Key takeaways:

- Successful program modernization and integrity efforts for the administration of unemployment insurance require steady financing to build up essential internal capacity. Yet, the congressional appropriations for UI administration are largely based on workload projections that provide state agencies barebone resources. Not enough funding is provided to build up key competencies.

- There has been a 27 percent decline in the value of the administrative allocations that states must plan around since the mid-2000s when adjusting for inflation. States’ allocations fluctuate from year to year, making it difficult to make long-term plans and hire requisite staff.

- At the end of fiscal years, funds not appropriated for state administration are often transferred to the account for emergency benefits. This is the case even though a 20 percent share of the federal unemployment tax funds is already being set aside for that purpose.

- The current funding dynamics result in Central and Southeast states getting the lowest proportion of funds returned for program administration relative to what was raised in-state. These states must manage their programs with half as many dollars per working-age resident as the most well-funded state agencies receive.

- We recommend better coupling between what is raised for UI program administration and what goes back to states. Furthermore, the funding stream itself must become more steady and generous to ensure all states can properly invest in their programs.

Introduction

Maintenance costs are frustrating to deal with, but leaving smaller issues unaddressed makes you vulnerable to more serious problems down the line. If you don’t fix the leaky roof in a timely manner, standard rain can cause mold to develop, while a major storm could leave you with widespread damage across the house. The cumulative cost is far more expensive than if you had just paid to keep the roof in working condition.

The past several decades of unemployment insurance (UI) administration financing look a lot like delayed home maintenance. The federal government is primarily responsible for funding UI program administration, yet it has not provided state agencies with the necessary funding to fix “leaks.” Legitimate applicants struggle to maneuver complicated applications and outdated sites, while the state agencies themselves often cannot process the claims efficiently nor keep the programs secure from fraud. Solvable shortcomings, neglected due to the poor administrative financing, have snowballed into structural flaws that hurt American workers when they need UI benefits most, make states vulnerable to substantial fraud, and can cause the whole system (the “house”) to collapse.

This paper identifies where UI administration financing is going wrong and explains how to improve the process so that state administrators consistently have the resources they need to get benefits out the door quickly and to the right people. The current formula generally only allocates enough funds to UI agencies to cover the basic costs of managing claims and distributing the benefits. Moreover, the true value of those base allocations has shrunk over time. Congress has made insufficient funds available for regular program upkeep and repair. Although states have been impacted to varying degrees, all have suffered from the current model. For UI agencies to be able to maximize program efficiency and integrity, reforms must (1) strengthen the overall administrative funding stream and (2) simplify the funding process so that more dollars raised for administration end up in state accounts.

Fix funding to improve integrity

Congress has largely viewed recent UI administration collapses as a series of technical failures. In response to the well-publicized struggles of state agencies to keep up with claims during the pandemic, federal lawmakers appropriated $2 billion to implement upgrades ($1 billion was later cut from this total). States have used these funds to expand their use of data verification systems, simplify the language used on the claims sites, and even automate some work.1 Each of these updates is beneficial. However, the job is not done. Congress still must fix the core problem holding back states from secure, functional systems: chronic administration underfunding.2

Successful program modernization and integrity efforts require steady financing to build up essential internal capacity. “There’s no ‘silver bullet’ to completely eradicate fraud from our benefits systems,” New Jersey Labor Commissioner Robert Asaro-Angelo told a House committee last fall, “but, we can combat it in every way possible” by “continually learning and training so we stay one step ahead.”3 Niskanen Senior Fellow Jennifer Pahlka documents this reality in her book, Recoding America.4 “Big-ticket” technology purchases are often tempting to policymakers, yet these one-time overhauls have a limited impact when the agencies themselves are not capable of adapting the systems over time.5 A robust, skilled staff is as essential as new technology, if not more so, to ensure those tools are properly used and the right ones continue to be added over time.

Yet, the UI administration financing system as structured prohibits agencies from maintaining the necessary workforce and proficiencies. According to the Government Accountability Office, outdated methods for assessing state needs each year “consistently left states underfunded, which contributed to them not being prepared for the surge in claims from the pandemic.”6 Likewise, Department of Labor officials have pointed out that the “long-term neglect to adequately fund the UI system” and the absence of a “dedicated funding stream for maintaining and enhancing the information technology systems that underpin state UI operations” were major reasons why states could not counter fraudulent operations during the pandemic.7 UI agencies forfeit key competencies because of the weak annual allocations and will continue to underperform until administrative financing is reformed.

Background

First established in 1935 as part of the Social Security Act, the unemployment insurance system is the product of an ongoing federal-state partnership.8 States are responsible for funding the regular benefits sent out to claimants with state taxes, while the federal government takes on a greater financial role for the emergency benefit programs in place during times of high unemployment. Each state manages its own UI program, and the federal government covers the associated administrative costs, generally with revenue raised with the federal unemployment tax (colloquially called FUTA, after the Federal Unemployment Tax Act).

Weaknesses with unemployment insurance administration have received substantial attention since the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic. State UI agencies did their best but struggled to handle the surge in unemployment claims, manage the set-up of emergency federal benefits, and maintain program integrity. As a result, legitimate claimants could not easily access their benefits, while criminals took advantage of the situation and likely made off with north of $100 billion.9 While the direct factors enabling this enormous fraud were weak interstate coordination and verification measures, those failures were rooted in decades of inadequate and unstable investment.10

The inflation-adjusted value of the resources provided annually to states for managing their unemployment programs has declined substantially over time, even as agencies must process benefits claims for growing working-age populations. Sudden bursts of funds, like those doled out in response to Covid-19, are unreliable and insufficient to sustain long-term strategies and solutions. Without more standard funding each year, states will struggle to continue to add security measures, improve accessibility, and make benefit processing more efficient.

Not only are the state allocations too small — they are also variable, which impedes forward-thinking investments and creates fragile systems. The process through which the overall national allocation for UI administration and the respective state base-funding get determined deserves a lot of blame for this dynamic. In particular, fewer administrative dollars are distributed to states when fewer claims are expected, meaning that UI agencies often receive fewer resources precisely when they have greater bandwidth to pursue upgrades. The alternative approach state policymakers then lean on when the accrued problems become visible — making “big ticket” expenditures to overhaul the administrative system — tends to produce flawed program infrastructure.

Crucially, the solution here is not just to raise more money, but to ensure that money goes to its intended use. In an average year, only some of the revenue raised via the so-called FUTA tax that was originally intended for administration is actually allocated for that purpose. Since the mid-2000s, most agencies only received back a portion of the tax dollars raised in each state explicitly for program administration, with Central and Southeast U.S. states seeing the worst returns. Those state agencies often face the consequences of a self-reinforcing cycle – states with low benefit recipiency proceed to get less overall administrative funding that could help improve program access.

Statutory accounting provisions reinforce the decoupling of revenue and allocation amounts. The federal government controls the funds meant for administration in a specific account, called the Employment Security Administration Account (ESAA), which frequently is required to have its balance adjusted downward at the conclusion of fiscal years. Billions of tax dollars deposited in ESAA for administration get transferred away and are instead set aside for emergency unemployment benefits due to the account balance limits.

States would benefit from a tighter coupling between the amount raised for administration and what gets returned to them. Yet, the current revenue generated cannot make up for the entire administrative allocation value that has been lost over time nor handle the costliest years of implementation. Resolving the financing problem will require both streamlining the distribution of the funds raised and making that revenue stream more robust by increasing the FUTA taxable wage base.

The remainder of the paper details the UI administration financing system and possible fixes. The first section explains each step of the general funding process. The second section analyzes key consequences of the existing funding structure. The final section lays out several reform options for fixing funding to improve program integrity.

The general administrative funding process

Raising federal funds for state administration

The FUTA tax raises the revenue that funds UI administration. This tax, which is levied on employers, applies to the first $7,000 of each employee’s wages at a 6 percent rate. Businesses receive a 5.4 percent credit against that tax, assuming the employer and the state comply with federal rules, which means the actual tax rate is 0.6 percent.11 Since most workers earn wages exceeding $7,000, it is effectively a $42 charge per employee.

The taxable wage base has remained at $7,000 since 1982, reducing the value of the FUTA tax over time as price levels increase.12 Unless the FUTA wage base adjusts for inflation like other components of the tax code, it will continue eroding. For comparison, Social Security’s taxable wage base is pegged to grow in line with an index of average wages.13 As a result, it has increased by $130,000 since Congress last adjusted the UI taxable wage base.14 The median wage has also more than quadrupled since then, which has increased the relative share of the FUTA burden borne by lower-income workers and their employers. 15

Employers may see their FUTA obligations increase when their state’s program has unpaid loans owed to the federal government over consecutive years (as of January 1). This has occurred after recessions, when states needed to borrow funds to cover the payment of regular benefit claims. The business credit is reduced by 0.3 percentage points each year a state loan balance goes unpaid.16 Weak state UI benefit financing, a separate but connected issue, is often to blame.

California is a prime example of a state struggling with UI debt now. The state owed almost $20 billion to the federal government in UI loans following the pandemic due to its weak taxable wage base for regular UI benefits.17 It could take close to a decade to pay them off. Notably, California took until 2018 to pay off the loans owed from the Great Recession and entered 2020 with a weak trust fund balance, forcing it back into debt when the next crisis hit.18,19 California businesses can expect their net FUTA tax rate to increase — they will owe double what an equivalent company in a solvent state must contribute per employee in 2024 — until the state pays the debt back in full.20 If the state government fails to cover interest payments on the loans, California businesses cannot receive any portion of their 5.4 percent credit, nor can the state receive administrative grants.

Where the FUTA funds are deposited

Funds raised via the FUTA tax are deposited periodically into the federal Employment Security Administration Account (the account will be referred to as the Administration Account starting here). The money management gets more complicated from here.21

Twenty percent of the FUTA funds deposited each month into the Administration Account are subsequently transferred to the Extended Unemployment Compensation Account (its acronym is EUCA but it will be referred to as the Extended Benefits Account), which holds funds that finance the federal government’s share of Extended Benefits, additional weeks of benefits that activate when unemployment is high. The remaining 80 percent of FUTA funds placed in the Administration Account are used primarily for UI administration (and implementing a handful of Labor Department and veterans employment programs), with most of the funds being transferred to state UI accounts.

However, as discussed below, the transfer of these funds to states for administration is not automatic. Congress must appropriate those funds and generally doles out less than was raised in strong economic years. The opposite is true during recessions and the subsequent recovery years— the total allocations sent to states typically exceed the FUTA funds placed in the Administration Account for program management. These economic dynamics and statutory provisions for the account triggered at the completion of a fiscal year influence the Administration Account balance.

Map of where FUTA funds generally get directed

If the Administration Account end-of-year balance exceeds 40 percent of the prior fiscal year administrative appropriations, the statute governing the account requires the “excess” funds to be transferred to the Extended Benefits Account (in other words, the Extended Benefits Account sometimes gets a double dip from the Administration Account).22 This transfer requirement is frequently activated in stronger economic years when administrative allocations are smaller. An exception to the law is that any outstanding obligations included in the balance are kept in the Administration Account going into the next year. The Administration Account balance may appear to break the 40 percent rule when the excess funds are already designated. In recovery years, there are a lot of unpaid obligations to sort out, meaning that the Administration Account balance may stay above the 40 percent marker for a series of years. The Administration Account balance remained high after the Great Recession and could again in the coming years as agencies resolve Covid-era obligations.

Administrative allocations

The administrative allocations for states are determined independently from the amount raised with the FUTA tax, resulting in a disconnect between the two. Actuarial projections for the national workload of a given fiscal year inform the budget request brought before Congress, which has discretion over the spending.23 Lawmakers make that decision informed by the projected workload facing states and the level of prioritization that UI administration receives compared to other budget items. Congress approves fewer national base dollars when fewer overall claims are expected. At the same time, individual states with previously low workloads tend to receive low workload projections, which leads to weaker base allocation amounts. State agencies must plan their years according to the base funds received, since only those dollars are guaranteed.24

Additional administrative funds are made available on a quarterly basis if the national workload exceeds the projected average weekly insured unemployment claims.25 Yet, when a state experiences more claims than expected while the national workload meets expectations, the state must supply additional administrative funds unless Congress decides to pass more funding for them.26

Little to no funding is allotted by Congress for the specific purpose of improving administration. States can sometimes submit supplemental budget requests for certain integrity or performance measures if unused fiscal year money becomes available. But those funds come with distinct obligations and are not always granted. Furthermore, one-off funding can only do so much. States have been largely unable to hire agency staff with American Rescue Plan funds who could work on continuous program improvements because the funding was only temporary.

Although the annual congressional budget requests have reflected changes to the projected workload, insufficient adjustments have been made for various processing and salary factors and for inflation. States are now more efficient with tasks, while salary levels have increased. These factors partially offset each other, but the collective cost burden has gone up. States must battle over a confined and shrinking pool of resources. Recent fiscal year congressional budget requests have updated the processing and salary considerations to more accurately reflect the levels reported by states, resulting in approximately a $400 million net increase.27 However, the finalized budgets have not entirely covered these requests.28

In order to determine how the administrative funds get distributed amongst states, UI agencies must submit information about their programs as part of the Resource Justification Model, which utilizes the base national workload projections. Across six categories of work — initial claims, non-monetary determinations, appeals, weeks claimed, wage records, and tax — states detail how much time is required to complete each type of task and the corresponding salary rates.29 The minutes-per-unit (MPU) spent on each category task gets multiplied by the state salary rates and the estimated state workloads from the national projections to determine the total base amounts requested by states.30

The collective amount requested by the states consistently exceeds the Congressional appropriations, which are determined separately. The amount budgeted for the states must then be revised downward to meet the approved national funding level.31 State MPUs are ordered from highest to lowest in each work category. The 10 most efficient programs in each work category do not experience an MPU reduction, while the 43 other programs face a decrease. Each state receives funding equal to the cumulative values determined across the six categories with the adjusted MPUs.

Allocation disparities among states arise from the projected state workloads (discussed above) and these MPU calculations. UI agencies need funds to manage their programs for the entire state worker population and to keep the systems ready for economic downturns. But when a program is difficult to access and struggles to process claims, the Resource Justification Model leads to the state getting even fewer resources than necessary for the overall population it oversees. This low funding makes it harder to address administrative issues and makes state programs more vulnerable when a crisis hits.

Consequences of the current funding structure

The erosion of administrative support

UI agencies have begun implementing more protections to secure their systems but may struggle to continue reinforcing program integrity. Every state now agrees to use the national Integrity Data Hub when verifying claims.32 Additional ID verification enhancements cost states money, though, and Congress has not approved recent budget requests to account for these expenses. This funding gap was of less concern when American Rescue Plan funds were available, but warrants greater attention moving forward given the ongoing costs.

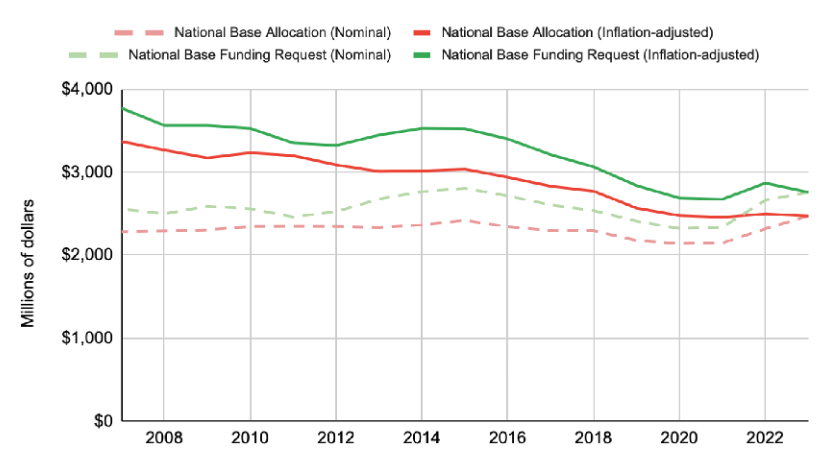

States have consistently needed to perform all their basic program duties plus enhance program integrity with less. Base administration allocations have not kept up with inflation. While the overall base funding distributed to states has grown by about $200 million from fiscal year 2007 to 2023, states have actually seen their inflation-adjusted base administrative funding reduced by $900 million over this period, a 27 percent decline.33 Even states’ base national funding request, which the national workload projection informs, has experienced diminishing real value and that shrinking ask does not get fully covered by Congress (see Figure #2).34

Base funding sent out to states for UI administration

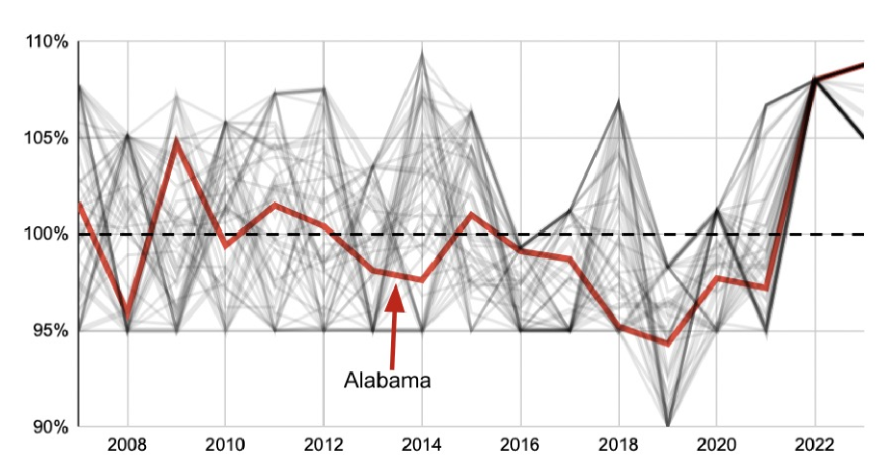

The picture gets even bleaker when looking at the state-specific base allocations over time. States constantly see their base allocations jump above and below the amounts provided in the preceding year. The figure below presents this inconsistency, displaying state allocations as a percentage of the prior fiscal year amount. Alabama’s allocation levels are shown in red as an example, while every other state is presented in gray.

States’ base UI administrative funding as a % of prior year base allocation

Alabama’s trajectory showcases the inconsistent funding seen across all the states. Over the past decade and a half, Alabama has seen its base allocation for UI administration decline from the previous year more times than it has increased. Other states experienced similar funding fluctuations over time, as reflected in Figure 3.

The consequences of such variable funding look quite clear in hindsight. States collectively had their worst overall base funding year in 2019 due to the low expected workload. Instead of being able to take advantage of lower claims levels and focus more resources on various integrity measures during what ended up being the lead-up to the Covid-19 pandemic, every state saw its base funding cut. And unlike past fiscal years where the base allocations could not drop more than 5 percent, the 2019 amounts could drop 10 percent from the prior year’s level.35

Every state has received better administrative funding in the last several years because specific provisions were approved that guaranteed increases.36 Nevertheless, those improvements fail to cover the real value of the state allocations lost over time. Twenty states have seen their administrative funding fall over 30 percent below their 2006 allocations when adjusting for inflation. Wyoming is the only state that has seen its current allocation remain within 10 percent of its 2006 inflation-adjusted amount, and even it has experienced a decline (seen in Figure 4).

2023 base allocations as a proportion of 2006 inflation-adjusted amounts

To make matters worse, even the nominal allocation levels have not kept pace with working-age (18-64) population growth in more than two-thirds of states.37 States may have low applicant levels due to flawed administrative systems, while the true working populations in need of support have grown. By allocating funds according to workload projections and not adequately adjusting for price and population increases, the federal government ensures a wide range of states — California, Massachusetts, Georgia, Arkansas, Montana, and Ohio, to name a handful — get just three-quarters of the resources they used to receive earlier in the century to implement their programs (seen in Figure 5).

2022 base allocations per capita (Aged 18-64) as a proportion of 2006 inflation-adjusted amounts

Note: Data limitations with the population adjustments required use of the 2022 numbers rather than 2023.

Central and Southeast states tend to receive the least support in terms of dollars per working-age resident. They must implement their UI programs for under $10 per working-age resident, while states in other regions widely receive above $10. In 2022, Central and Southeast states generally had to implement their UI programs with half as many dollars per working-age resident than New Jersey, a state lauded for recent program improvements enacted under existing funding levels (seen in Figure 6).

States cannot easily implement systematic upgrades and hire the necessary staff when they aren’t guaranteed consistent or sufficient funding year-to-year. Technology improvement costs do not vary as much between states as other administrative functions and must receive diligent attention. Until states are assured more reliable and robust allocations, they will not invest enough resources to solidify program implementation and continue bulking up post-Covid anti-fraud protections.

2022 base allocations per capita (Aged 18-64)

Note: Data limitations with the population adjustments required use of the 2022 numbers rather than 2023.

The tax revenue-allocation disconnect

The disconnect between what gets raised for administration and what the federal government distributes helps to explain why state programs have struggled to make improvements. FUTA tax revenue deposited in the Administrative Account (ESAA) specifically for administration is not ending up in state agencies’ accounts. Since 2006, a total of $6.4 billion originally meant for program administration that did not get used for that purpose.38 This amount translates to an average fiscal year gap of +$370 million between what gets raised via the FUTA tax and what has been either deposited automatically for future Extended Benefits payments (i.e., the 20 percent share going to the Extended Benefits Account) or distributed out for administrative tasks.

When the economy struggles, administrative costs typically increase as revenue declines. As the United States recovered from the Great Recession in the early 2010s, administrative expenses exceeded the raised revenue by hundreds of millions of dollars. This dynamic was true to an even greater degree during the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in temporary spending deficits. Raising more funds annually by expanding the FUTA taxable wage base would help prevent shortfalls in the costliest years and is a crucial component of any financing reforms. However, it is similarly crucial to consider how applying surplus funds for administrative improvements in strong economic years could help limit the costs when recessions hit.

Table 1. Flow of FUTA funds reflected in the President’s Unemployment Insurance Program Outlook, in billions

Additional funding was sent out to states to implement temporary pandemic federal benefits and help manage the higher claims numbers. But this support arrived years too late. States needed consistent support for administrative upgrades over time, not a surge of funding after a crisis arrived.39 Quality improvements that would have helped facilitate efficient processing and protect system integrity simply could not be enacted in such a short period while under the duress of a large claims load. The result was costly administration and a lot of waste.

Unallocated dollars deposited in the Administrative Account could have been used to implement upgrades across state programs in preparation for a crisis like Covid-19. In the five fiscal years prior to the pandemic, there was a surplus of $4.6 billion raised via FUTA taxes for administration but not allocated for such purposes. That is nearly the same amount of Administration Account funds initially meant for administration — $4.82 billion — that were instead transferred to the Extended Benefits Account for Extended Benefits payments, because the 40 percent threshold provisions for the Administration Account were triggered.40 Extended Benefits payments play an important role but should not be pitted against fully funding program administration.

The primary purpose of FUTA taxes should be to fund program administration, but accounting rules and discretionary appropriation practices are inhibiting this function. As a result, the vast majority of states are seeing only a portion of the FUTA funds raised in the state for administration returned for that purpose. Only around a dozen states have gotten back their tax contributions deposited in the Administrative Account for administration over the last couple decades, while the remaining states have been forced to implement their programs with a fraction of the administrative funds each has raised. Central and Southeast states have seen the worst returns (Figure 7).

Proportion of funds deposited in ESAA for administration by states that were returned to them over the past two decades

Diverting billions of funds away from administration was inadvisable for years and is not a tenable approach moving forward. Over a third of the real decline in base allocations could be resolved by taking full advantage of all the funds deposited in the Administration Account for program management. Furthermore, states seeing the smallest shares of FUTA funds returned for administration could get larger allocations. Better funding alone won’t eliminate all the issues facing UI programs across the country, but it will enable states to maximize program integrity and overall performance with guidance41 from the DOL.

How to simplify and strengthen administrative allocations

UI administration financing rules are too complex and impede full use of the federal funds raised. In order to better support state administration, policymakers must simplify the financing process and make it more robust. Congress should ensure that state administrative allocations are based on the FUTA funds raised in each state. The 80 percent share of FUTA taxes deposited in the Administrative Account (ESAA) for program administration should be dedicated to that purpose. Additionally, more FUTA funds must also be raised by increasing the taxable wage base to ensure all states receive sufficient resources.

Let states work with what they raise

The pipeline connecting the FUTA taxes raised and what funds go back to states is broken and diverts too much funding elsewhere. Twenty percent of FUTA funds should continue going to the Extended Benefits Account for Extended Benefits payments, but the other 80 percent should be fully applied to program administration. Billions of dollars that are placed in the Administration Account — not the 20 percent share automatically set aside for Extended Benefits — could be used to improve anti-fraud protections and claims processing speeds, but are not ending up in state hands.

In order for 80 percent of FUTA funds to go towards administration, policymakers should eliminate the 40 percent threshold provisions for the Administrative Account that force funds to transfer over to the Extended Benefits account. The Extended Benefits account will continue to receive 20 percent of FUTA funds, but the remainder should be safe in the Administrative Account and used solely for program administration. If policymakers are to guarantee proper investments in UI administration, they cannot allow the Extended Benefits account to continue double-dipping from the FUTA funds.

How FUTA funds could be utilized

Likewise, policymakers should reform the current allocation process. The national administrative funding and state-level allocations should not be made according to projected workloads and resource justifications. These parts of the process are unnecessarily complicated and lead to chronic underinvestment: Funding is unnecessarily tightened when states have the best capacity to make program improvements, and the UI agencies most in need of resources are frequently shortchanged. States simply cannot invest in the requisite staff to improve the system over time under this financial model.

Instead, the FUTA taxes raised in a state for its program administration should be returned to that state. The net effect would be to apply hundreds of millions more dollars in an average year for administration, with many states with the weakest funding per working-age resident seeing the biggest returns.

Increase the amount of FUTA funds for administration

Simplifying the FUTA tax-to-state UI account pipeline only resolves a part of the problem. The real value of the base administrative allocations has eroded substantially at the same time that states have accrued larger working-age populations. Policymakers must fully replenish the administration funding levels, and unallocated funds will only make up part of the loss.

If the funding level provided to states for base administration is to match the real value of the FY 2006 base allocations, another $900 million will be required annually, bringing the baseline amount states work with up to $3.4 billion. Congress could then index that amount for inflation moving forward.

Policymakers should also consider what amount of funding per working-age resident could enable states to pursue the most integrity and performance enhancements over time. New Jersey’s UI program has been a model of success over the last few years, having brought in a team of experts to improve administration and the agency itself.42 If other states are to implement upgrades like New Jersey, Congress must provide more predictable annual technology funding and overall resources per working-age resident. This includes considering converting the UI administrative appropriation structure into per-capita block grants.

In 2022, New Jersey received $18.58 per working-age resident for base UI administration, the seventh highest U.S. rate. Thirty-six states were at rates at least $5 lower than New Jersey; twenty-one of those states received under $10 per working-age resident. This disparity is partially because more workers in New Jersey apply for and receive benefits relative to the population size of the state. If every state got $18.58 in UI administrative funding for each working-age resident, the national base administration funding level would have been $3.81 billion rather than $2.32 billion.

To raise the requisite funds, policymakers should finally fix the FUTA taxable wage base, which has remained at $7,000 since the early ‘80s. Over two thirds of the wage base value has been lost when adjusting for inflation — a similar issue to the administrative allocation erosion, but on the financing side. Updating the FUTA wage base for inflation, or rising wages, is a necessary step forward.43 As the Congressional Budget Office has indicated, doubling the wage base from the first $7,000 to $14,000 and indexing it to inflation would generate more than enough administrative funding for all states.44

Conclusion

The challenges facing state unemployment insurance agencies, highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic, reveal the urgent need for reforms in UI administrative financing. States require additional funds to make up for the lost real value of their allocations, year-to-year fluctuations that impede planning, and growing working-age populations. Unreliable base allocations have inhibited states from hiring staff who can incrementally improve their programs, forcing them to rely on infrequent, “big push” overhauls that have failed to meet expectations. The result has often been subpar program performance.

UI administration funding levels should be adjusted for inflation, and states should receive adequate dollars per working-age resident to run their programs. New Jersey has implemented a range of improvements over the past several years with its existing base funding per working-age resident. Other state UI agencies should receive the same funding rate to emulate the Garden State’s approach.

The disconnect between the FUTA dollars raised and the amounts appropriated to states, coupled with the Administration Account balance requirement that redirects funds away from their initial purpose, reinforces the administrative underfunding. In order for states to make continuous, long-term investments in their UI programs, policymakers must streamline the distribution process of FUTA funds. This overhaul should include ending use of (1) the relevant statutory provisions that establish the 40 percent threshold requirement for the Administration Account and (2) national workload projections and the Resource Justification Model for determining the funding amounts distributed to states. A greater proportion of FUTA funds raised in a state must be returned to it for UI administration.

By addressing these fundamental issues in UI administrative financing, policymakers can help build a more resilient and responsive unemployment insurance system that better serves claimants, effectively stops fraud, and contributes to economic dynamism and growth.

Footnotes

- U.S. Department of Labor, Insights and Successes: American Rescue Plan Act Investments in Unemployment Insurance Modernization (Washington, D.C.: January, 2023). ↩︎

- Marta Lachowska, Alexandre Mas, & Stephen A. Woodbury. Poor Performance as a Predictable Outcome: Financing the Administration of Unemployment Insurance. AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 112 (May, 2022): 102-106. ↩︎

- Testimony from New Jersey Labor Commission on Fraud Prevention, Before the U.S. House Ways & Means Oversight Subcommittee, 118th Congress (2023) (Testimony by Robert Asaro-Angelo, New Jersey Department of Labor Commissioner). ↩︎

- Jennifer Pahlka, Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better (Henry Holt and Co., 2023). ↩︎

- Jennifer Pahlka, “Better government tech starts with people. New Jersey shows how.,” The Washington Post, June 13, 2023. ↩︎

- U.S. Government Accountability Office, Unemployment Insurance: Transformation Needed to Address Program Design, Infrastructure, and Integrity Risks, GAO-22-105162 (Washington, D.C.: June 1, 2022). ↩︎

- U.S. Government Accountability Office, Unemployment Insurance: Estimated Amount of Fraud During Pandemic Likely Between $100 Billion and $135 Billion, GAO-23-106696 (Washington, D.C.: September 12, 2023). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Directors’ Guide: Essential Information for Unemployment Insurance (UI) Directors (Washington, D.C.: March, 2020).; Internal Revenue Service, FUTA Credit Reduction (Washington, D.C.: April 3, 2024). ↩︎

- U.S. Government Accountability Office, Estimated Amount of Fraud During Pandemic Likely Between $100 Billion and $135 Billion. ↩︎

- Matt Darling, What Star Wars can teach us about unemployment insurance fraud(Washington D.C.: Niskanen Center, April 11, 2023).; Angela Hanks, “Encouragement for States to Use the Integrity Data Hub (IDH) available through the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Integrity Center” (Washington D.C.: Training and Employment Notice 24-21, Department of Labor, May 5, 2022). ↩︎

- Congressional Research Service, Funding the State Administration of Unemployment Compensation (UC) Benefit (Washington, D.C.: June 2, 2023). ↩︎

- Andrew Stettner, Increasing the Taxable Wage Base Unlocks the Door to Lasting Unemployment Insurance Reform(Washington, D.C.: The Century Foundation, July 14, 2021). ↩︎

- Alix Gould-Werth, Fool Me Once: Investing in Unemployment Insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19 (Washington, D.C.: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, April 20, 2020). ↩︎

- National Employment Law Project, Questions and Answers About FUTA Taxes, (New York, New York: April, 2021).; Social Security Administration, Contribution And Benefit Base (Washington, D.C.: 2024). ↩︎

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Median Personal Income in the United States (St. Louis, Missouri: September, 2023). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Directors’ Guide.; Internal Revenue Service, FUTA Credit Reduction. ↩︎

- Will Raderman, “California has a $20 billion problem and no clear way to solve it,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 7, 2023. ↩︎

- Irena Asmundson and Mark Duggan, Overdue: Why California needs to reform unemployment insurance funding (Stanford, California: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, March, 2022). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, State Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Solvency Report (Washington, D.C.: February, 2020). ↩︎

- California Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2022-23 Budget: State Payments on the Federal Unemployment Insurance Loan (Sacramento, California: February 15, 2022). ↩︎

- Julie M. Whittaker, Unemployment Compensation (UC) and the Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF): Funding UC Benefits, (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, October 28, 2016). ↩︎

- 42 U.S. Code § 1101; Julie M. Whittaker, Unemployment Compensation (UC) and the Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF). ↩︎

- Stephen A. Woodbury and Margaret C. Simms, Strengthening Unemployment Insurance for the 21st Century: A Roundtable Report(Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Social Insurance, January, 2011). ↩︎

- Some states choose to supplement the federal allocations with additional funding. In 2019, 16 states directed $104 million in state administrative tax funds and 11 states contributed $98 million in general revenue to support UI administration, according to National Association of State Workforce Agencies data. This additional support is useful, but federal-level financing reforms are paramount given that the federal government is primarily responsible for funding program administration. See: National Association of State Workforce Agencies, FY 2019 State Supplemental Survey Report (Washington, D.C.: September, 2022). ↩︎

- Brent Parton, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines” (Washington, D.C.: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 18-22, Department of Labor, September 21, 2022). ↩︎

- Congressional Research Service, Funding the State Administration of Unemployment Compensation (UC) Benefit. ↩︎

- Lenita Jacobs-Simmons, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines” (Washington, D.C.: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 25-21, Department of Labor, September 2, 2021). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, Building Resilience: A plan for transforming unemployment insurance(Washington, D.C.: April, 2024). ↩︎

- Jane Oates, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2012 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines” (Washington, D.C.: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 25-11, Department of Labor, July 13, 2011). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Directors’ Guide. ↩︎

- State Innovation: Re-employment Focus in the Unemployment Insurance Program, Before the U.S. House Ways & Means Human Resources Subcommittee, 114th Congress (2016) (Testimony by Michelle Beebe, Unemployment Insurance Director of the Utah Department of Workforce Services). ↩︎

- Angela Hanks, “Encouragement for States to Use the Integrity Data Hub (IDH) available through the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Integrity Center.” ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, FY 2007 State UI Allocations(Washington, D.C.: 2007). ↩︎

- Brent Parton, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines.” ↩︎

- Rules typically requiring states’ base totals to fall no more than 5 percent could not hold since the total base amount was reduced by over 5 percent. A 10 percent reduction floor was imposed instead. See: Rosemary Lahasky, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines” (Washington, D.C.: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 10-18, Department of Labor, August 6, 2018). ↩︎

- Lenita Jacobs-Simmons, “Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 State Workforce Agency Unemployment Insurance (UI) Resource Planning Targets and Guidelines. ↩︎

- Annie E. Casey Foundation, ADULT POPULATION BY AGE GROUP IN UNITED STATES (Baltimore, Mayland: 2024). ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Outlook, President’s Budget (Washington, D.C.: 2023). ↩︎

- Statement for the record on “Investigating Pandemic Fraud : Preventing History from Repeating Itself”, Before the U.S. House Ways & Means Oversight Subcommittee, 118th Congress (2023) (Statement by Matt Darling et al., Niskanen Center). ↩︎

- U.S. Treasury, ESAA Account Statement Reports (Washington, D.C.: January, 2024). ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, Increase Taxes That Finance the Federal Share of the Unemployment Insurance System (Washington, D.C.: November 13, 2013). ↩︎

- Michele Evermore, New Jersey’s Worker-centered Approach to Improving the Administration of Unemployment Insurance(New Brunswick, New Jersey: John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, September, 2023). ↩︎

- Andrew Stettner, Increasing the Taxable Wage Base Unlocks the Door to Lasting Unemployment Insurance Reform. ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, Increase Taxes That Finance the Federal Share of the Unemployment Insurance System (Washington, D.C.: November 13, 2013). ↩︎