Although headline inflation continues to fall and unemployment is near a 50-year low, the Federal Reserve still faces some tricky policy decisions over the next few months. Many of these have to do with the unusual volatility of relative prices during the 2021-2022 inflation, a topic that I wrote about in a recent commentary. This piece picks up where that one left off. It focuses on the behavior of the subset of prices that constitute the so-called supercore relative to prices that are more flexible.

Supercore prices have been in the news lately because some observers think the Fed is targeting them. This commentary will argue a focus on supercore inflation may have led to a more-than-prudent degree of monetary policy tightening by late 2022 and early 2023. The fact that high interest rates appear to have been a contributing factor to the banking crisis that was touched off by the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March only strengthens the case.

So, what is the supercore?

So, what, exactly, is the supercore? The notion of ordinary core prices is familiar enough. The core consumer price index, for example, is the ordinary CPI with the highly volatile prices of food and energy removed. The personal consumption expenditures index, a CPI alternative, also has a core version that removes the same two sectors. Measures of the supercore go further by removing still more items.

The impression that the Fed is targeting supercore inflation was reinforced by a press conference held on February 1 by Chairman Jerome Powell. In answering a reporter’s question, Powell divided prices into three sectors. “In the goods sector,” he said, “you see inflation now coming down because supply chains have been fixed … In the housing services sector, we expect inflation to continue moving up for a while but then to come down … So, in those two sectors, you’ve got a good story. The issue is that we have a large sector called nonhousing service — core nonhousing services, where we don’t see disinflation yet.” Although he does not use the term, what Powell calls core nonhousing services is what others call the supercore.

It is almost as if Powell is treating the problem of inflation the way a frontline surgeon might treat a wounded soldier. “We’ve stopped the bleeding in his leg; we’ve got the bullet out of his shoulder; now all we’ve got to do is get that pesky piece of shrapnel out of his neck.” But is continuing to tighten monetary policy until supercore prices, too, stop rising really a good idea? Read on.

Why supercore prices are sticky

Economics 101 teaches us that market prices rise or fall in response to changes in supply and demand. True enough, but some prices respond faster than others. At the flexible end of the spectrum, the prices of oil or wheat quoted on commodity exchanges change by the minute. At the sticky end of the spectrum, prices like city bus fares or college tuitions are likely to change just once a year, if that often.

Economists suggest a variety of reasons for price stickiness. Some point to the costs of announcing and implementing price changes, such as a restaurant’s cost of printing new menus or a laundromat’s cost of adjusting the coin mechanisms on its washers and dryers. Others emphasize strategic considerations, such as the fear that the first seller to raise prices might lose market share to competitors who are slower to change. Marketing considerations like the fear of annoying loyal customers may be another factor. And prices that are subject to long-term contracts often can change only when those contracts expire.

The Atlanta Fed publishes monthly indexes for a flexible CPI and a sticky CPI. Using an admittedly arbitrary cutoff, it classifies flexible prices as those that change, on average, at least once every 4.3 months and sticky prices as those that change less frequently. That division makes about half the prices in the CPI flexible and half sticky. If weighted by value, the split is about 30 percent flexible and 70 percent sticky.

The bulk of the sticky CPI consists of services. The Atlanta Fed derives a “core sticky CPI” by removing its only food or energy element, “food away from home.” It then derives a measure called “core sticky CPI ex shelter” by further removing the category “owner equivalent rent.” That index, more than 90 percent of which is made up of services, covers 45 percent of the full CPI.

In what follows, I will use the Atlanta Fed’s core sticky CPI ex shelter as a measure of the supercore. It is probably not the exact measure of “core nonhousing services” to which Powell referred at his press conference, but if not, it is very close.

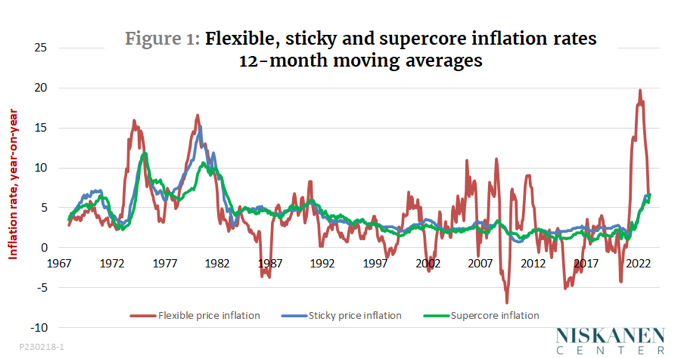

Figure 1 shows year-on-year data for the rate of change of the Atlanta Fed’s sticky and flexible price indexes since 1967. Not surprisingly, the flexible index is the most volatile. At major turning points, changes in the sticky price inflation lags visibly behind changes in flexible price inflation by an amount ranging from half a year to well over a year.

The relative supercore index

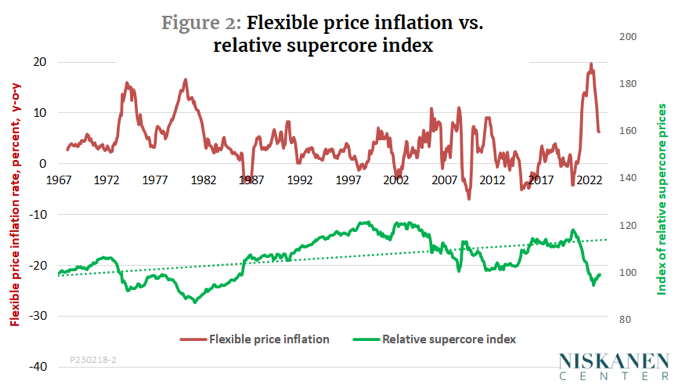

Let’s turn now from the inflation rate of supercore prices to the value of the supercore relative to the flexible CPI. Figure 1 showed the long-term trend of inflation rates, but nothing about the relative level of sticky and flexible prices. Figure 2 provides the missing information. For easy comparison, the top line, measured on the left-hand vertical axis, repeats the rate of flexible price inflation as shown in Figure 1. The lower line, measured on the right-hand vertical axis, shows the ratio of the level (not the inflation rate) of supercore CPI to the level of the flexible CPI, with January 1967 equal to 100. I will refer to this ratio as the relative supercore index. A value above the trendline shows that the nonhousing services in the supercore index are more expensive than usual relative to the goods in the flexible index. Similarly, a value below the trendline shows that increases in the prices of the items in the supercore have fallen behind those of more flexible goods.

Two features stand out in Figure 2.

First, as the trendline indicates, the ratio of supercore to flexible prices has increased by about 20 percent over time when cyclical ups and downs are smoothed out. My best guess is that this trend is largely due to the “Baumol effect.” As William Baumol and W. G. Bowen noted in a 1965 paper, there is a tendency for labor productivity to increase more rapidly in goods markets than in service markets. (It takes far fewer farm workers to harvest a ton of wheat than it did in the 19th century, but the same number of musicians to perform a Beethoven string quartet.) Because of slower productivity growth, the prices of services tend to rise faster than the prices of goods. Since more than 90 percent of the flexible CPI consists of goods while more than 90 percent of the supercore consists of services, the Baumol effect provides a plausible explanation of the upward trend of the relative supercore index.

Second, even a casual look at Figure 2 suggests that the relative supercore index tends to drop below its trend during periods when flexible prices are especially volatile. The stagflationary 1970s are one example. The supercore dropped below trend again in the years around the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, when the flexible-price inflation rate was highly variable, even though not as high as in the 1970s. In contrast, during the period of relative stability from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s – the Great Moderation – the supercore recovered relative to the flexible CPI.[1]

Implications for policy

Back now to our main theme – does targeting supercore inflation make sense? I can think of three reasons why it might not.

Lags matter

The first reason is that monetary policy operates only with a considerable lag. Raphael Bostic, president of the Atlanta Fed, wrote recently that “a large body of research tells us it can take 18 months to two years or more for tighter monetary policy to materially affect inflation.” A recent paper by Taeyoung Doh and Andrew T. Foerster of the Kansas City Fed suggest that because of changes in the way the Fed implements tightening, those lags may be shorter now than they used to be. Even so, the new estimates show a lag of a full year for the effect on inflation and as much as three years for the effect on unemployment, with a wide range of uncertainty.

The Fed did not start its program of rate increases until March 2022. Taken at face value, that would mean we won’t feel the full effects of recent tightening until the fall of 2023 – or later this spring, at the earliest, if the new estimates hold up. Of course, the lag is less for some prices than others. Since supercore prices, by definition, are among the stickiest, it would seem that they would be subject to a lag toward the long end of the estimated range.

Lags matter for policy. If you want to nip an inflationary outbreak in the bud, the time to act is not when you see the relevant numbers starting to climb, but months in advance. Similarly, if you want to head off an impending recession, then you should not wait for unemployment to start rising or for inflation to fall all the way back to its target. You should ease off well before that point.

By that reasoning, critics may be right to say that in retrospect, the Fed would have better controlled inflation had it started to tighten earlier than the spring of 2022. However, continued tightening into 2023 could equally turn out to be a mistake. To see why, we need to understand the role the inflation expectations play in the making of monetary policy.

Forecasting and expectations

In a world with lags, optimal policy calls for action in advance of economic turning points. For that reason, some economists maintain that “inflation targeting” should instead be called “inflation-forecast targeting.” Under such a policy, central banks would cautiously adjust interest rates to keep inflation as close as possible to its forecast path, rather than waiting to raise rates until inflation got out of control.

That being the case, one argument for targeting core inflation is that the core reflects underlying trends in the economy. In contrast, indexes that are strongly affected by the flexible prices of items such as food and energy are more subject to random exogenous shocks. At the same time, central banks should closely monitor inflation expectations, which can be thought of as the inflation forecasts of consumers and producers.

In a methodological paper linked from the home page of the Atlanta Fed’s sticky price index, Michael F. Bryan and Brent Meyer argue that sticky prices have especially close links both to expectations and to future inflation outcomes. In particular, they show that an index of sticky prices provides more accurate forecasts 3, 12, and 24 months ahead than does an index of flexible prices.[2] However, the correlations they observe do not necessarily constitute an argument for using either sticky prices in general or supercore prices as a policy target, nor do they make such an argument.

In particular, it seems questionable whether the relatively high rate of supercore inflation in early 2023 was primarily driven by expectations. Look at the far-right tail of the supercore series in Figure 2. Between May 2021 and May 2022, the relative supercore index dropped by 25 points – its sharpest drop ever. Although it began to recover just a bit in the second half of the year, by February, the relative supercore index had recovered only about a third of the amount by which it had dropped below trend. That being the case, ongoing price increases in the supercore sector may not, after all, reflect service providers’ expectations of ongoing inflation in the economy as a whole. Rather, they may simply be trying to get their heads back above water after two years in which their own prices spectacularly failed to keep up with the rise of wages and the prices of material goods.

If observed correlations among supercore prices, expectations, and near-term inflation outcomes turn out to not to be causal in nature, any attempt to use supercore prices for forecasting or targeting risks running afoul of Goodhart’s law. According to that principle, statistical relationships tend to break down when they are used for policy purposes. The demise of the quantity theory of money and the subsequent abandonment of money-supply targets by central banks are often cited as a case in point.

The health of the supercore

But Goodhart’s law to one side, shouldn’t we welcome the Fed’s efforts to smother inflation in the last stronghold where it survives? As consumers, don’t we consider low bus fares and manicure prices good things in themselves? The answer, I think, is yes – as long as firms remain able to provide a steady supply of high-quality services. But if relative prices of supercore services stay low indefinitely even while their costs have risen, suppliers will sooner or later come under real pressure.

Consider wages. According to the most recent data, 85 percent of privately-employed workers are employed in the service sector and just 15 percent in the production of goods. However, since workers are free to move back and forth between the two, relative wages in the goods and service sectors tend to be more stable than relative prices. In fact, between mid-2021 and mid-2022, while the relative supercore price index was dropping like a stone, wages in the service sector as a whole actually rose fractionally relative to wages of goods-producers.

Clearly, the combination of stable relative wages and dramatically falling relative prices puts the service sector under pressure. Add to that the fact that service firms need many non-labor inputs, such as fossil fuels and motor vehicles, that are sold by goods-producers. Further, add the fact that demand for goods recovered more rapidly from the pandemic than did the demand for services, and you get a picture of a sector at risk. Its cost-price squeeze is going to continue until relative supercore prices claw back at least a good part of the amount by which they have fallen below trend. It hardly seems like the right moment to single out nonhousing service prices for special restraint.

The bottom line

On the whole, I am enthusiastic about the Fed’s incipient moves away from old-style Phillips curve models that lump all prices together as a single variable, whether that is the CPI, the PCE, or something else. In that regard, Powell’s division of prices into goods, shelter, and nonshelter services is a step in the right direction. More detailed models could divide prices into a greater number of buckets, add input-output relationships among sectors, and include other details.

In my opinion, such models are likely to strengthen the case for a more flexible approach to inflation targeting in times of high relative price volatility like the past few years. Yes, it would be great to “Whip Inflation Now,” as a mid-70s policy slogan put it. However, if the current pattern of relative prices is out of whack, freezing it in place may not be a great idea. It would be worth considering giving more leeway for relative price adjustment even though that might slow the rate at which overall inflation returns to target. If the market turmoil that followed the failure of SVB causes the Fed to rethink its plans for further monetary tightening, that may turn out to be a good thing.

[1] A statistical test confirms the visual impression that low values for the relative supercore index are associated with volatile flexible-price inflation. The standard deviation over a moving two-year period of the monthly increase or decrease in the flexible CPI can serve as a measure of volatility. The correlation between that measure and the relative supercore index is negative and statistically significant (R = -.78).

[2] Their paper was published in 2010. It will be interesting to see how their results hold up when more recent data is included.

Photo credit: iStock