The Biden administration recently announced four new “workforce hubs”: areas of the country that will be receiving substantial investments in building a renewed technology sector in America, using funds from previously passed legislation, including the American Rescue Plan, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and The CHIPS and Science Act. The four new hubs announced are Upstate New York, Michigan, Milwaukee (WI), and Philadelphia (PA). This is in addition to the five hubs previously announced in Columbus (OH), Baltimore (MD), Pittsburgh (PA), Augusta (GA) and Phoenix (AZ).

The program’s goal is to “ensure all Americans can access the good jobs created by the President’s Investing in America agenda”. But are these locations the best suited for obtaining this goal?

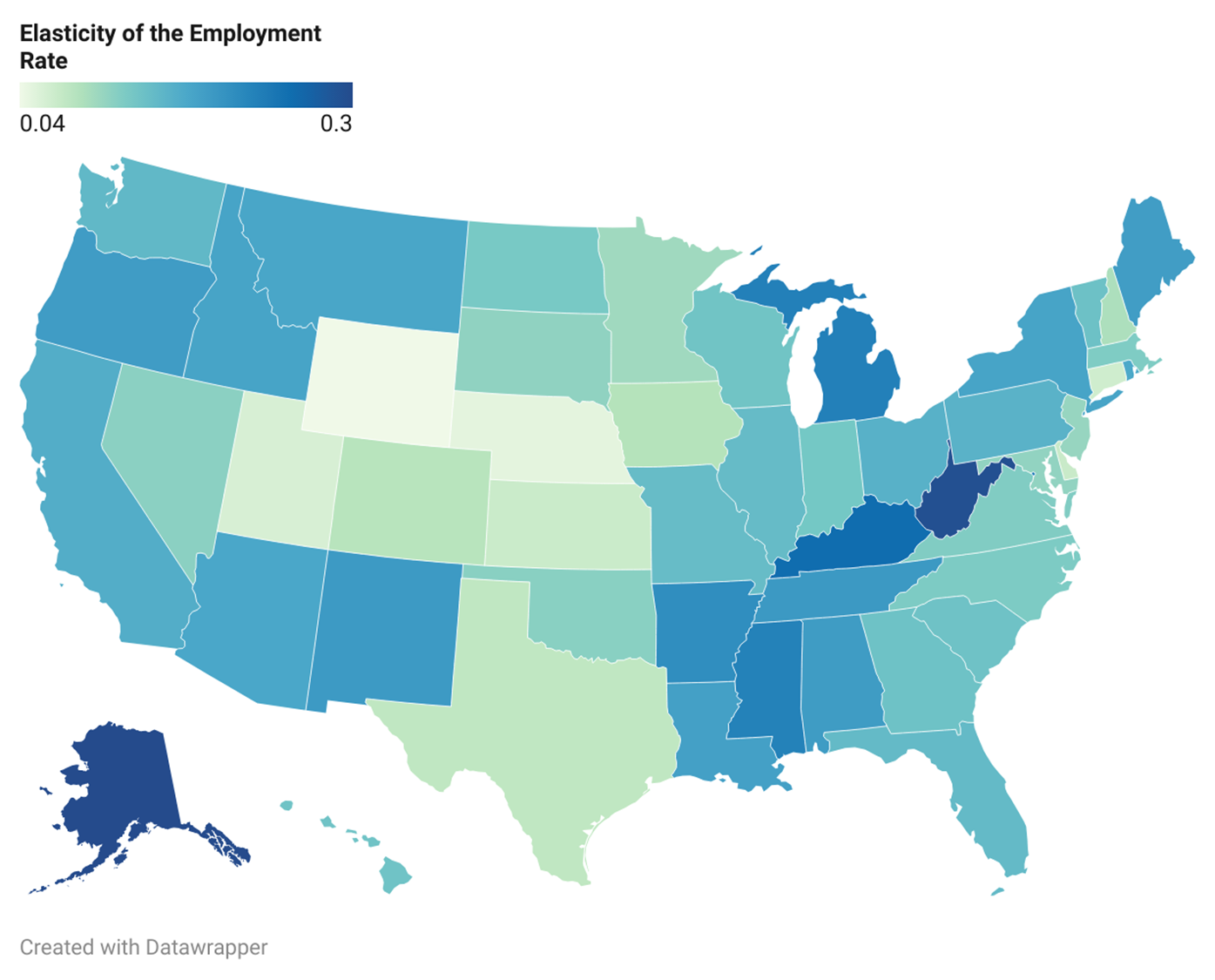

A 2019 Brookings Paper by Benjamin Austin, Ed Glaeser, and Larry Summers can help provide an answer. Austin, Glaeser, and Summers (AGS) proposed that “place-based funding” should be allocated in part based on the “elasticity of employment” in different areas. In some states, it’s hard to raise employment very much – almost everyone already has a job. In other states, there’s a substantial population who has, for whatever reason, left the workforce. Looking at each state’s history of prime-age male employment rates and estimating shocks to labor demand allowed AGS to create estimates of the elasticity of employment for each state. They point to Wyoming as an example of a low elasticity state (most people are employed – labor demand shocks cannot increase employment rates) and West Virginia as a high elasticity state (West Virginia has low employment and is responsive to shocks).

We replicated AGS’s analysis for each state in Figure 1 below. High-elasticity states (Alaska, Kentucky, West Virginia) are in dark blue, while low-elasticity states (Nebraska, Utah, Wyoming) are in light blue or white.

Using this metric, are the states with designated “workforce hubs” well-targeted? No.

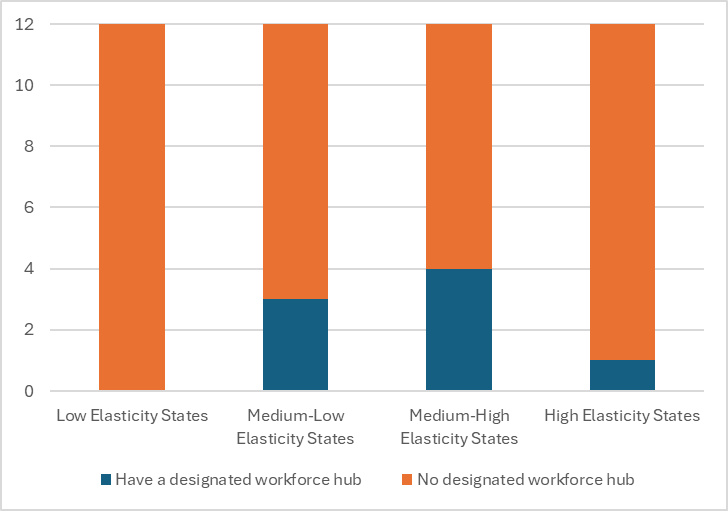

For example, take the contiguous 48 states (i.e., excluding Alaska and Hawaii) and divide them into four groups of twelve: low-elasticity states, medium-low-elasticity states, medium-high-elasticity states, and high-elasticity states. If the workforce program hub program was effectively targeted, we’d expect more high-elasticity states to receive funding than low-elasticity states.

None of the low-elasticity states received funds, suggesting some attention was paid to this issue. In these states, any additional funding is unlikely to create more jobs. At best, these states (many of which already have high levels of economic development) would have somewhat higher wages. On the other hand, three medium-low states (Maryland, Wisconsin, and Georgia) are receiving funding. Four states in the medium-high elasticity group received funds. In the high-elasticity group, only one state, Michigan, received funds. Employment elasticity has played a limited role in the targeting, not much better than chance.

There are a few caveats. While the Biden administration is primarily focusing on cities and subregions, the “elasticity of employment” figures have only been calculated at the state level. It’s plausible that Baltimore, for instance, has a relatively high elasticity of employment, even if Maryland as a whole does not. However, “elasticity of employment” should not be the sole focus of industrial policy – the specific needs of industries are also crucial. New York and Arizona might have specific existing infrastructures that make them well-suited for semiconductor investments, which might not be applicable to the high elasticity of employment states like West Virginia or Kentucky. This understanding of industry-specific needs is key to ensuring informed decision-making.

There’s also a potential cynical interpretation. Perhaps the Biden administration is targeting these funds based on political needs, not necessarily where the money would be best spent. The website fivethirtyeight.com lists seven swing states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Nevada, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. Five swing states have designated workforce hubs, compared to three of the forty-three non-competitive states. If those states are the best suited for workforce investment, it’s certainly convenient.

No matter what the reason, the funds could be more directed towards high-need areas. And there’s a precedent for using these sorts of funds to shore up left-behind regions. For example, NASA has sometimes been called the Marshall Plan for the Confederacy since it created new high-tech industries in the country’s poorest areas, including the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama and the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Alabama and Mississippi are still high employment elasticity states today and should be considered as potential workforce hubs. If they could support the rocket industry in the 1960s, why not the semiconductor industry today?

Place-based industrial policy necessitates a delicate balance. The goal is to ensure that the funds are allocated in a way that improves our industrial capacity and prioritizes areas with the greatest need. To successfully build up the economy from the “bottom-up,” it’s crucial that future resources are targeted to the states where the jobs are most needed.