State unemployment agencies face a persistent processing problem: they struggle to deliver benefits both accurately and on time. Last year, about 16 percent of payments were classified as improper–either overpayments or underpayments– and since the COVID-19 pandemic, the average state UI program has met federal timeliness standards in only two months. A major driver of these shortcomings is when agencies request and receive information on the reason for job separation, a critical step that too often delays or distorts benefit processing.

State UI agencies have limited claimant data at their disposal when workers submit UI claims. Quarterly wage data is regularly collected, helping determine if a claimant meets the earnings requirements. However, additional information is generally required from the former employer. Wage records from the most recent months may be requested. UI agencies must also confirm with former employers whether a job separation qualifies for benefits—for example, if an employee was laid off due to a lack of available work.

Depending on the state, employers have anywhere from four to fifteen days to respond to agency requests, but many fail to provide the required information. About 20 percent of improper payments result from slow or incomplete employer responses. Oftentimes, though, the problem lies not with employers but with the evaluation process itself. The U.S. Department of Labor determined that roughly three-quarters of overpayments are undetectable through standard agency procedures, and that “additional steps to secure employer information” could reduce such errors (Note: The DOL can assign responsibility for an error to multiple sources and stakeholders).

In a new report co-authored by Joshua McCabe, we argue that the United States can learn from Canada’s Employment Insurance program. Rather than waiting until workers submit benefit claims to ask employers for the reason for separation, the Canadian government collects this information once job separations occur. This proactivity helps Canada maintain an improper payment rate that is ten percentage points lower than the average U.S. state (Around five percent compared to 16 percent).

While UI agencies would need to adopt new procedures to collect separation reasons before claims are filed, some states already require employers to provide job-specific notices—either directly to the agency or to former employees—at the time of separation. These states could adapt their existing practices by ensuring that the notices are consistently sent to the UI agency, with the necessary separation information included.

What the U.S. can learn from Canada

Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) program covers a range of employee benefits, including unemployment, parental, maternity, sickness, and caregiving leave–all managed by Service Canada. At the heart of benefit processing is the Record of Employment (ROE), which employers are required to file whenever a worker experiences a seven-day interruption of earnings. The deadline to submit the ROE is generally five days after the end of a pay period, but can be fifteen days after the separation itself for employers with monthly pay periods.

For example, if a worker is laid off on April 1, the employer must submit a Record of Employment on:

- April 20th if the worker is paid on a biweekly basis (5 days after the end of the pay period); and

- April 16th if the worker is paid on a monthly basis (15 days after the separation date itself).

The ROE captures key information about both the employer and employee, including final work dates, total insurable hours and earnings. Crucially, it also records the reason for separation, a detail that determines whether a worker is eligible for benefits and, if so, which type. In total, employers must complete 22 categories of information.

U.S. states wouldn’t need to adopt every element of Canada’s ROE system—only the separation-related details necessary to strengthen program integrity and efficiency. While there is value in collecting the most up-to-date information about wages and hours worked at the time of separation, only 6% of UI improper payments in the United States relate to base period wages (the earnings considered for benefit eligibility). Separation issues are a much bigger source of error: one-fifth of improper payments stem from inadequate and/or untimely information about the reason for separation.

Which U.S. states are making progress

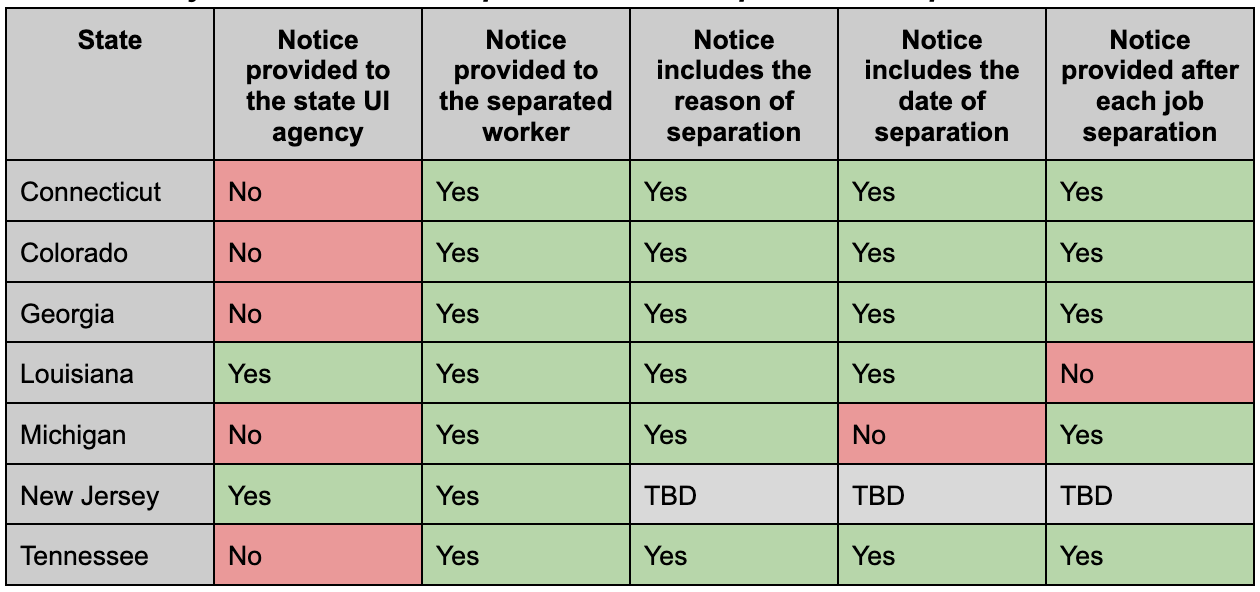

Seven U.S. states are in particularly optimal positions to adopt a Canadian-style separation certificate: Connecticut, Colorado, Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, and Tennessee. These states already require employers to provide a notice at the time of separation with job specific details (presented in the table below). Still, additional steps are necessary to completely eliminate the need to ask employers for separation information after UI claims are submitted.

In these states, separation notices are not always sent to the UI agency after each job separation–and the details provided on why and when the worker left may be insufficient.

States already with substantive separation notice requirements in place

Louisiana and New Jersey both have laws requiring employers to submit separation notices to their state UI agency. Yet, these states may not get the most out of these mandatory notices. In Louisiana, employers are only required to proactively report to the agency when disqualifying separations occur. The UI agency may still need to follow up with employers about separation information after claims are submitted. New Jersey is in the process of rolling out its own separation notice, but may address similar gaps before finalizing its forms. To maximize effectiveness, separation notices must be submitted after every job separation, ensuring agencies have the information they need upfront and eliminating the need for post-claim follow-ups.

Meanwhile, Connecticut, Colorado, Georgia, Tennessee, and Michigan require separation notices be sent to workers that list the reason for separation. The key reforms for these states involve ensuring that separation notices are submitted to the UI agency at the time of each job separation and that the forms use a standardized list of separation reasons rather than open-ended responses. Michigan, in particular, should strengthen its system by requiring employers to include the date of separation—its current notice allows employers to specify a reason but not the date.

All other states–43 and D.C–don’t have separation notices, but should adopt them. These are states that either require employers to provide a generic pamphlet to workers lacking details about their job separations, or do not require information to be provided to workers or the UI agency at the time of separation. However, 21 states—and the District of Columbia—already require employers to keep the reason for separation in their business records. Sharing this information directly with state UI agencies is a natural next step, allowing those agencies to make full use of data that employers are already required to collect.

Conclusion

One out of five improper payments could be avoided if UI agencies obtained timely and accurate separation information. Currently, this information is requested from employers after UI claims are submitted—a process that invites delays and errors. Canada’s model demonstrates that gathering separation information at the time of job separation, rather than weeks later, can reduce errors and improve benefit delivery.

Some states are partway there, with laws or regulations requiring separation notices that capture key details. But to be effective, these forms should be standardized, consistently submitted to UI agencies, and include the reason and date of separation. States that lack such notices should follow suit, adopting measures to ensure accurate separation information is collected promptly after workers leave their jobs.