The European Council and the European Parliament reached a provisional agreement on the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) in December 2022. The EU CBAM would levy a tariff on imported goods across specific sectors, mirroring what domestic goods are subject to under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). The policy aims to protect EU manufacturers’ competitiveness against foreign manufacturers and encourage EU’s trading partners to decarbonize.

Here’s a quick recap of the legislative timeline of the proposal:

- On July 14, 2021, the European Commission officially introduced the EU CBAM proposal.

- On December 21, 2021, European Parliament’s lead rapporteur, Mohammed Chahim, published suggested amendments to the proposal calling for a more ambitious CBAM.

- On March 15, 2022, the Council reached its position on the proposal.

- On June 22, 2022, the European Parliament voted its position.

- From July 11 to December 13, 2022, trilogue negotiations among the Parliament, the Council, and the Commission took place.

- On December 13, 2022, the Council and the Parliament reached a provisional agreement.

According to the Council’s press release, the agreement needs to be confirmed and adopted by the EU member states and the European Parliament to be finalized.

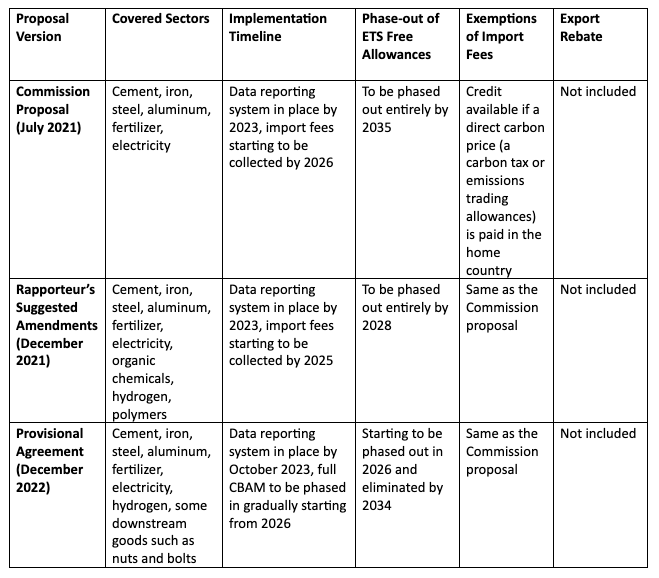

EU CBAM Proposal Versions

Source:

1) “The EU unveiled a carbon tariff. How should the U.S. respond?” Shuting Pomerleau

2) “European Parliament’s Lead Rapporteur Recommends a More Ambitious CBAM,” Shuting Pomerleau

3) European Council Press Release

The latest CBAM proposal is similar to the initial version, adding hydrogen and some downstream goods to the covered products. It is looking to put in place a reporting system by October this year to gather emissions data associated with the covered imported goods and start collecting import fees in 2026. The ETS free allowances assigned to carbon-intensive sectors will start to be phased out in 2026 and eliminated entirely by 2034. As the CBAM is replacing the free allowances to protect EU producers’ competitiveness, the CBAM will be phased in at the same speed as the free allowances will be phased out.

It’s important to keep in mind two points with the EU CBAM proposal:

First, despite its name, this is not a standard border adjustment. A border adjustment includes an import tax and an export rebate that go with a domestic tax. It would level the playing field between domestic and foreign producers. None of the different versions of the EU CBAM proposals includes export rebates. Therefore, the proposal is essentially an import tariff. Not giving rebates to the EU exporters might encourage them to relocate their production facilities to jurisdictions with more lax climate regulations to avoid paying for the ETS emissions allowances.

Second, it is unclear whether this proposal will be compliant with the WTO rules. EU lawmakers would have to ensure the import fees levied on foreign producers are no greater than what domestic producers are subject to. Additionally, it may be challenging to allow foreign producers to claim credits against the import fees based on their home countries’ climate policies. This differential treatment of trading partners might violate WTO’s non-discrimination rules. Administratively, it could be onerous to allow foreign producers to claim partial or full credits on different products.

It is expected that the EU will move forward with the CBAM proposal and make it law. It remains to be seen what the details will be in the final agreement. While the policy aims to incentivize trading partners to decarbonize, enacting carbon tariffs as in the current proposal scope might have unintended consequences. The EU lawmakers must continue to have discussions to improve the policy.