Last month, 4,100 unaccompanied alien children (UAC) crossed into the United States through the southwest border; all told, nearly 62,000 children have arrived over the past six months fleeing violence, drug trafficking, and gangs in the Northern Triangle. The Obama administration attempted to stem the flow by better securing the border, delivering aid to countries with the most children in need—like Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—and by allowing some migrants to apply for relief from within their home countries.

Without these programs to partially stem the tide, children are again making the dangerous trek to U.S. borders in large numbers. If the goal is to check the flow, why are we not encouraging UACs to apply for refugee status, as opposed to asylum? In short, because of a lack of administrative resources.

Asylees & Refugees

Our humanitarian laws provide for a number of different avenues of protection for a UAC, which is an unaccompanied child under 18 years of age, with no lawful immigration status in the U.S., and who has no parent or guardian in the U.S. In 2015, the number of asylum seekers from the NTCA region reached 110,000—UACs accounted for most of the surge.

The most well-known status pursued by UACs is that of an asylee, which is a distinct population from refugees. An asylee is an alien in the United States or at a port of entry who is seeking protection because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution if they return to their native land.

Persecution, or the fear thereof, must be based on the individual’s race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. For example, the political opponent of a powerful regime who suffered imprisonment or threats due to his political beliefs is an appropriate candidate for asylee status.

Eligibility for refugee status turns on an applicant’s physical presence in a third country that is neither the United States nor their home, and the ability to apply through our refugee system, which requires a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) presence nearby, and U.S. officials to administer interviews, background checks, and processing.

However, since many of the neighboring countries in the Northern Triangle of Central America (NTCA) are equally dangerous for children, it is difficult for them to leave their home country and temporarily resettle in surrounding areas. Thus, in 2014, the Obama administration launched an in-country refugee/parole program—the Central American Minors (CAM) Program—to try to stem the tide of UACs arriving at the southwest border of the U.S. and provide children a safer option to seek protection in the U.S.

CAM allowed parents who were lawfully present in the U.S. to apply for refugee status for an unmarried child in a NTCA country. Under the program, even if a child did not qualify as a refugee, evidence of danger or threat of harm was enough to allow for two-year, renewable parole in the U.S. Each child was processed as a refugee, and DNA testing was used to confirm their familial relationship; those who did not qualify but were still found to be at risk were eligible for parole—permanent entry into the U.S. for humanitarian purposes.

CAM was expanded in 2016 to allow some of those accompanying a qualifying child to also apply for refugee status on the same application. Each of these additional individuals had to qualify on their own for refugee status. By the end of 2016, 10,700 children and family members had applied for refugee status through this program, and 960 of them were successfully resettled in the U.S.

Later in 2016, the U.S. created the Protection Transfer Agreement (PTA) Program with Costa Rica, which allows up to 200 refugee applicants at a time to stay in Costa Rica while their applications are under review. This program was meant to protect refugee applicants facing death threats from gangs, police, or soldiers while they awaited a decision.

About 1,500 minors had status in the U.S. and another 2,700 had conditional approval (but had not yet entered) when President Trump ended the program in August 2017. Those with conditional approval were not admitted.

Refugee Pitfalls

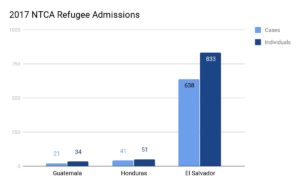

Even though the Trump administration ended in-country processing, there should still be higher numbers of UACs pursuing refugee status, but refugee admissions from NTCA are low. According to the Refugee Processing Center, the U.S. admitted just 913 refugees from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in FY 2017 after reviewing only 700 cases (one case can involve multiple refugees).

Two factors likely keep UACs from pursuing refugee status: 1) ineligibility; 2) the lack of administrative resources.

A number of scholars argue that the limited definition of refugee precludes most UACs because it only contemplates state-sponsored persecution, rather than forced conscription and gang recruitment, and because it does not include gender discrimination.

But persecution is a broad concept. As the Ninth Circuit noted, “Persecution covers a range of acts and harms,” and “[t]he determination that actions rise to the level of persecution is very fact-dependent.”

In recent cases, physical violence, torture, severe human rights violations, serious threats of harm, unlawful detention, and substantial economic discrimination or harm inflicted by either a government, or authorities within a country that the government is unable to control, have risen to the level of eligible persecution. Theoretically, this could encompass a number of UACs in the NTCA region.

However, even if UACs have credible claims of persecution, the lack of administrative and processing resources in the region may still stymie their ability to get refugee status. UNHCR has just one national office in each of the three NCTA countries, respectively. Although there are additional urban processing centers, the limited availability of offices is stark in the region.

UNHCR Global Focus—Latin America; last updated October 2017

In contrast, there are more than 8 major centers spread across Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, and Ecuador.

The final barrier to status as a refugee is not only the national cap—set egregiously low at 45,000 by President Trump in September 2017—but the regional limit as well. The administration has set the regional ceiling for Latin America and the Caribbean at just 1,500 refugees for FY 2018.

A Few Potential Fixes

Congress—once again—has an opportunity to better respond to this humanitarian nightmare.

Initially, the U.S. should codify the CAM and PTA programs. These measures will increase our ability to provide a safe haven to those on the run, ensure children in danger are protected, and enable the agencies working to help these refugees to do their jobs to the best of their ability. This would also reduce the number of migrants seeking asylum in the U.S. at the southern border, which would both reduce the massive backlog in the asylum system, and increase security at the border.

But most importantly, changes should be made to the refugee law to explicitly include those who are fleeing gang violence. This could be done by including a gender nexus, allowing those fleeing gender-based persecution to qualify for refugee status.

The law could also be changed by recognizing broader, more inclusive social groups, which are groups recognized by society as distinct classes of people facing persecution because of that group membership. Such groups might include “those fleeing gang retaliation because they are witnesses to crimes” or “girls and women fleeing sexual violence and/or exploitation at the hands of gangs.”