The popularity of the expanded child tax credit (CTC) has spurred interest in state legislatures to pick up where the federal government has left off. These efforts are laudable and should be a base model for what can be done in states across the country to aid families.

The enhanced federal CTC was a significant turning point in social policy, with policymakers across the ideological spectrum recognizing the value of its ability to aid American households. The credit earned praise on the left thanks to its historic reductions in child poverty and food insecurity among low-income households. On the right, the credit was welcomed for its ability to spark family formation and improve family stability. It is therefore hardly surprising that since the expanded federal CTC’s enactment, additional states have opted to provide the relief to which families have become accustomed.

Picking up the slack

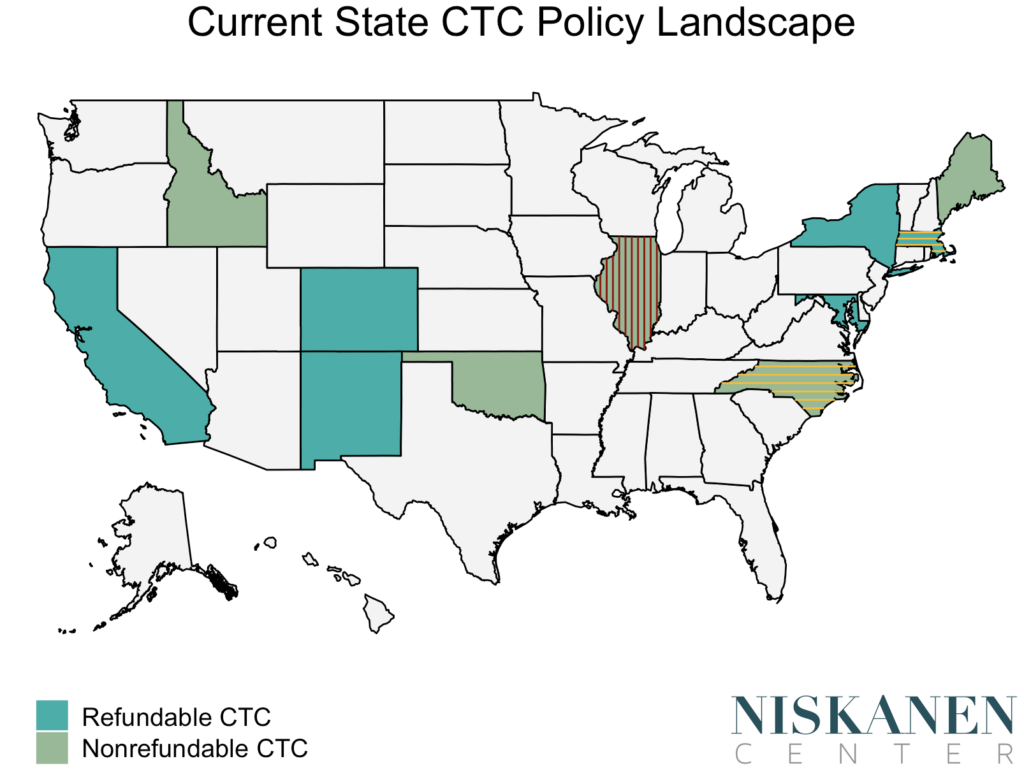

To date, 10 states offer a state-level tax credit: California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Oklahoma. Three of these states—Colorado, Maryland, and New Mexico—drew upon the popularity of the enhanced federal CTC and implemented their state credit shortly after its passing. California and Colorado restrict their benefits to young children, and Massachusetts includes elderly dependents and adult dependents with a disability.

The six states that offer refundable credits—California, Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, and New York—allow families to receive the entirety of the credit regardless of tax liability. Across the board, benefits and eligibility differ substantially from $75 to $175 per child contingent on income in New Mexico to $1,000 per child under six in California.

Source: Niskanen analysis of state laws as of April 2022.

The Governor of Massachusetts has proposed a budget that doubles the size of its credit. Michigan and Vermont have recently passed child tax credits in their statehouse, awaiting further approval. The Michigan credit would provide a $500 credit to most children, and the Vermont bill would grant $1,200 to children under six. Recently, CTC-related legislation was signed into law in Alabama. Since 2019, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia have introduced legislation to create child tax credits.

A path forward

The Build Back Better Act is dead, but state lawmakers do not need to wait for Congress to act. A refundable CTC at the state level could cover families excluded from the current federal CTC and other non-refundable tax credits. The flexible cash benefits would allow families to address their unique financial constraints. Under fiscal restraints, states should also consider prioritizing young children. Younger children tend to have younger parents who are earlier in their careers and have lower average earnings.

Unfortunately, states do not have the federal government’s capacity and funding, making it more difficult to fully replace the federal credit. Still, states can provide substantial benefits, impact child poverty, and alleviate income inequalities. Residents in states with lower average incomes, such as West Virginia—home state to Senator Joe Manchin, who has famously disapproved of bringing back the expanded federal CTC—would especially benefit from receiving the additional assistance a targeted, fully refundable, state-level reform would provide.

Most state and local tax systems are regressive, with low-income households paying higher effective tax rates. Spending on children at the state level varies substantially, and the inflation erosion of TANF, which has lost 40 percent of its value since 1997, limits the impact of current assistance. Current state-level CTCs are also generally not indexed to inflation, so expanding the credit further will fill these gaps. State-level CTCs would make the tax code less regressive and fill the spending gap for households with children, particularly low-income households. A refundable credit offers families an opportunity to put food on the table and afford family-based care.

States could use Massachusetts as a model, which created a de facto CTC and converted a deduction for dependents into a refundable tax credit for children and other adult dependents, the Household Dependent Tax Credit (HDTC), and the Dependent Care Tax Credit (DCTC) respectively. There are currently 25 states with a Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, which could be converted into a refundable CTC. A recent Niskanen brief explores various reform options that underscore how valuable a tool implementing a refundable tax credit is for households.

State policymakers should embrace the numerous benefits of the federal child tax credit and pursue a version in their respective states. Even modest benefits can provide income support to low-income households and support families. New and current proposals should heed the lessons of current state-level laws and adopt a refundable credit that delivers the most significant benefits to those who need the most support.

Photo credit: iStock