Key takeaways:

- Replacing the U.S. tort-based compensation system for medical errors with a no-fault approach similar to that used in Nordic countries would likely benefit injured patients and health practitioners at little to no additional expense.

- A no-fault administrative system would compensate a larger number of injured patients more efficiently and at a lower cost.

- U.S. malpractice torts distribute compensation unevenly. Most patients injured due to medical error don’t receive compensation, while some win compensation when negligence did not occur.

- Malpractice torts are ineffective at deterring medical errors. The majority of medical errors do not meet a negligence standard.

- The process of assigning negligence undermines practitioners’ willingness to cooperate with the compensation process, limiting opportunities to learn from medical error.

- No-fault compensation systems are not difficult to implement in the U.S., and limited versions already exist in some states, such as Virginia and Florida. Given the potential for large and broadly shared gains, further reform and experimentation with no-fault compensation systems is warranted.

Introduction

The United States is one of the many countries that use adversarial torts to handle medical malpractice claims. In this system, patients injured due to a medical procedure can file a civil suit against the health provider they believe is responsible, along with their affiliated practice group. This system is widely criticized for its high cost and the limited compensation it provides to injured patients. Yet previous attempts at tort reform aimed at reducing medical malpractice litigation and damage awards have shown disappointing results, producing a political stalemate. A new approach to reform is urgently needed.

No-fault administrative compensation is an alternative to malpractice torts with a proven track record of success that is used in countries such as New Zealand, Sweden, and Denmark. This system is more efficient than litigation, allowing more patients to receive compensation per dollar spent. To illustrate, despite spending more per person on medical injury compensation claims and administration than Denmark, the United States compensates far fewer patients relative to the size of its population. Malpractice litigation has other apparent downsides: unduly burdening medical practitioners, likely encouraging wasteful care, fostering secrecy regarding medical conduct, and damaging patients’ trust in the broader medical system.

A couple of U.S. states have already adopted no-fault administrative compensation, albeit in a limited fashion. In Florida and Virginia, administrative compensation is used for claims of neurological birth-related injuries. Yet further experimentation in this direction is likely warranted. Accounting for the greater efficiency of no-fault administrative compensation and the other wasteful spending induced by the threat of liability, it is possible that adopting a no-fault scheme could better compensate for injuries while simultaneously reducing overall costs—all while ensuring patient safety.

A brief overview of patient compensation systems

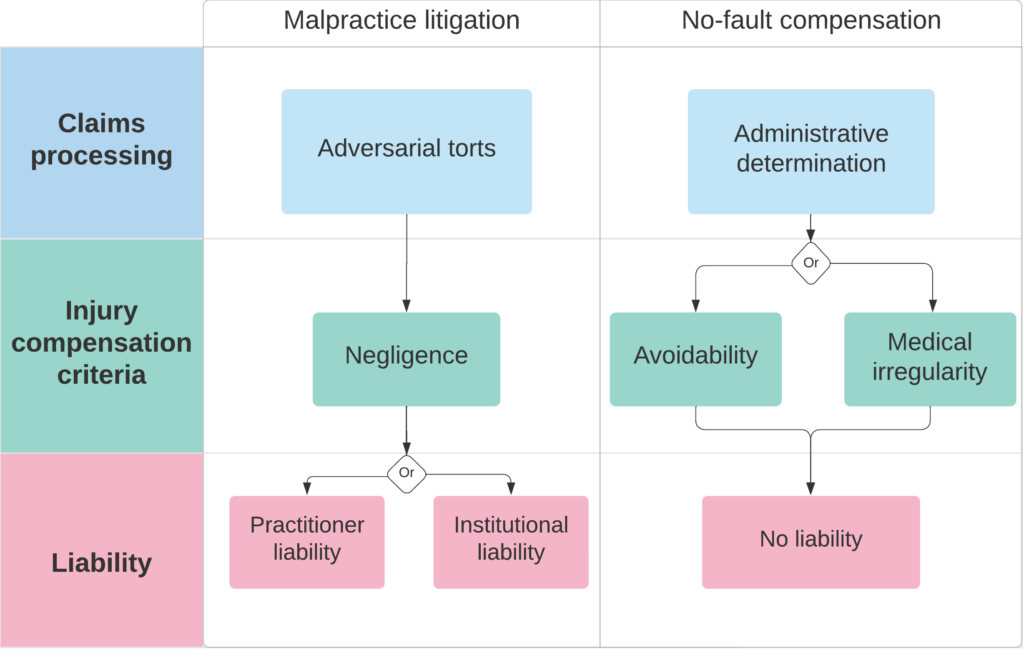

Patient compensation schemes vary from country to country but broadly fall under one of two types: adversarial malpractice torts and “no-fault” administrative systems.

It’s useful to compare these two approaches to medical injury compensation on three dimensions:

– How injury compensation claims are processed.

– The criteria used to evaluate them.

– The extent to which practitioners are deemed individually liable for successful claims.

How injuries Are compensated: malpractice litigation vs. no-fault compensation

Adversarial malpractice torts

For an adversarial malpractice tort claim to succeed, a court or jury must find “negligence” on the medical provider’s part. In the United States, courts have defined negligence as deviations from the expected standard of skill and care. To establish that standard, courts seek to understand what similarly situated health professionals would have done, relying heavily on expert testimony in addition to medical texts and clinical practice guidelines. Proving that a provider’s actions constitute negligence — and that this negligence is more likely than not causally linked to a plaintiff’s injury — is a highly complex and often contentious process. This process can drag on for years, especially if the parties don’t agree to settle the suit outside of court. Non-dismissed claims that don’t make it to trial — meaning either that the parties settled or that the suit was withdrawn before a courtroom verdict — take, on average, over two years to resolve. The roughly five percent of claims that are resolved at trial take over three years to close. If a plaintiff can convince the court that their injury resulted from provider negligence, the jury orders the defendant to pay compensation. This compensation is typically calculated based on economic damages (e.g., time spent not working due to the injury) and non-economic damages (e.g., physical or emotional pain), subject to any caps that state governments may have instituted.

In the United States, practitioners and/or institutions are named as defendants in malpractice suits, and claims can be astronomical, sometimes in the multiple millions. U.S. practitioners overwhelmingly rely on malpractice insurance to manage this otherwise catastrophic financial risk. Premiums for malpractice coverage are based on several factors, including age, specialty, years of practice, and participation in malpractice risk-management training. The organization of financial risk under malpractice torts differs somewhat from country to county, with some using alternatives to liability insurers. For instance, in Canada, doctors are represented by the Canadian Medical Protective Association, primarily funded by Canadian taxpayers with supplementation by fees from doctors. In the United Kingdom, liability for many medical services has been shifted onto the country’s publicly-funded National Health Service rather than individual practitioners.

Practitioners generally aren’t directly on the hook for malpractice damages, with only a tiny minority of vulnerable practitioners failing to take out liability insurance. As such, the enormous hassle of the legal process and the associated work disruptions are often the most salient consequence for practitioners. To illustrate, estimates suggest the average U.S. physician spends around 11 percent of their career with an open malpractice claim against them. Also important are reputational and professional difficulties created by paying out a malpractice claim. In the case of U.S. practitioners, settling or losing a malpractice lawsuit results in them being listed on the federal National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), which can complicate future job opportunities.

No-fault patient compensation

An increasing number of countries, including New Zealand, Sweden, and Denmark, have ditched adversarial torts in favor of “no-fault” compensation for injured patients. Some U.S. states have also established limited no-fault compensation schemes, including Florida and Virginia’s no-fault systems for neurological birth-related injuries.

The three key features of no-fault compensation systems are:

1. Compensation eligibility is determined through administrative processes rather than adversarial torts.

2. Compensation does not depend upon whether a patient’s injury resulted from demonstrable “negligence” on the part of a health provider.

3. Determination of patient compensation is separated from any potential disciplinary measures health providers face.

Such systems bypass the inefficient, time-consuming process of adversarial torts while facilitating a more harmonious relationship between health providers and injured patients.

In Nordic countries, compensation is determined based upon “avoidability” rather than negligence. Under an avoidability standard, injured patients must only show that the injury should have been avoidable had the care been delivered at the highest standard of care and expertise. A third-party evaluator determines compensation based upon medical records, precedent, and experts’ opinions. A distinctive feature of Nordic systems is the “firewall” between compensation claims and disciplinary actions against health care providers, a divide that encourages provider cooperation. While patients are free to file a separate complaint against their provider in pursuit of disciplinary action, doing so has no bearing on the compensation process itself. This model initially emerged in Sweden as a voluntary alternative to torts in 1975 and was made mandatory for all health providers in 1997. The success of Sweden’s no-fault system has resulted in variations of its example spreading to Finland, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland.

New Zealand’s no-fault system is slightly different. In New Zealand, compensation is determined based upon what is best described as a “medical irregularity” standard. “Irregularity” differs slightly from “avoidability” in that compensation is based solely on whether the injury represents a deviation from the anticipated outcome, regardless of whether any departure from clinical best practices can be identified. The “medical irregularity” standard also best describes Florida and Virginia’s birth-related neurological injury compensation system, which provides compensation administratively for a predefined set of medical injuries.

While New Zealand separates compensation determinations and disciplinary investigations into two separate processes, there is no Nordic-style “firewall” between the two tracks concerning information-sharing. Still, reports from the compensation track must be made to the licensing or health safety authorities responsible for discipline only if there is a “risk of harm to the public,” a condition that, in practice, is not met by most compensation claims.

Hybrid compensation systems

Finally, some countries, including France and Belgium, utilize hybrid systems, combining tort malpractice and no-fault compensation aspects. These systems retain the notion of blame while expanding compensation to a wider pool of patients. Since 2002, French patients with serious medical injuries have had the option of pursuing compensation through malpractice litigation or through commissions that follow roughly the same steps as Nordic ones. If a physician is found to have committed a negligent error in a case pursued through the commission process, liability insurers will pay the compensation. But if there is no evidence of negligence, the state will pay. Hybrid schemes, however, are tricky to implement in practice though. As Maryland’s experience with the Health Care Alternative Dispute Resolution Office shows, mandating alternative dispute resolution with courts as a fallback option can result in needless administrative steps before parties inevitably push the actual determination to the courtroom.

Administrative determination is more efficient than torts

Seeking redress for injury through the legal system is less efficient than using administrative processes. Estimates suggest the average U.S. physician spends around 11 percent of their career with an open malpractice claim against them. Despite the volume of claims, many Americans struggle to receive compensation following a medical injury.

In the U.S., injured patients must engage in an adversarial legal struggle against their health care provider to demonstrate a causal link between an injury and an instance of “negligence.” Navigating this without the help of a lawyer is virtually impossible. Health practitioners are heavily incentivized to deny any malpractice claims against them, regardless of merit. In addition to any financial liability that they would personally be on the hook for, a successful malpractice claim results in being listed in the National Practitioner Data Bank, potentially complicating employment prospects. And even if a health practitioner might like to admit wrongdoing, their liability insurer generally requires them to deny any claims and hand over management of the legal defense. Even what ought to be the most straightforward claim almost inevitably devolves into a costly years-long slog. Medical malpractice plaintiffs in the U.S. have to wait for five years on average for an initial court decision.

By comparison, seeking injury compensation under a no-fault system is simple. It is typically done by patients alone or with the assistance of a doctor. In Denmark, many doctors voluntarily file claims on behalf of their injured patients. This process is streamlined since administrators don’t need to identify “negligence” on the health care provider’s part. Providers have nothing to lose from cooperating with claims administrators. As a consequence, the Swedish no-fault system rules on 70 percent of claims within eight months of filing. Even more impressively, the average medical injury claim in New Zealand takes only 16 days before a decision is communicated to the patient. The societal benefits of speedier, less adversarial compensation are likely broader than mere convenience, with massively improved return-to-work rates observed among New Zealanders. They received compensation through the country’s no-fault medical compensation system compared to those seeking compensation for the same injury going through the country’s adversarial worker-compensation system.

The drawn-out legal battles that result from tort-based malpractice compensation are incredibly costly. Apart from payments made to lawyers, the collection of medical records, expert review of the case, court filing fees, and trial-related expenses can easily total in the tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. In the U.S., total legal costs in the medical liability system are estimated to be roughly $10 billion annually. Approximately 57 percent of this spending goes to administration and overhead rather than patients. For comparison, New Zealand’s treatment injury compensatory body spent only five percent of its budget on administrative costs in 2020. In Denmark, this proportion was 18 percent.

Efficiency and scope of compensable Injuries

Though malpractice torts are less administratively efficient on a per-claim basis than no-fault systems, whether these systems are more costly depends upon the scope of compensated injuries and the per-injury generosity of that compensation. In purchasing power adjusted terms, U.S. malpractice expenses, including payments and related administration, amount to around $30 per capita annually. In contrast, Denmark spent only $19 per capita in the same year despite paying out more widely. The even larger scope of injuries eligible for compensation in New Zealand makes their system relatively more expensive. In New Zealand, the no-fault system for treatment of injuries cost around $55 per capita in 2019, again at purchasing power parity.

The negligence standard unevenly compensates patients

Under the U.S. tort-based malpractice system, the costliness of court battles means that lawyers are highly unlikely to take up patients’ claims with alleged damages under $100,000, given that their own compensation is usually contingent on success in court or settlement negotiations. And, often, claimed damages must be much higher than that to entice a lawyer’s aid. As a result, injured patients without massive damages have little-to-no chance of accessing a malpractice lawyer, shutting many legitimate potential claimants out of compensation. To illustrate, the average malpractice payment was $348,000 in 2018, according to the National Practitioner Data Bank.

No-fault systems present fewer barriers for potential claimants, particularly for those with smaller claims. The minimum damage amount to file is less than $1,700 in Denmark. The average payout is only $30,000, as it reflects medical mishaps both large and small. A per capita comparison illustrates how many American patients are going empty-handed. In 2019, Sweden, with its low threshold for a claim, compensated around 7,700 patients that year, or 75 compensations per 100,000 inhabitants. Similarly, Denmark had 48 successful claims per 100,000 inhabitants. Compensation in Nordic countries is dwarfed by New Zealand’s rate of 209 per 100,000 inhabitants, owing to the country’s expansive definition of compensable injuries. In the United States, the compensation rate, including both settlements and jury verdicts, is realistically somewhere between four and seven per 100,000 inhabitants after adjusting NPDB figures for claims made against nonpractitioners.

Legal deterrence is ineffective at improving patient safety

The third major component of injury compensation systems is who bears responsibility for medical errors. A central justification for malpractice torts is that they deter medical errors by assigning blame.

Even for the small fraction of medical errors that are sensitive to deterrence, the effectiveness of malpractice torts is highly dubious. Indeed, the bulk of studies suggest that greater malpractice liability doesn’t improve patient health outcomes. Perhaps the most informative study on this topic took advantage of selective immunity from malpractice suits on military bases. The study found that immunity from malpractice reduced spending on medical treatments by five percent without measurably impacting patients’ health outcomes.

Tort claims are a highly flawed proxy for harmful medical error. Just a small fraction of estimated medical errors result in a malpractice claim, both because negligence is inherently difficult to determine and because practitioners have an incentive to frame such errors as an unavoidable outcome of the procedure. Recent estimates put the number of U.S. patients injured due to medical error between 200,000 and 500,000 annually. Just 11,590 medical malpractice payments were reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank in 2019. However, this database omits defendants that are hospitals and clinics. Based on more inclusive claims data available in some states, the total number of successful claims is higher, likely between 16,000 and 23,000 in 2018 — still, a small fraction of estimated medical errors. Multiple sources put the overall success rate for malpractice claims at around 25 percent, meaning the total number of claims was likely between 60,000 and 90,000. This range, however, includes lawsuits that are not seriously pursued. Careful review using a sample that omits these frivolous or unseriously pursued claims suggests substantial numbers of false negatives and false positives. Roughly a quarter of successful claims lacked an identifiable medical error, and researchers identified medical errors in a similar share of unsuccessful claims. Tort litigation’s weak correspondence to medical error and the unpredictability of associated legal outcomes suggest it is a highly flawed tool for achieving its theoretical aim to compensate injured patients while deterring medical error.

Some experts believe locating responsibility for medical errors at the level of individual practitioners misunderstands the problem. In its 1999 landmark report, To Err is Human, The Institute of Medicine concluded that medical errors are more likely to stem from system failure or unavoidable human error than insufficient incentives for practitioners to prevent such errors. Individual practitioners face more than adequate encouragement – reputational, ethical, and financial – to pursue patients’ health interests. In this sense, locating responsibility with individual practitioners is only effective at deterring a small fraction of medical errors. In such cases, most medical errors wouldn’t produce the massive damages necessary to motivate a lawsuit in the first place.

No-fault systems arguably reflect a better understanding of how such errors occur. They support patient safety by fostering open communication environments where practitioners identify and learn from mistakes. Furthermore, the system’s comprehensive reporting allows researchers to better understand how medical errors arise, potentially driving further improvements in patient safety. At the very least, practitioners in no-fault are made aware of instances when a departure from the highest standard of care was associated with patient injury, even if they are not punished for it. This simple recognition often doesn’t even occur in the United States. Legal remedies are usually pursued only for the largest claims. When patients do go to court, a well-prepared apparatus of damage-control dissuades practitioners and institutions from being open about what happened.

Malpractice torts encourage wasteful medicine

Practitioners do respond to the malpractice environment, just not in a manner that benefits patients. Policies impacting the likelihood and size of a malpractice claim influence medical practice patterns, particularly when it comes to diagnostic tests. Indeed, the cost of so-called “defensive medicine” — attempts to minimize the odds of litigation through excessive medical treatment — has been estimated at $46 billion annually.

A no-fault system should reduce defensive medicine, but the overall impact on health care costs is unclear. Savings from any avoided defensive medicine might be offset by the fact that practitioners freed from the burden of litigation would have time to see more patients (generally a good thing given our physician shortage, but not a cost-cutter). Furthermore, evidence suggests that practitioners in certain circumstances avoid providing medical services to certain patients posing a high risk of litigation, a practice sometimes termed “negative defensive medicine.” Direct evidence on the relation between no-fault compensation and health care costs is limited. Still, countries’ adoption of no-fault compensation is at least associated with slower growth in health care spending after controlling for other relevant factors. Even if overall reductions in health care costs fail to materialize, patients receiving more worthwhile treatments would be a good thing.

That the abstract threat of litigation itself is the primary driver of defensive medicine, rather than the prevalence of paid claims, is consistent with the findings from efforts at tort reform in the United States, which often fail to find evidence of reduced health care spending as a result of policies such as caps on medical damages. Given the widespread use of liability insurance among U.S. practitioners as well as the weak underlying connection between malpractice and medical errors, we shouldn’t be surprised that wasteful defensive medicine isn’t especially sensitive to incremental liability reforms.

Legal deterrence distorts medicine in other ways, too

Fear of malpractice liability adversely impacts the internal culture of medicine as well. Torts deter transparency, as opacity is a way to effectively manage litigation risk. As the Institute of Medicine has observed:

The potential for litigation may sometimes significantly influence the behavior of physicians and other health care providers. Often the interests of the various participants in furnishing an episode of care are not aligned and may be antagonistic to each other. In this environment, physicians and other providers can be cautious about providing information that may be subsequently used against them.

Malpractice litigation has blind spots beyond its failure to grapple with straightforward system error. The malpractice system is incapable of discouraging statistically harmful practices in which causation can’t be determined in the case of a specific patient. For instance, unnecessary diagnostic tests are routinely identified as one of the most common forms of defensive medicine. Their overuse introduces additional risk for patients, possibly even a heightened risk of developing cancer due to radiation overexposure. In these circumstances, the logic of the courtroom is outright incompatible with evidence-based medicine.

The adversarial nature of malpractice litigation conflicts with the goal of evidence-based medicine in other ways. The promotion of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has a fraught history in the United States, owing to the aggressive use of malpractice torts. In 2018, the Trump administration zeroed out appropriations for the National Guidelines Clearinghouse, prompting the resource to go offline entirely, despite previously drawing 200,000 monthly visitors, on average. As Stat News reported at the time, a key reason some providers opposed the clinical practice guidelines was that their widespread adoption “exposes them to liability if they happen to deviate from doctrine.” As of this writing, these guidelines remain offline.

Under adversarial malpractice torts, injured patients generally receive an icy response from their providers. To mitigate risk, hospitals and providers are discouraged from acknowledging it, much less offering a genuine apology. While a majority of states have laws protecting statements expressing sympathy, these protections do not extend to statements such as “I’m sorry I hurt you,” or, “I’m sorry I made a mistake when I administered the wrong medication.” Yet even such legal protections would miss the point — apologies undermine a practitioner’s ability to frame an injury as an unavoidable risk of the procedure, even when they know better. Ensuring that apologies don’t amount to an admission of fault from a legal perspective doesn’t alter the fact that an apology itself communicates to patients that they are entitled to seek compensation. While difficult to quantify, the cold reception received by injured patients clearly results in emotional harm and potentially even damages trust in the broader medical system.

Time to end lawyer sovereignty over medicine

Almost everyone would likely be better off if we cut lawyers and courts out of the injury compensation process. Malpractice litigation is highly inefficient, unfair to injured patients, and likely harmful to American medicine. By relying on malpractice torts to compensate patients, we’re not just lighting money on fire, but burning our hands in the process. At the same time, so-called “tort reforms” that tinker along the edges of malpractice, such as caps on liabilities, fail to address the current system’s shortcomings. A more fundamental overhaul is needed, and no-fault administrative compensation is an attractive alternative.

At the state and/or federal level, we should be experimenting with policies that more closely align compensation with medical injury. We need not radically overhaul the system overnight, either. As countries like France and U.S. states such as Virginia demonstrate, compensation schemes can be rolled out in a targeted fashion for groupings of medical injuries. And as Virginia’s case further illustrates, no problems are created by the greater degree of privatization in the U.S. health care system. Standardized contributions from health care practitioners would replace current professional liability premiums. This could be done either by converting existing liability insurers into fee collectors for the general compensation fund, as was done in Sweden, or by moving fee collection to the medical licensing body, as was done in New Zealand. The primary obstacle is political, given that lawyers are an incredibly powerful interest group in the United States. Other interests, such as the malpractice insurance industry, would likely prefer to see the current system maintained as well.

Of the international compensation standards to borrow from, the “avoidability” standard used in Nordic countries might be the easiest to implement in the United States. The upshot here is that it would be feasible for total direct costs (excluding potential savings at the broader health system level) to come in at or below the current malpractice system. Past analyses concur that a patient compensation system modeled on the lines of Sweden’s would likely be affordable in the United States. Using too comprehensive or narrow a definition of a compensable injury would undermine the prospects of a “win-win” reform that benefits both health practitioners and injured patients.

The benefits of compensating injured patients through tort litigation are hazy at best, but the harmful drawbacks are clear. Malpractice torts are extremely inefficient, expending enormous resources to come to a conclusion regarding “negligence” whose relevance to patient safety is tenuous at best. In essence, this means patients are being denied injury compensation to prop up what amounts to an arbitrary legal exercise. While the looming shadow of litigation doesn’t seem to improve patient safety, it is influencing the relationship between practitioners and their patients in harmful ways. The case for replacing malpractice torts with no-fault administrative compensation is strong.

Photo Credit: iStock