Whether or not one is a fan of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All plan (MFA), he is right about one thing: America needs a health care system more like those of other wealthy countries. Yet if “Medicare for all” is how we should get there, please stop calling it “single payer.” The single-payer label distracts attention from the main goal of health care reform, energizes the opposition, and is not an accurate description of the Sanders’ plan.

The goal is universal access

Single-payer is not the goal of health care reform. The goal is universal access to health care; not “access” in the sense of simply having the opportunity to buy into the system if you can afford it. True universal access would mean a system in which anyone who needs health care can go to the doctor’s office, the hospital, or the pharmacy and get what they need with the certainty that they can afford it, no matter how modest their means.

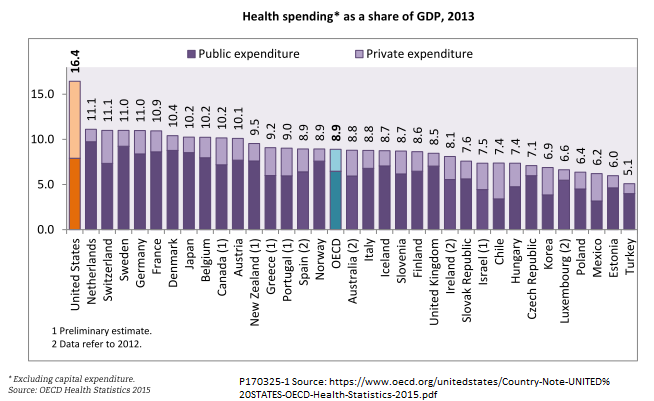

Single-payer is better understood as simply one way of getting to the goal of universal access. Under a true single-payer system, when you went to get care of any kind, you would just show your health care ID card and the government would directly reimburse the provider in full. That would be nice. The problem is, no such system exists anywhere in the world – not even in the universal access systems we admire most: Sweden, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, or whichever is your favorite. In all of those countries, the government pays some of the health care bills and private sources pay some. As the chart below shows, the government contribution is greater than it is in the United States almost everywhere, but it is not 100 percent anywhere.

How do other countries make universal access work? There are so many models they are hard to describe in brief, but one way to classify them divides health care systems into three main types:

- In the Bismarck model, named for the German Empire’s first chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, hospitals and doctors are private. Payments are made through private, closely regulated, not-for-profit insurance funds. Prices are tightly controlled. The funds are financed by a mixture of taxation and individual contributions. Germany, Japan, France, and Switzerland, among others, follow variants of the Bismarck model.

- In the Beveridge model, named after the founder of Britain’s National Health Service, William Beveridge, many (but not all) doctors are government employees and many (but not all) hospitals and clinics are publicly owned. The government pays for services from tax revenues. This system, used with variations in the UK, Scandinavia, Spain, and New Zealand, is what most Americans think of when they say “single payer” or “socialized medicine,” but even in these countries, there is some decentralization and a smaller, parallel, system of private, for-pay health care.

- In the National Health Insurance model, providers are private but fees are paid by a national insurance fund. Providers are subject to cost controls. Canada and Korea use this system. Canada’s is decentralized by province.

Few, if any, of these systems provide coverage as broad as that envisioned by Sanders’ MFA. For example, Canada has limited coverage of prescription drugs (although the government does control prices), and many countries do not fully cover long-term care, mental health care, eye care, or dental care. Some of the countries listed have co-pays or deductibles for some services.

In addition, there are other proposals for universal health care access that do not fit easily into the above classifications. Universal catastrophic coverage, an idea beloved by economists for its theoretical simplicity, is one of them. Another example is Singapore’s unique system, which features mandatory private insurance with subsidies for the poor.

In short, there are many routes to the goal of universal health care access. Americans, in their wisdom, may decide to adopt something like the Sanders plan, but if they were to get the same result in a different way, there would be no great reason to be disappointed.

Even Sanders’ Medicare for All is not a true single-payer system

Another reason to drop the single-payer term is that it is not even an accurate description of Sanders’ MFA proposal itself. MFA, in which providers would remain mostly private, is closer to the national insurance model than it is to the Beveridge model, where providers are more often government employees and institutions.

Sanders’ plan also allows for parallel, private health care outside the framework of MFA. Sec. 303 of the draft bill, “Use of Private Contracts,” gives providers the choice of working within MFA or opting out and entering into private contracts with patients. The only real restrictions on private contracts are that they must be all or nothing. A provider cannot accept the standard reimbursement for a treatment from MFA and then collect an additional fee from the patient for the same treatment.

There are several reasons that some patients and providers might prefer private contracts. For example:

- MFA guarantees coverage only of services deemed “medically necessary” (Sec. 202). Presumably, some kinds of alternative medicine, some experimental treatments with unproved effectiveness, and some purely cosmetic procedures would be deemed not medically necessary, but providers could still offer them through private contracts.

- Some providers might develop exceptional reputations (deserved or undeserved) for the quality or effectiveness of their treatments. If so, they could very likely attract enough wealthy patients to earn more outside MFA than within it.

- In some cases, MFA patients might encounter waiting periods. Private contracts would offer a way for those willing to pay extra to get desired treatment sooner.

Just how widespread the use of private contracts might be would depend on how generously or tight-fistedly MFA as a whole is administered. If medical necessity is interpreted broadly, reimbursement rates are generous, and funding sufficient to ensure timely access to care, then for-contract health care would probably be a small niche market, as it is in the UK. If aggressive cost controls excluded too many treatments, made participation unattractive to providers, and led to long waiting periods, Sec. 303 might give rise to a substantial parallel health care system, with MFA itself used mainly by low-income households.

The single-payer label is a political distraction

A third reason to drop the single-payer label is that it is a political distraction. A recent Pew survey shows that 57 percent of Americans, including 30 percent of Republicans, believe it is the government’s responsibility to make sure that everyone has access to health care. However, fewer than half of Democrats (43 percent) and very few Republicans (10 percent) favor a single, national system. Most say they would prefer a mix of government and private programs.

Calling Sanders’ plan “single-payer,” then, makes it an unnecessarily hard sell. With its predominantly private providers and its allowance for a parallel private payment system, MFA is, in truth, a mixed system. If the Pew numbers are accurate, swapping the “single-payer” label for “universal access” would more than double its support among both Democrats and Republicans.

Backers of Sanders’ plan should seize on the fact that Republicans are already on record as favoring universal health care access. Their 2017 House Policy Brief on repeal and replace specifically endorses “a patient-centered health care system that gives Americans access to quality, affordable care” and promises “coverage protections and peace of mind for all Americans – regardless of age, income, medical conditions, or circumstances.” True, judging by their votes on recent bills that would have reduced health care coverage, rather than expand it, many Congressional conservatives don’t take this language seriously. Still, as long as it remains the official party line, Democrats can point out that MFA only fulfills a universal access pledge that the GOP itself has made.

The bottom line

The introduction of Sanders’ Medicare for All has triggered a debate within the Democratic party. Many of the most likely 2020 presidential candidates have endorsed the bill. They don’t want to be outflanked on the left, so why be satisfied with a health care proposal that merely matches the performance of Germany, France, or the UK? Why not leapfrog our European peers and introduce a system that offers broader coverage, less cost-sharing, and more centralization than any of them?

At the same time, even some dedicated progressives have doubts. “Is this really where progressives want to spend their political capital?” economist Paul Krugman asks in his New York Times column. Writing for Axios, Drew Altman, a strong supporter of universal access, worries that “single payer” offers Republicans too easy of a way to change the subject. More narrowly tailored policy ideas could still be popular on the left and in the center, he says, while offering far smaller targets for opponents than a sweeping single-payer plan would.

It is too early to tell how this debate within the progressive camp will turn out. But whether you fully support Sanders’ bill or favor something less politically ambitious, don’t call it single payer. Call it universal access. That’s what it is, that’s what a majority of the electorate wants, and that’s the way to sell it.