In a new report from the Heritage Foundation, The State of Climate Science: No Justification for Extreme Policies, four policy analysts argue that the threat of climate change is exaggerated and that the costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions through public policy are prohibitively large. Given the source of the report (an institution that is perhaps the most influential think tank on the Right), and the paper’s ambition (a summary of the conservative case against climate action), it is well worth a close examination.

What we find, however, is a fragmentary acceptance and confused presentation of mainstream climate science and either an ignorance of—or a studied refusal to deal with—the strongest evidence for human influence on the climate. In that way, this report recalls the working paper from a group of scholars at the Cato Institute, The Case Against a Carbon Tax, which my colleague Jerry Taylor found failed to address or grapple with the strongest economic arguments for carbon taxes.

In this case, even a cursory reading of the primary literature on climate science would provide a very different picture than the one forwarded by Heritage. Alas, much of what the authors marshal to make their case are citations or references to blog posts, white papers from fellow conservative policy activists, and Congressional testimony from a handful of scientists who doubt the conclusions of mainstream climate science (and many of these resources offer arguments that either misread or are divorced from any reference to published literature).

Let’s consider some of the highlight conclusions of the Heritage paper.

Claim: There is no consensus about climate change

The Heritage authors reject the notion that a consensus around dangerous climate change exists:

“Broad agreement does exist, even among those labeled as skeptics, that the earth has warmed moderately over the past 60 years and that some portion of that warming can be attributed to carbon dioxide emissions… However, no consensus exists that man-made emissions are the primary driver of global warming or, more importantly, that global warming is accelerating and dangerous.”

That statement is flatly incorrect. It is one thing to argue that climate risk is not best measured by a show of hands. It is another to argue that the hand-count is something other than it actually is.

- As I recently wrote, the consensus among practicing climatologists says that most of the recent global warming (e.g. the about 1 °F increase in global temperatures since 1951) was caused by human activities. That degree of consensus seems robust across various survey methodologies and, critically, consensus gets stronger as expertise in the field increases.

- In its fifth assessment report, the IPCC attributed at least half of the warming between 1951-2010 to human activity. The best estimate was that all of the observed warming was caused by human activities.

- Published studies in peer-reviewed journals that quantify the amount of recent warming due to human factors overwhelmingly find that human influence has been the dominate driver of climate change in the last half century. If anything, natural factors favored global cooling over that period.

- A recent survey of economists who study the economics of climate change in the peer-reviewed literature finds that the median estimate of when climate change will negatively effect the economy is 2025. More than 75 percent believe that climate change will have a long-term negative effect on the growth rate of the economy. Fully 69 percent believe that the social cost of carbon emissions as estimated by the U.S. government is too low. And 93 percent believe that meaningful action to reduce CO2 emissions is warranted.

Given all that, there is room for debate on the details. How climate change will manifest itself is uncertain. Estimates of the economic costs of climate change, as in the social cost of carbon, vary widely. And the logical path from CO2 emissions to harms—from human dominance over the climate, to changing local environmental conditions, to impacts (positive and negative) on ecology and society—relies on reasoning over a series of uncertain propositions and understanding risk. But room for debate in the details does not challenge the fundamentals.

Claim: Future Warming is Not an Urgent Problem

The Heritage authors find “[n]o overwhelming consensus exists among climatologists on the magnitude of future warming or on the urgency to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.” But this claim is misleading and tells us far less than one might think. That’s because either of the assertions in the Heritage sentence requires assumptions or knowledge that is beyond the expertise of climatologists.

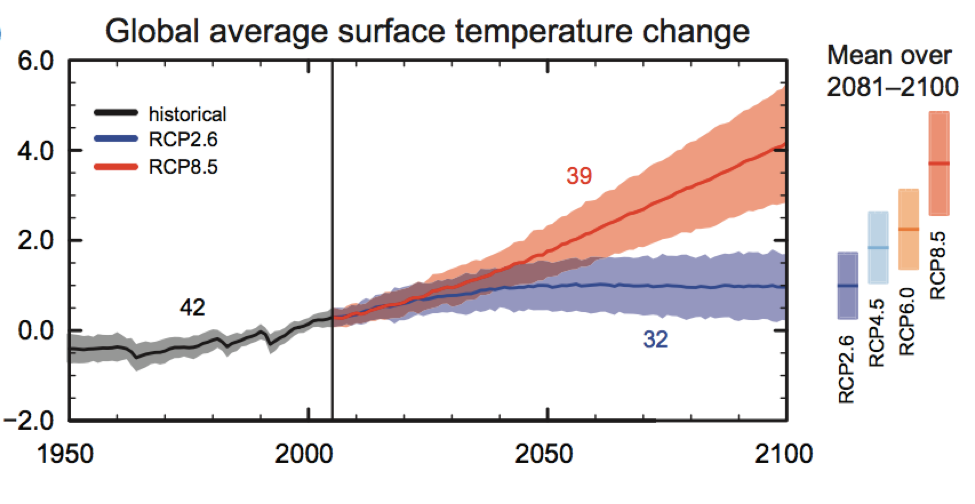

Estimating the magnitude of future warming, for instance, requires assumptions about future emissions of greenhouse gases (which depend on estimates regarding economic and technological development) and assumptions about future emissions reduction policies. When scenarios of such are provided—say, through the IPCC’s Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)—then the magnitude of future warming can be estimated using climate science.

Two such predictions are shown below, in degrees Celsius; one for a high CO2 world (RCP8.5) and one for a low CO2 world (RCP2.6). Each shaded area shows the range of predictions that come from the models submitted to the IPCC. As you can see, expectations about future emissions have a huge impact on the magnitude of future warming … and climatologists have no particular insight into which of those assumptions might prove more accurate in the decades down the road.

Image Source: IPCC AR5 Summary for Policymakers

The takeaway from the above figure is that climatologists can offer an extremely wide range of future warming estimates without disagreeing in any meaningful sense about the direct relationship between total greenhouse gas emissions and warming.

Likewise, the urgency to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is contingent upon the policy goal being sought. Climatologists, however, have no special insight as climatologists about whether one public policy goal is superior to another. It is when climate scientists are given a policy goal—such as limiting the increase in global average temperatures to less than 2 °C (3.6 °F)—that they can provide information. Because there is a robust relationship between the total amount of CO2 emitted since the industrial revolution and the future warming, climatologists can take any warming goal and translate that into a carbon budget; the amount of CO2 emissions that could still be released and maintain warming within the goal.

This spreadsheet from Carbon Brief shows the carbon budgets (referenced to IPCC numbers) implied by different warming thresholds in terms of present-day CO2 emissions. For a two-thirds chance of keeping warming below 2 °C, their calculations allow for a budget of 21 years of present day emissions. For a warming threshold of 3 °C, the budget is 56 years of present day emissions.

In sum, whether there is an urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is entirely dependent upon what our climate goals might be. Alas, Heritage does not directly (or even indirectly) address how much warming above pre-industrial levels we should continence as a matter of policy. Thus, their claim that there is no policy urgency is meaningless.

Claim: The climate models are wrong

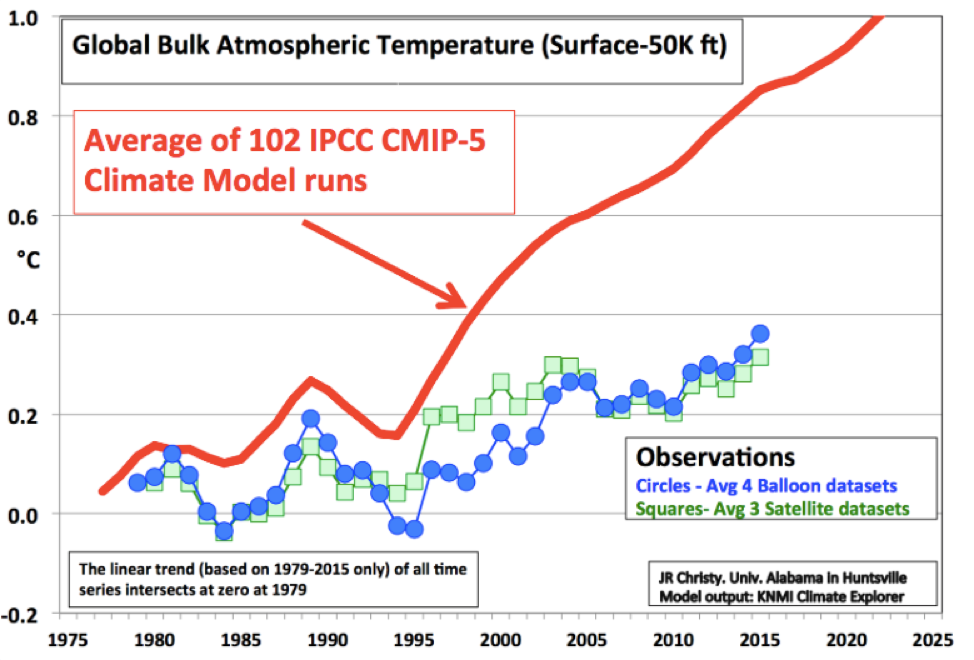

The Heritage paper spends some time assessing climate models versus measurements. Specifically, it embraces the comparison, oft forwarded by John Christy of the University of Alabama, between climate model simulations of temperatures in the troposphere (as measured by satellites and weather balloons) and those simulated by climate models. The graph looks like this.

Source: Congressional Testimony of Dr. John Christy, February 2, 2016

The Heritage report draws the following conclusion from that figure: “[m]any errors could account for the failure of the models to predict actual temperatures accurately. One that is widely suspect—equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS)—lies at the heart of the process.” Not all scientists agree with Dr. Christy’s graphical design, but there is divergence between models and data in tropospheric warming. As I have explained in a previous blog post, however, there are two problems with drawing conclusions about climate sensitivity from this comparison. First, it assumes away multi-decadal variability of the climate that is not related to climate change. Second, it neglects known errors in the simulations performed for the IPCC report. Though equilibrium climate sensitivity (defined as the long run temperature increase after doubling atmospheric CO2) is uncertain and could indeed be too high in the average climate model, it is not at all clear whether equilibrium climate sensitivity explains the discrepancy between atmospheric observations and computer simulations.

Regarding equilibrium climate sensitivity, Heritage claims that “recent peer-reviewed literature estimates that the equilibrium climate sensitivity is about two degrees Celsius, much lower than the IPCC’s assumed ECS of 3.0 degrees.” An ECS estimate of two degrees Celsius is on the lower end of generally accepted values (1.5 – 4.5°C). But contrary to what the authors are implying here, the most recent work in the literature does not definitively add weight to the low-ECS argument. Moreover, new analyses shows that many of the recent prominent papers reporting low estimates may have used biased methodology that favors low values. Once those biases are accounted for in that new study, ECS estimates of 2°C increase to 3°C.

But even if climate sensitivity is low, it does nothing to support the broader conclusion, forwarded by the Heritage paper, that climate science offers no view on the “urgency to reduce CO2 emissions.” A low-end climate sensitivity only reduces the warming expected from CO2 emissions and buys time, on the order of decades, to achieve emissions reductions necessary to meet temperature targets that have been adopted by the UNFCCC.

Claim: Present day temperature variations are not unprecedented

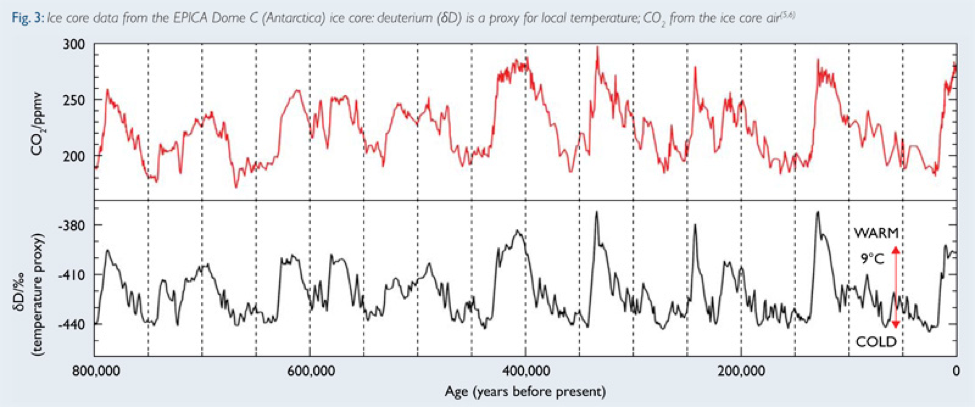

The Heritage paper cites the temperature records from ice cores, which show wild temperature variations (on the order of 10 °F) in the past as the world transitioned in and out of ice ages, and previous warm periods, like Medieval Warm Period. The point the authors labor to make here is that the climate has changed dramatically in the past, way before human activity could have influenced the changes and many different factors contribute to those changes. For the Heritage authors, that appears to open the question of what has been driving recent changes.

However, that natural forces drove climate change in the past says nothing about why climate is changing now. Different forces act to change the climate on timescales from years to millennia. Our understanding of what drove warming in the past actually reinforces the conclusion that human emissions are driving climate change today.

The Heritage report does not show, as I do below, the CO2 changes (red) that accompany the temperature proxy record (black) from Antarctic ice cores. While the CO2 changes that we observe in ice cores do not appear to instigate the large temperature shifts in the deep past (a complicated scientific question discussed in this book fromPaleoclimate expert Michael Bender), they do appear to contribute to warming as the climate exits ice ages.

Source: British Antarctic Survey

It works like this. Changes in the orbit of the Earth about the sun are thought to instigate the transition out of ice ages. As the northern hemisphere turns toward the sun during an ice age, the great ice sheets begin to melt and reflect less sunlight back to space (which has a warming effect on the global climate). As the climate warms, CO2 is released from the ocean into the atmosphere, which contributes to additional warming.

The cycles of glacial and interglacial climate states provide clues about how sensitive the climate is to increasing CO2. That’s because scientists can account for the warming and cooling effects of other factors. Looking even further back than the last 1 million years, a temperature records from the past 65 million years indicate that equilibrium climate sensitivity should fall in the range of 2.2 – 4.8 °C.

So rather than showing that large climate variability (say, greater than 1°C on century timescales) should be expected from random factors outside human control, the long-term records indicate that specific factors act to change the climate over long periods and that CO2 has played a substantial role in the climate changes of the past. Why would it not do the same as we add it to the atmosphere now?

Claim: Present day sea level rise is insignificant compared to geological history

The Heritage report argues that even the worst predictions of sea level rise over the next century are small compared to the 400-foot rise that accompanied the end of the last ice age. IPCC estimates top out near 3 feet in the 21st century (meaning a high emissions scenario is met with a large response in sea level, but melting ice sheets could add more under a worst case scenario). So numerically Heritage is correct, but it says little about the damages we can expect from sea level rise.

The Heritage report also misses how confidently recent sea level rise can be attributed to human activity. Of recent sea level rise, it claims (without citation) that “[c]orresponding to the recovery from the little ice age, sea level has risen about eight inches in the past 130 years. During this period, the rate of this rise has varied on multidecadal time scales making identifying exact reasons behind upswings, such has been observed over the past few decades, difficult.”

Meanwhile, as my colleague Thomas Cropper wrote recently, new estimates from the literature show that 37±38 percent of sea level rise between 1900-2005 was attributable to human influence on the climate. But for the later part of the 20th century (1970-2005), human influence accounts for 69±31% of measured sea level rise. And as Cropper notes, human CO2 emissions are expected to drive sea level rise for thousands of years into the future. Modeling shows fast emissions reductions in the next few decades could reduce the eventual rise by up to 80 feet compared to high emissions scenarios. So while the climate may respond slowly, the human influence on the climate is geological in scale.

Conclusion

The whole of the Heritage argument about climate science seems to be that the changes we have seen are small and we don’t yet understand the drivers of latter-day climate change. Therefore, we should not seek—nor can we understand—the effects of emissions reductions. This argument is fundamentally wrong.

Yes, there is uncertainty in projections of any given scenario of future CO2 emissions. There is likewise substantial uncertainty about how much the various risks to society increase with temperature. But the fundamental relationships between increased CO2 and warming (the human influence on the climate)—then sea level rise and changes in weather—are robust.

I agree that not all of the arguments made by the Obama Administration, the Left, and environmentalists for action are compelling (c.f. public health). I also agree with the authors that the state of climate science does not warrant extreme policies. But while we know climate action has costs, so too does inaction. As my colleague Jerry Taylor recently argued, given what we know about climate risk, present regulatory and market interventions are far too feeble to achieve significant climate gains. By rejecting the case for any action outright because of unwarranted doubts about the science, Heritage (and other conservatives) forgo the opportunity to lessen the cost or increase the efficacy of policies for climate action.

Image by qimono from Pixabay Stock.