Since 2000, the U.S. has offered noncitizen victims of serious crimes two visas — the T and U visas — to incentivize them to aid law enforcement in prosecuting dangerous criminals without fear of deportation. But the T visa — for trafficking victims — is rarely used and the U visa — for crime victims — is badly backlogged. It’s time for Congress to actively address the visas’ deficiencies to serve victims and law enforcement better and enhance public safety by recapturing the almost 40,000 unused T visas from the last decade and awarding them to approved, backlogged U visa applicants.

Both T and U nonimmigrant visas were created from the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. Qualified T visa applicants must have been victims of human trafficking, often sex and labor trafficking. Qualified U visa applicants must have suffered physical and mental abuse as victims of criminal activity, including human trafficking. While T visa applicants are eligible for the U visa, not all U visa applicants qualify for the T visa.

U visas and T visas are limited annually to 10,000 and 5,000, respectively. Family members of U and T visa applicants can be included in the petitions and are excluded from annual limits. U visas last four years, during which recipients can legally work. After three years in the U.S., U visa holders can apply for lawful permanent residency, a green card, if they have continued to assist in the prosecution of the crime associated with their petition.

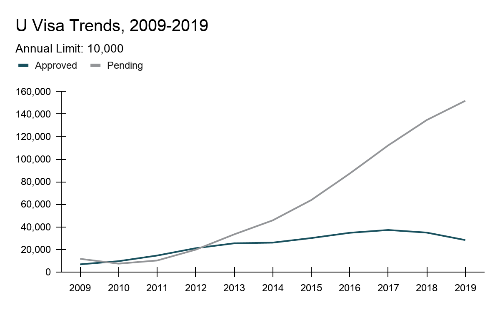

Since 2010, U visa approvals have reached the limit well before the end of each fiscal year. Regardless, new petitions are still processed so that applicants can get conditional work authorization — but the sizeable backlog remains. This means applicants wait four years just to receive conditional approval. But now, due to the severe accumulation of conditional approvals, verified applicants can expect to wait more than 15 years before receiving U nonimmigrant status.

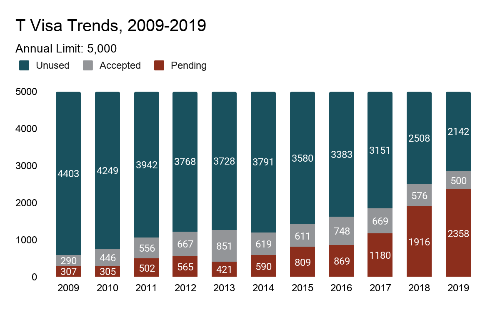

By contrast, T visas have been highly underutilized. Since 2010, fewer than 10 percent of the available visas have been awarded annually. Although the number of pending cases has grown quickly — especially in recent years — the total number of pending and approved cases consistently falls well below the annual limit. In 2019, over 1,200 cases were submitted and 500 cases were approved, while over 2,000 cases were pending.

Some may suggest that the T visa’s lower usage rate means Congress should lower the ceiling for the visa, but the data suggests that would be a poor response for several reasons.

More people are qualified for the T visa than the annual numbers suggest. Several factors impact their awareness of the program, and thus why it is underutilized.

Generally, many undocumented immigrants are afraid to contact law enforcement for fear of deportation, even when they have been victims of violence. Furthermore, many immigrants are not proficient in English and have difficulty communicating with the police when they seek protection.

In some cases, officers may be politically motivated against these victims or are unaware or misinformed about U and T visas. Eligible applicants who do work with law enforcement and are aware they qualify for T and U visas often find it challenging to convince the associated officers to sign certifications, obtain proof like police reports, and comply with requests for assistance with the visa petition. Police officers may also persuade these victims to drop charges against their abusers in domestic violence cases, compounding efforts to silence female victims made by abusive partners or employers and threats to have them deported.

Not only are refugees and asylees often unaware of the existence and specifics of the protective visas they qualify for, but so are those informing them about their options.

While these issues alone do not explain the complexity behind the low number of T visa applications or the overreliance on one known avenue, they demonstrate how combinations of factors deter qualified persons from petitioning for either visa.

The T and U visa petitioning system must be improved so that every noncitizen victim of abuse and trafficking seeks the help they need. The resulting increase in petitions would more realistically reflect how commonplace such crimes are and how important it is to make sure the justice system recognizes those crimes. Increasing awareness about T visas — especially among law enforcement and undocumented immigrant communities — would open pathways for progress.

The Immigrant Witness and Victim Protection Act of 2018 (H.R. 5058) and 2019 (H.R. 4319) would have addressed these issues by removing the U and T visas’ annual limits and providing work authorization for approved visa applicants within three months. Currently, applicants must pass a four-year vetting process before receiving such authorization.

President Biden has recently called for a bill that includes increasing the U visa annual limit to 30,000 and recapturing other visas. It’s a solid start but will not adequately ease the growing number of pending cases.

An immediate way to address the discrepancy is to reallocate unused T visas towards U visa petitions, thus partially alleviating the backlog. After all T visa pending applications are processed, over 38,000 unused visas could be utilized towards U visa applicants on conditional approval. Improving the U and T visa application process would make communities across the country safer due to increased trust among undocumented immigrants qualified for these visas and law enforcement.

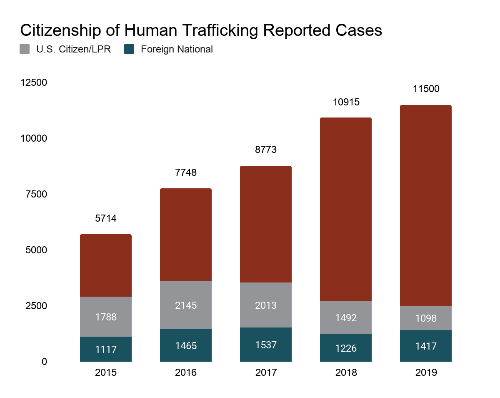

The number of foreign nationals reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline as victims grew an average of 10 percent between 2015 and 2019. Although the number of undocumented immigrants included in these statistics is unknown, these victims’ awareness of this hotline and the fact that they can call authorities for help will contribute to the fight against human trafficking rings.

Maintaining safety requires a community effort. That means ensuring that all community members can work with law enforcement — regardless of their status — which is vital for crime prevention and public safety. This minor tweak of recapturing previous years’ unused T visas to mitigate the U visa backlog would be an effective means for Congress to better protect victims.

A previous version of this piece misrepresented T visa trends and has been corrected.

Image by Larry White from Pixabay