The notion that immigrants come to the United States to access public programs has become something of a popular myth. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), better known as welfare reform, introduced a five year ban on lawful immigrants using public benefits with very few exceptions, like refugees and asylees. This helps ensure new immigrants are net fiscal contributors to the U.S. Treasury — a fact which empirical studies consistently confirm. Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for public benefits.

Yet some myths are harder to correct than others. Indeed, members of the current White House appear to hold the same misconceptions, as revealed most recently in a draft executive order from January 2017 which claims “households headed by aliens are much more likely than those headed by citizens to use Federal means-tested public benefits.” No citation is provided.

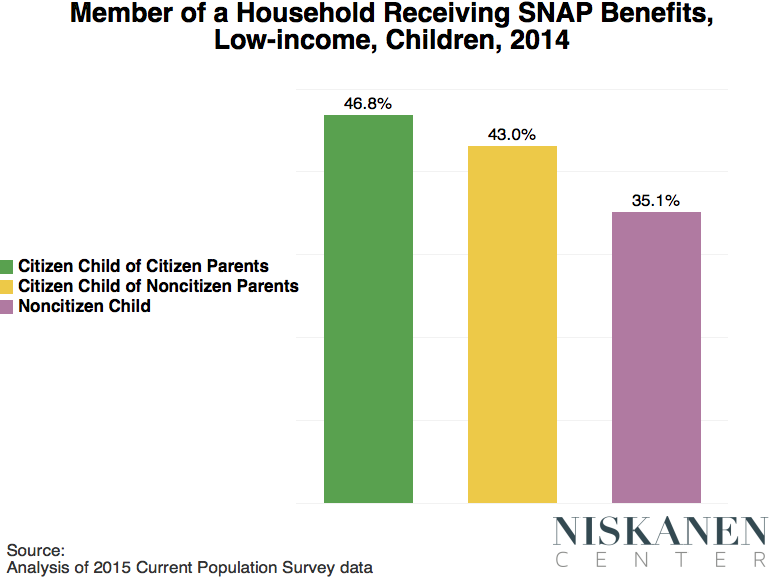

In a new report, my colleague Robert Orr and I demonstrate that low-income immigrants are less likely to access to public benefits than their native-born counterparts. This is even true when they are otherwise fully eligible. For example, under current rules for SNAP, noncitizens can bypass the five year ban if they have children under the age of 18, are blind or disabled, have a military connection, or have worked for 40 qualifying quarters. Nevertheless, only 35.1% of low-income noncitizen children are members of a low-income household receiving SNAP, compared to 46.8% for the native-born. Citizen children of noncitizen parents also tend to participate in SNAP at a lower rate.

This report follows-up on the report we released Friday on the redefinition of “public charge,” which can be found here.