Conventional wisdom holds that Medicare is virtually immune to rollbacks. This view is understandable — Medicare was implemented under President Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s and has stood firm ever since. The program is widely popular and provides invaluable health benefits to older Americans. Attempts to slash Medicare benefits are, therefore, seen as politically damaging. Nevertheless, the assumption of rollback immunity did not hold up when policymakers added new Medicare coverage in the Reagan era. That legislative failure serves as a lesson for future efforts to improve social insurance programs.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a new law that expanded Medicare coverage for medicines and some catastrophic care. The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act (MCCA), as it was known, represented the ”first and biggest” expansion of Medicare benefits since the program was established. The MCCA ensured that prescription drugs, including insulin, received Medicare coverage. Beneficiaries could utilize more home health care and skilled-nursing facility services, and the temporary stays in skilled-nursing facilities no longer required prior hospitalization.

These kinds of improvements — under the Reagan administration, no less — are noteworthy in light of recent failures to advance commonsense Medicare expansions. Consider the obstacles to expanding Medicare coverage to dental, hearing, and vision care or allowing the program to negotiate (some) drug prices. Neither update has gotten done. Although the MCCA did not comprehensively insure long-term care (which is still urgently needed), some higher-cost services for seniors received more coverage. The legislation established a solid, albeit modest, health coverage upgrade for many.

But by late 1989, the MCCA’s provisions were largely gone. Congress repealed most of the fledgling law due to backlash from older constituents, who were unhappy with the new costs they were made to shoulder. Before passage, surveys indicated those over age 65 (i.e., Medicare recipients) supported the bill by an 85-point margin. That support dropped to a three-point margin just over a year later.

What happened?

In hindsight, this collapse probably should have been expected. The MCCA’s coverage upgrades were solely financed by additional premiums on Medicare recipients, as President Reagan’s secretary of health and human services, Otis Bowen, had proposed. In other words, rather than raising the necessary funds from a broader population (such as those currently on Medicare and active workers set to receive Medicare coverage in the future), Congress decided to target the immediate Medicare population alone.

A slight increase in the fixed monthly premiums of people enrolled in Medicare Part B, which covers doctor and outpatient services, funded approximately one-third of the cost. The other two-thirds of funding came from a supplemental premium affecting a fraction of beneficiaries of Medicare Part A, which covers inpatient hospital care. The supplemental premium was functionally an income surtax, capped at $800 for individuals and $1,600 for couples (around $2,000 and $4,000 in today’s dollars).

This financing structure is where problems arose. Low- to middle-income enrollees did experience a net gain in benefits (the value of new services exceeded the size of new fees), but many paying the supplemental premium experienced a net loss. Discontent was pervasive. Medicare enrollees across the whole income spectrum were unhappy with the size of premiums levied on them to pay for an increase in benefits.

Furthermore, the increase in covered services was smaller than expected — those who thought long-term nursing-home care would be insured under the MCCA discovered it was not. Frustration with the law became very tangible for members of Congress and led to the MCCA’s demise.

Diffuse the cost more

It didn’t need to be this way. The short lifespan of the MCCA shows the value in dispersing the cost of program expansions over a broader population. For instance, the government could have financed the new benefits the same way Medicare is already funded: by accruing payments from present and future recipients.

All Medicare enrollees could have received an overall increase in benefits, with the gains being easier for them to identify. Perhaps the legislation could have even included coverage of long-term nursing-home care if Congress had drawn on a wider tax base, as was suggested at the time. Unfortunately, policymakers continue opting for questionable finance designs that jeopardize the durability of key bills.

The failure of recent long-term care measures, in particular, reinforces the need for an updated approach to funding expansions. Long-term care provisions that passed as part of the Affordable Care Act were abandoned due to unreliable financing. Program participation was voluntary, which narrowed down the contributor pool. People not expecting to need the program anytime soon were unlikely to enroll. Financing the benefits would have required higher premiums from the small group of people who did sign up, setting off a classic insurance “death spiral” in which declining sign-ups and rising individual costs fuel one another. This model was as unsustainable as the MCCA approach.

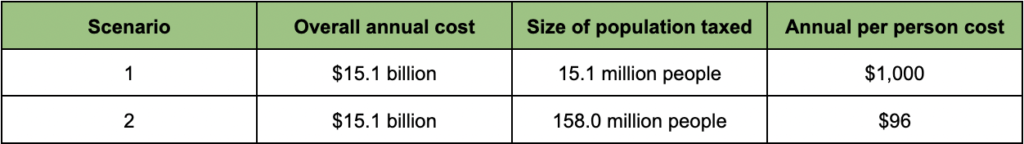

Program expansions can be made more resilient by locking in a wider revenue base. To demonstrate how noticeable benefit increases are possible without imposing an excessive cost burden on contributors, the financing of a Medicare “supplemental premium” is examined in two hypothetical scenarios using today’s dollars and population numbers. The revenue generated can be applied to a range of new coverage options. Here are the relevant statistics:

- The MCCA’s maximum supplemental premium would be about $2,000 per individual today.

- Approximately 40 percent of Medicare enrollees would be affected, according to the estimates made when the MCCA was passed.

- There are 37.7 million Medicare beneficiaries today.

- There are 158 million employees today.

Scenario One follows the original MCCA financing mechanism. 40 percent of Medicare recipients, 15.1 million people, pay the supplemental premium. The amount paid is $1,000 on average in this example, raising $15.1 billion for the MCCA Medicare expansion.

The same amount of money, $15.1 billion, is raised in Scenario Two. However, rather than solely burdening Medicare recipients with the financial liability, a tax is levied on all 158 million workers instead. The average worker would pay $96 annually in additional taxes to support the MCCA Medicare expansion (including Medicare recipients with jobs).

This breakdown can be seen below. The individual contributions (in 2022 dollars) required in the two scenarios are starkly different:

One-tenth as much is paid per person in Scenario Two relative to Scenario One. Individuals with labor income would only contribute $8 per month on average to help fund the new set of benefits (higher earners would cover more of the cost). Medicare recipients would experience greater and more apparent benefit gains in Scenario Two because they would not be the sole population paying the supplemental premium.

With the larger taxed population, policymakers could fund a much more significant expansion without coming close to the average per-person cost of Scenario One. Over $30 billion would be generated annually with an average “premium” of $200 on those with labor income, more than double what the MCCA-style premium generated. Less is needed from contributing individuals, and bigger benefits are more manageable when everyone chips in a bit.

The lessons learned

Bottom line: Beware of emulating the MCCA’s financial mechanism. Utilizing an inadequate tax base can hamper legislation. Better benefits are good, but policymakers cannot treat the funding avenue as a minor issue. Long-term viability is threatened when costs are concentrated among too few people and beneficiaries struggle to distinguish the net improvements. Expansions to a range of social insurance programs — family, disability, or old age benefits — are less financially burdensome on active recipients when more people, especially prospective beneficiaries, pay into the system. While just a fraction of Americans use these programs at a given moment, most will utilize them eventually. Spreading out the cost load of new coverage is critical. Policymakers cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the MCCA. Otherwise major legislative pushes risk being wasted.

Photo credit: iStock