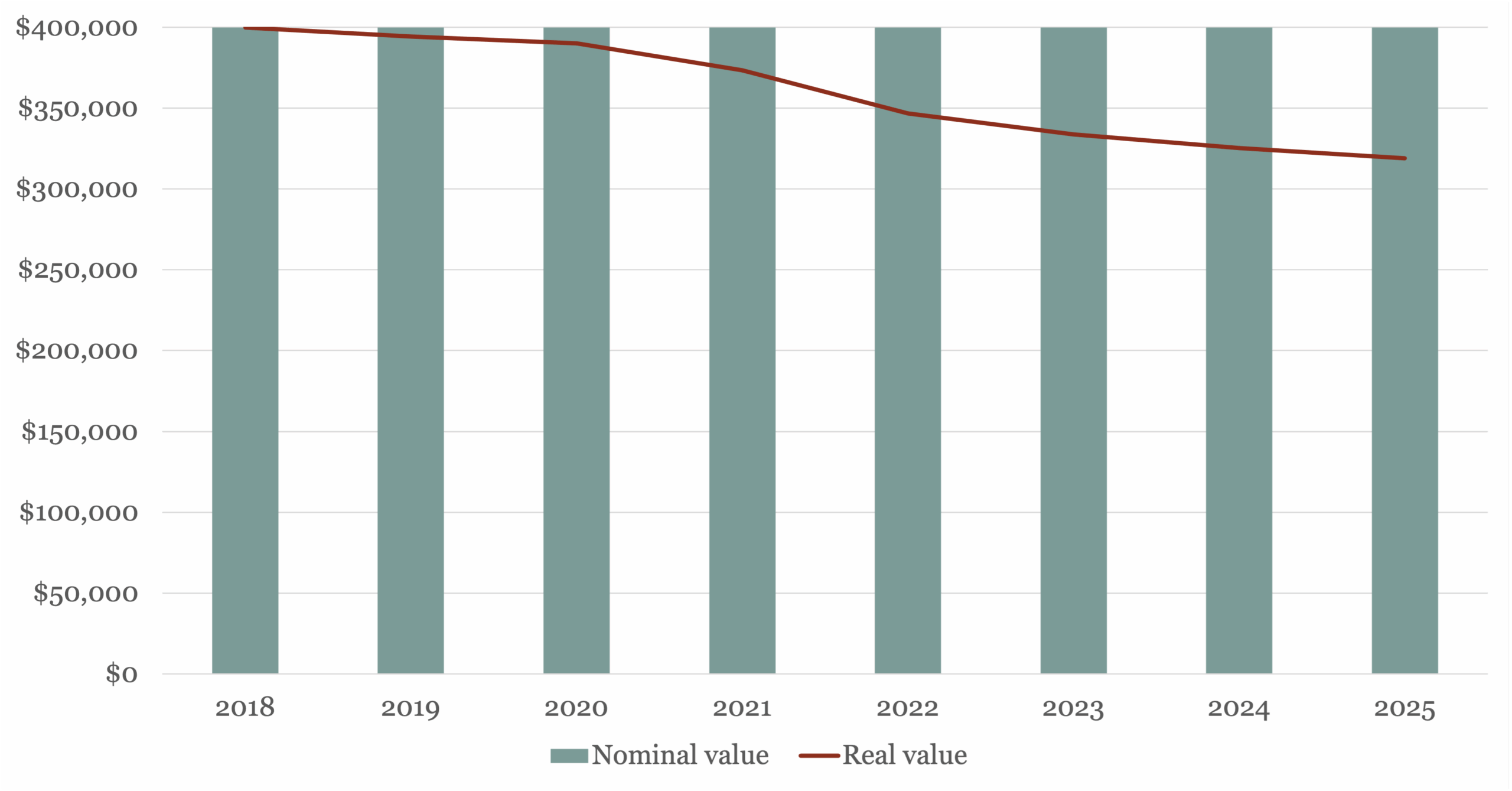

As part of TCJA, Congress increased the phase-out threshold for the CTC from $75,000 to $200,000 for heads of household and from $110,000 to $400,000 for married filers. Congress continued not to index these thresholds though. While the nominal value of the earnings threshold has remained at $200,000/$400,000 since 2018, Figure 3 illustrates that the real value has fallen over time as a result of non-indexation. TCJA initially provided a substantial boost for upper-income families which has steadily declined over time as more of those families move into the partial or no credit zone.

Figure 3: Earnings threshold for phase out (married filers) in real and nominal dollars

The TCJA made the three changes temporary, set to expire at the end of 2025. While OBBB did not make any additional changes to the refundable portion of the credit or to the earnings threshold, it did make all these provisions permanent. Beyond permanency, the most significant changes in OBBB were related to the nonrefundable portion of the CTC.

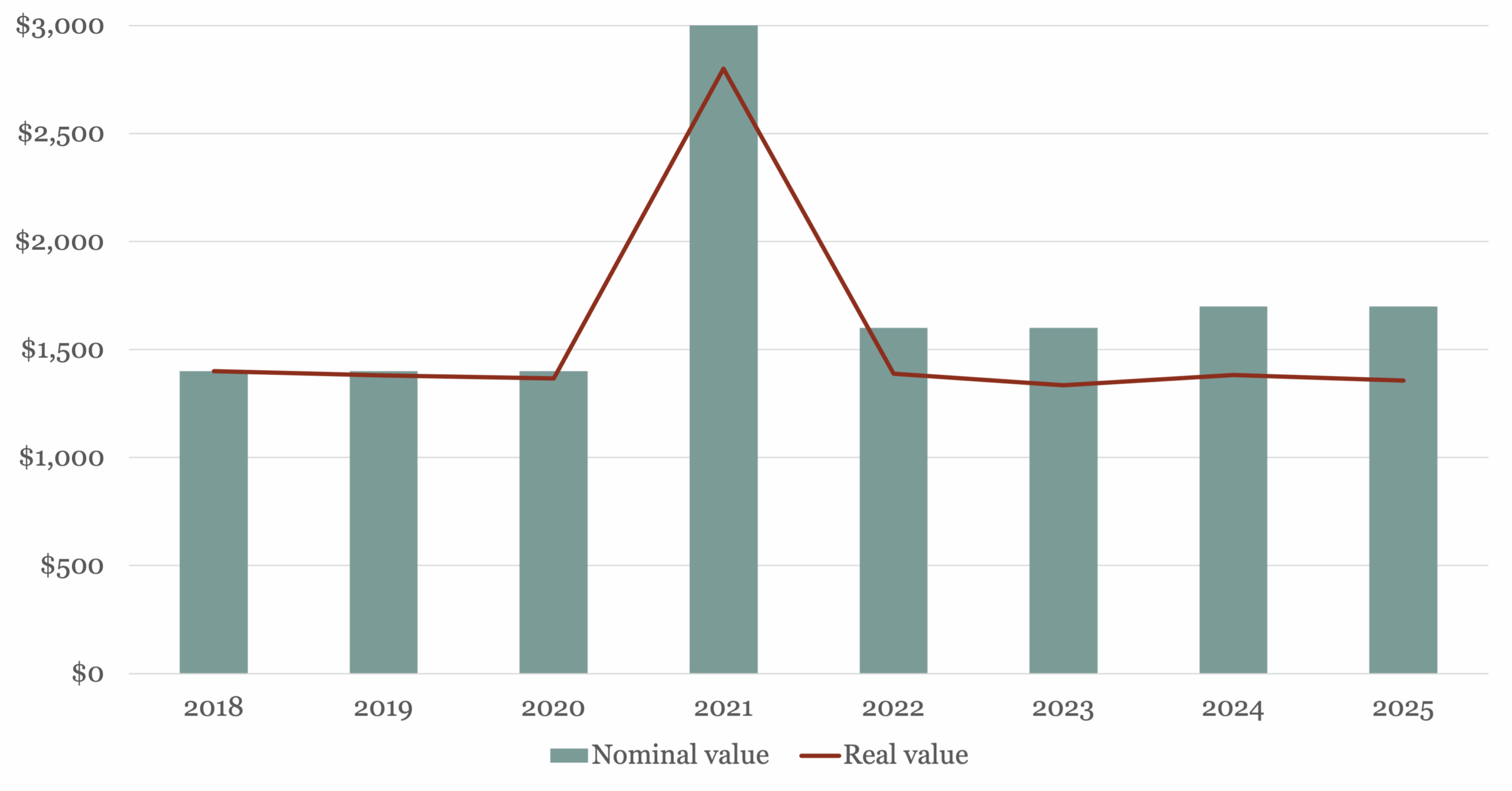

First, Congress increased the nonrefundable portion of the credit from $2,000 to $2,200. Second, it finally indexed the credit starting in 2025. Unlike the refundable portion–which has been indexed since 2017–the nonrefundable portion had remained non-indexed until the passage of OBBB last month. As Figure 3 illustrates, the real value of the credit eroded so extensively over time, and the $200 increase in OBBB was insufficient to reverse that decline. To fully restore the credit’s value for most middle-class families, Congress would have needed to raise it to at least $2,500.

Figure 4: Maximum credit (nonrefundable portion) in real and nominal dollars

Two steps forward, one step back

Using the TCJA’s temporary changes made to the CTC as a baseline for comparison, OBBB’s changes can be best characterized as two steps forward, one step back. OBBB made crucial improvements by making the 2017 changes permanent and indexing the nonrefundable portion of the credit in line with the standard deduction, EITC, and refundable portion of the CTC. These are welcome reforms that previous Congresses overlooked for decades. However, we should also acknowledge that this indexation occurred after several years of high inflation, and the $200 boost included in OBBB does not fully compensate for the credit’s erosion over time.

Looking ahead, permanent indexation means Congress can focus on more comprehensive reforms that further simplify and extend the child tax credit, supporting more families with the cost of raising children.