Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro shocked political observers on Sunday by vastly overperforming his polling averages in the first round of the Brazilian presidential election and forcing his primary rival, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, into a tense runoff later this month.

Several leading Brazilian political experts have been apprehensive about this outcome because of Bolsonaro’s refusal to accept the possibility of a legitimate defeat, the highly polarized state of the Brazilian electorate, and the complicated ties between Bolsonaro and the Brazilian military. A close election later this month could aggravate the possibility of Bolsonaro refusing to relinquish the presidency in the event of his defeat, which would plunge Brazil into a fully-fledged political crisis.

While much has been written in prominent outlets about the potential geopolitical implications of this scenario, relatively little attention has been paid to one of the side-effects it is almost certain to cause: the mass migration of Brazilians fleeing instability that would exacerbate the hectic state of migration at the U.S. southern border.

In recent years, migratory flows at the southern border have been primarily composed of Mexicans and Central Americans seeking to escape economic and social unrest. More recently, migrants from Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua fleeing socialist regimes have come to the forefront as another grouping of countries currently reshaping migration trends.

Due to these prevailing narratives about who arrives at the border, countries that do not fall within these categories or currently exhibit low migration numbers are often an afterthought. While anticipating future developments always entails a significant amount of guesswork, there is good reason to believe that South America is currently poised to become the next epicenter of migration to the U.S. southern border. In the specific cases of Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, unique circumstances are on a collision course with ingrained dysfunctions to create a new wave of South American migrants.

Brazil

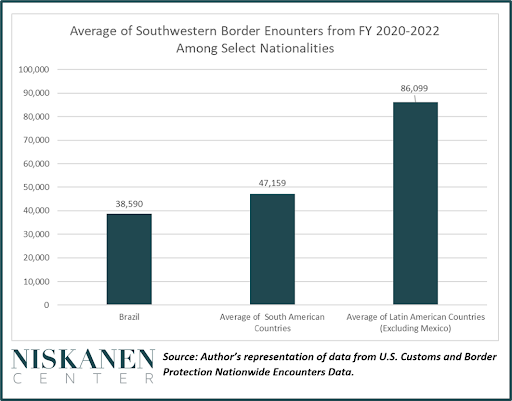

Contemporary border encounters with Brazilians have been far lower than the average for Latin America or South America, even when excluding Mexico. In the past three years, Brazil has averaged 38,590 encounters at the U.S. southern border compared to an average of 47,159 for South America and 86,099 for the rest of Latin America (excluding Mexico).

This matters because Brazil is the most populous country in Latin America, with an estimated 84 million more people than Mexico (the second most populous). In recent years the United States has struggled to effectively address migrant flows from much smaller countries in Central America. In the event of widespread civil unrest, a Brazilian migrant crisis would throw us into uncharted territory.

There is reason to believe some factors would alleviate the crisis. Many Brazilians have ties to European countries, have modest incomes, and may elect to relocate to those countries instead. Indeed, a significant number of Brazilians appear to be already doing so. Unlike Mexico, Brazil is also geographically far less proximate to the U.S., so the incentive to move is not as immediate.

Nevertheless, a sharp uptick in migration from a country of 216 million people that has historically had relatively low migration numbers would inevitably send shockwaves throughout the region.

Colombia

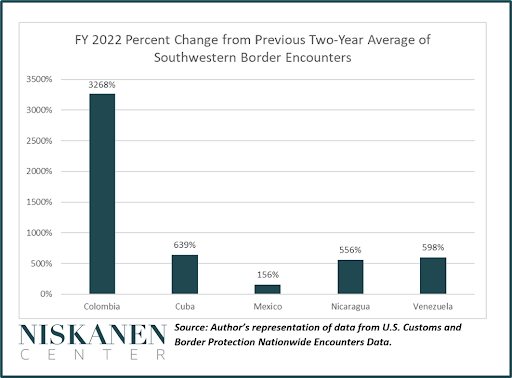

Excluding Ukraine, Colombia has seen the most significant growth of encounters at the southwest border of any country in FY 2022 compared to FY 2021. Considering the averages of previous years, Colombia dwarfs the other four Latin American countries with the highest percentage increases in southwestern border encounters.

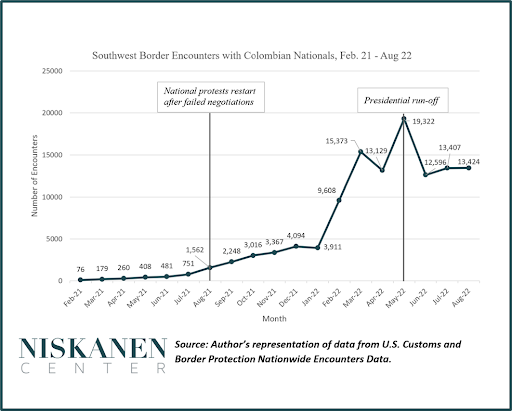

This increase appears to correlate with economic and political anxieties. Colombian encounter numbers have also been historically low but began to increase modestly during the 2021 Colombian Protests. Indeed, the first major uptick in Colombian encounters in August of 2021 could be connected with a breakdown in negotiations between protestors and the government and a renewed wave of national protests. The peak coincided with the lead-up to a presidential primary where two populist candidates advanced to a runoff election amid high levels of dissatisfaction with the country’s direction, and has since remained high amidst ongoing political and economic unrest.

A continued increase in migration from Colombia would also be significant for reasons beyond pure numbers. While Colombia was designated a major non-NATO ally earlier this year, relations under newly-elected president Gustavo Petro have been strained. A large migrant wave could add another complicated factor to our diplomacy with a critical regional partner. Colombia is also home to the highest number of displaced Venezuelans in the world, and worsening conditions risk triggering a secondary wave of Venezuelan migration from Colombia to the U.S. southern border.

Ecuador

It may seem strange to include Ecuador in this list. While Southwest border encounters from Ecuador have been unstable over the past three years, the most recent numbers from FY 2022 show Ecuador at only 14 percent of South America’s regional average of 83,888 encounters.

Despite this, Ecuador’s previously higher numbers are a cause for concern in light of increasing violence in the country. Ecuadorian democracy has been historically weak, and destabilizing events have increased. A bomb planted by criminals in Guayaquil caused at least 22 casualties in August and led to a state of emergency in Ecuador’s second-largest city, while homicides have skyrocketed and renewed strikes and mass protests remain a threat after fresh and tenuous agreements.

As in Colombia, conditions in Ecuador also matter because they are currently home to the third-highest number of displaced Venezuelans in the region. A spillover of migration could put an additional strain on other South American governments.

Conclusion

While other countries may pose more immediate challenges, the U.S. should not lose sight of South America as a potential nexus for mass migration in the coming years.

In preparation for potential increases in migration from these countries, the U.S. could raise the refugee cap for Latin America, which is currently tied for the lowest of any region at 15,000. Unique circumstances in each country will require unique approaches. In Brazil, the U.S. is already sending messages that a clean, fair election is vital. In Colombia, managing relations with the Petro administration and playing a positive and meaningful role in ongoing peace talks with paramilitary groups could help in the short term. And in Ecuador, increased security assistance would help bolster a pro-American government that is otherwise struggling to contain crime.

In the coming months, Brazil may have a smooth transition or continuation of power, Colombia may see an improvement in its economic and political fortunes, and Ecuador may be able to stem its rising crime wave. Still, in case one or more of these scenarios fails to occur, the U.S. should still be prepared with robust policy in place to address the resulting repercussions.

Photo credit: iStock