Key Takeaways

- The Family Security Act 2.0 from Senators Romney, Daines and Burr is a framework to transform the Child Tax Credit into a robust child benefit that rewards work, promotes marriage, and simplifies the tax code.

- Mirroring the recommendations of the Taxpayer Advocate Service, the FSA 2.0 proposes restructuring the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) into a simplified worker benefit that would reduce marriage penalties and sources of complexity that lead to improper payments.

- A recent report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) raises legitimate concerns that the FSA 2.0’s proposed credit values fail to ensure a subset of EITC-eligible single parent households are kept whole.

- One reason is inflation: While the EITC is indexed for inflation, the credit values of the FSA 2.0 have not been updated to reflect the recent rise in prices, making it less effective at replacing the value of the current EITC than in its original incarnation.

- This report outlines options for adjusting the FSA 2.0’s credit values to close the benefit gap created by the EITC overhaul without sacrificing the core structural advantages of the reform.

- In the process, we show that the CBPP’s arguments against consolidation are overstated, and fail to appreciate both the harms created by marriage penalties and the net benefits of the FSA 2.0 to families over time.

How to Fix Marriage Penalties Without Leaving Single Parents Behind:

Closing the Family Security Act 2.0’s benefit gap

Senators Mitt Romney, Steve Daines, and Richard Burr recently unveiled the Family Security Act 2.0 (FSA 2.0), a framework for an expanded child benefit that builds on Romney’s original proposal from 2021. The FSA 2.0 would transform the Child Tax Credit (CTC) into a child benefit of $3,000 per child aged 6-17 and $4,200 per child under age six. The expansion would be fully paid for by consolidating several other tax benefits in a manner designed to simplify the tax code and reduce marriage penalties, including a significant restructuring of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

A streamlining of refundable tax credits to better distinguish between child benefits like the CTC and worker benefits like the EITC is long overdue. While the EITC is structured as a wage subsidy, it includes a large, embedded child benefit because the maximum allowable credit increases with the number of kids. Shifting the EITC’s per-child variation into the CTC would help to clarify the distinct purposes of the two credits — helping low-wage workers versus helping households with children — leading to a simpler and more legible tax and benefit system.

Nevertheless, a recent analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) raises legitimate concerns about the net impact of the FSA 2.0 on certain household configurations. In particular, after praising the FSA 2.0’s child benefit structure, the report accuses Senators Romney, Daines, and Burr of financing the expansion of child benefits at the expense of “single parents with low and moderate incomes.” The concern originates from how FSA 2.0’s reforms to the EITC and Head of Household filing status interact to create a net loss in credits among a subset of single-parent, EITC-eligible households.

Fortunately, the benefit gap created by the EITC overhaul is small enough to be fully eliminated without undoing the core structure of the reform. Indeed, as we discuss in detail below, the CBPP analysis overstates its case against the FSA 2.0’s proposed consolidations, and fails to appreciate both the harms created by marriage penalties and the net benefits of the FSA 2.0 to families over time.

The EITC pays you to not get married

The proposed improvements to the EITC are motivated in part by the large marriage penalty built into its current design. Marriage penalties occur when a couple would lose benefits or pay more in taxes for no other reason than marrying, and they are disturbingly common across U.S. safety-net programs. For example, simulations find the average EITC-eligible woman can expect to lose approximately $1,300 in EITC benefits in the year following marriage, or about half of her pre-marriage benefit.

The CBPP dismisses the importance of marriage penalties, arguing that “marriage incentives have at most modest effects on marriage decisions.” Yet how modest is modest? To support its claim, the report includes a citation to a 2013 study that finds “a $1,000 change in the financial incentive for marriage has a 1.7 percentage point effect on the probability of marriage” — an effect that increases among households with less education. Also cited is a 2020 research brief on marriage penalties that, among other things, summarizes a question from the 2015 American Family Survey that found “31 percent of survey respondents indicated they knew someone who had chosen not to marry out of fear of losing ‘welfare benefits, Medicaid, food stamps, or other government benefits.’”

Whether or not the survey and empirical evidence on marriage penalties is meaningful may be in the eye of the beholder. Last month, the CBPP dedicated a blog post to a study that found an additional $1,000 in support from the EITC at infancy led children to earn 1 to 2 percent more in their twenties — a relatively modest result that they, nonetheless, chose to highlight rather than downplay because of its importance. Yet the harms from marriage penalties are important in their own right. This is all the more true in means-tested programs where the interaction of multiple income and eligibility requirements can cause marriage penalties to become substantial, while raising effective marginal tax rates on near-poor households to as high as 90 percent.

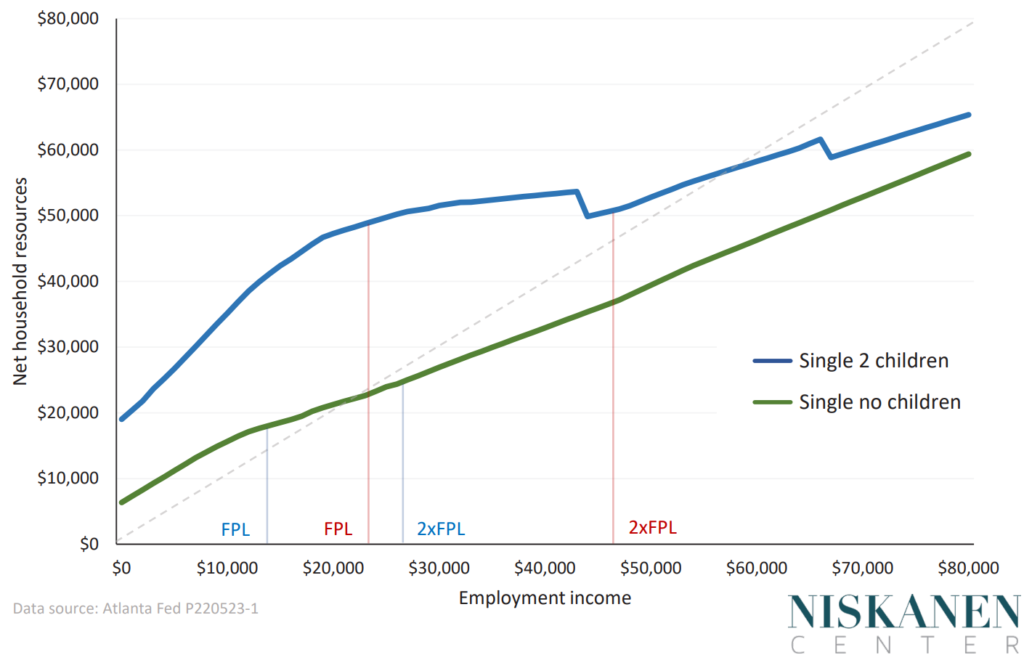

Figure 1: Effective marginal taxes for a single parent of two children receiving Medicaid, SNAP, and the EITC can be as high as 90 percent just beyond the poverty line.

If an EITC recipient also participates in other means-tested programs (such as SNAP, Medicaid, or housing vouchers), the penalty to marriage can easily exceed 15 percent of a family’s income. If these and related marriage penalties didn’t exist, the marriage rate for single mothers with incomes below $26,000 would rise from 9.4 percent to 23 percent, according to a new economic model from the Atlanta Fed. In the words of the model’s authors, the U.S. tax and benefit system “is keeping almost 14 percent of low-income young females with children from getting married in a given year.”

There is more than money at stake here. The greater stability and resources offered by committed, two-parent households suggests that effectively paying single parents to stay unmarried has negative consequences on child well-being in both the short- and long-term. Consider that children born to cohabiting parents have lower birth weight than those born to married parents of similar socioeconomic status and that child health subsequently improves among cohabiting parents who marry compared to parents who only stably cohabit. Whether or not these and related findings justify policies to actively promote marriage, the basic principle of horizontal equity demands tax policy be at least neutral.

Recognition of the severity of the EITC’s marriage penalty has grown in recent years thanks to congressional testimony and the research quantifying its impact on marriage rates, yet reform has been slow to materialize. The challenge of reforming the EITC into a dedicated worker benefit stems from the credit’s historical role in the welfare reforms of the mid-1990s. While the EITC first appeared in 1975, it was greatly expanded in 1993 as a tool to incentivize the transition of single mothers from welfare into work. The largest credits were thus deliberately targeted to single households with dependent children whose incomes fall just below the poverty line. Such narrow targeting makes the current EITC efficient at reducing the “headcount” poverty rate (i.e., at moving households with dependents just across the poverty line), but at the cost of entrenching a sizable marriage penalty. Proposals that seek to fix the EITC alone are usually either expensive or risk creating net losers among a subset of single parents. By reforming the EITC and CTC simultaneously, the FSA 2.0 presents a unique opportunity to reduce marriage penalties in a way that can, at least in principle, ensure all households are kept whole.

EITC households under the FSA 2.0

The crux of the CBPP critique is that the FSA 2.0’s reforms, as currently structured, fall short of keeping many single-parent households truly whole. It is true that FSA 1.0 had a much more modest benefit shortfall in comparison with its successor. One reason is inflation: While the EITC is indexed to the price level, the credit values of the FSA 2.0 have not been updated to reflect the recent rise in prices. That makes FSA 2.0 less effective at replacing the value of the EITC than in its original iteration, as illustrated in Figure 2.

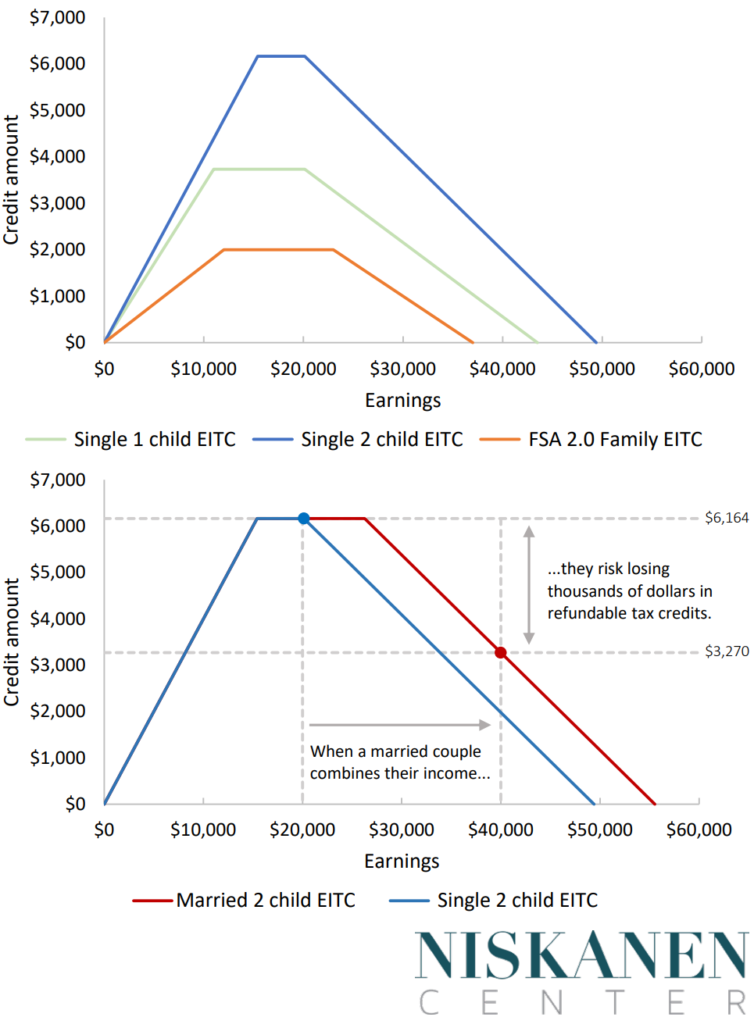

Figure 2: Under current law, the EITC contains an embedded child benefit that steps-up dramatically with a household’s second child, exacerbating marriage penalties.

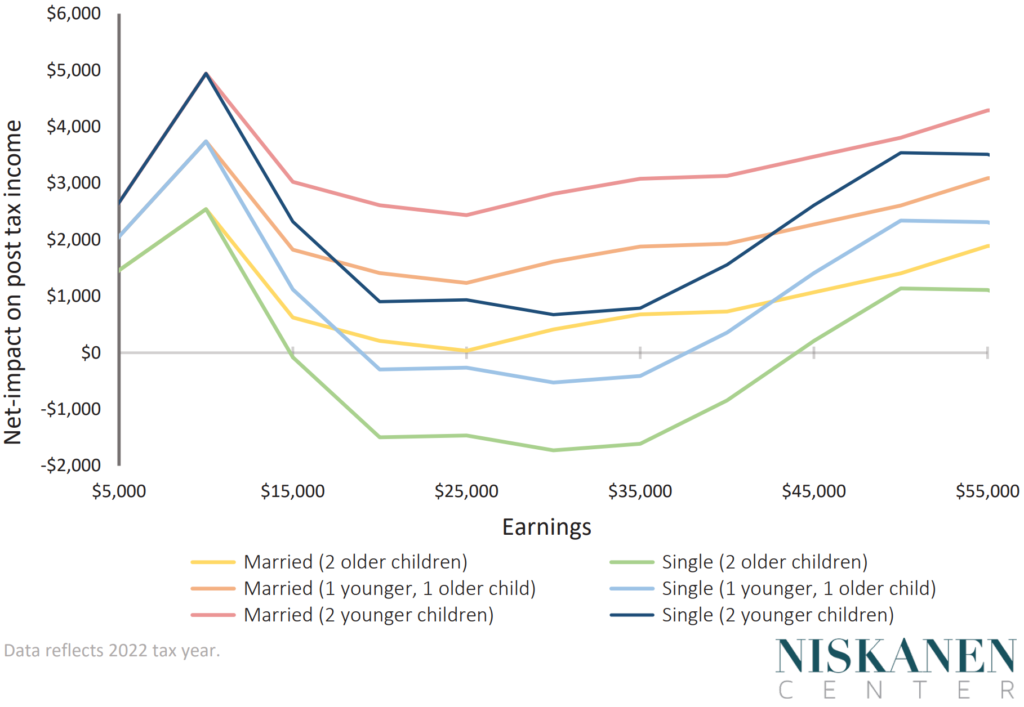

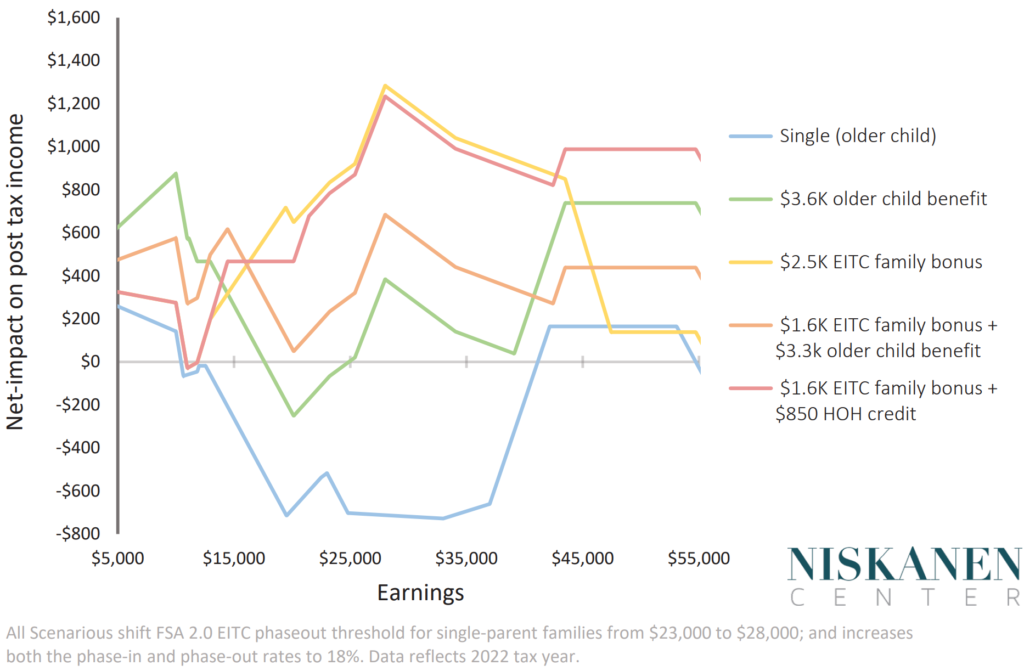

Nevertheless, the FSA 2.0 would still put a substantial dent in child poverty. In our earlier analysis, we found the proposal would reduce child poverty by approximately 12.6 percent, representing just over a million fewer kids in poverty. Indeed, the vast majority of families come out ahead relative to current law, including a big boost for households with earnings below $15,000. Nonetheless, some households could come out worse off in any given year, with the largest net losses concentrated among single parents with two older children and earnings at or around the current EITC’s benefit plateau, as shown by the light blue line in the figure below. Households in this group risk receiving fewer benefits relative to current law given the FSA 2.0’s failure to update its benefit levels to reflect inflation. However, the scope of the net loss is dramatically reduced when considered over the course of a child’s life, if one or both children are below the age of six, or if the parent decides to marry or have a third child, as illustrated below.

In dollar terms, an unmarried EITC recipient with two older children represents the worst-case scenario for static (i.e., single-year) net losses because of the current EITC’s large step-up in value for single households with a second child. Nonetheless, most household configurations are still better off due to the combination of the larger benefit for young children, the closure of marriage penalties, the extension of child age-eligibility to 17, and what is on net a more generous package for larger families.

Figure 3: Net impact of the FSA 2.0 on households with two children relative to current law by household type and age of child.

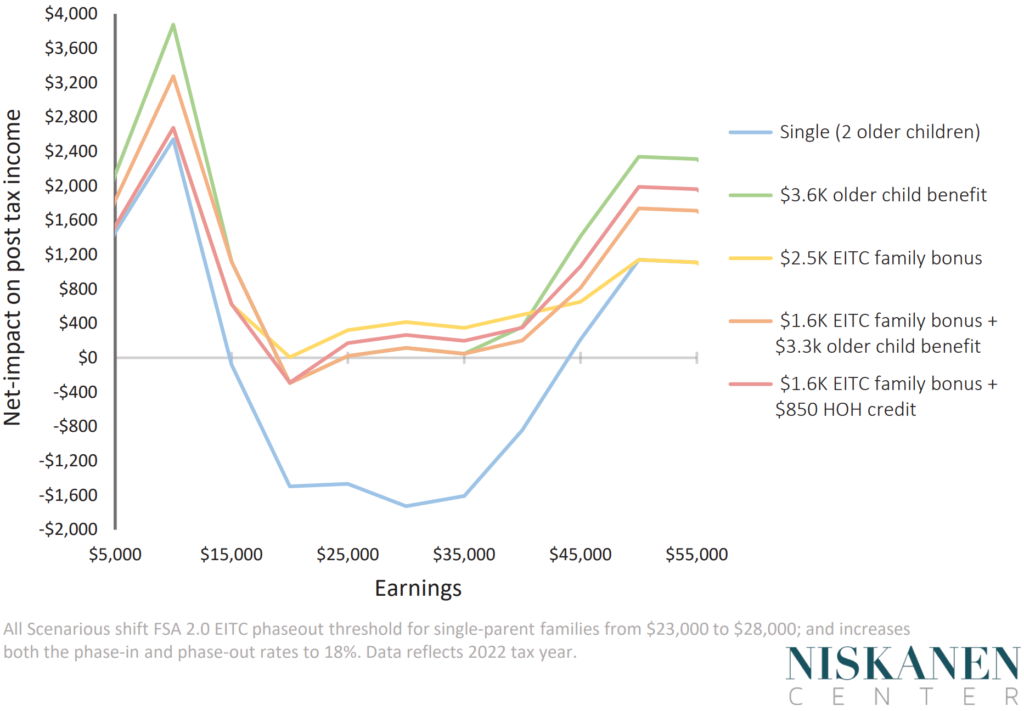

Fortunately, simple modifications to the FSA 2.0 can erase the benefit gap and ensure that all family structures are unambiguously better off. As a first step, the FSA 2.0’s single-parent EITC phase-out threshold could be moved from $23,000 to $28,000 while increasing the phase-in and phase-out rates to 18 percent. This higher phase-out threshold is an important change to keep up with indexation and ensure benefits are held constant over the income range where the current EITC phases out steeply.

The value of one or a combination of the FSA 2.0’s credits could then be increased to fill any remaining gap and make up for the inflation that has eroded benefit adequacy since the original proposal was drafted. Options include but aren’t limited to:

- Increasing the older child benefit from $3,000 to $3,600;

- Increasing the EITC family bonus from $1,000 to $2,500;

- Increasing the EITC family bonus from $1,000 to $1,600 while increasing the older-child benefit to $3,300;

- Increasing the EITC family bonus from $1,000 to $1,600 while implementing an $850 nonrefundable credit for heads of households.

Each of these options has different distributional and budgetary tradeoffs and impacts on marriage penalties. Depending on the approach taken, adopting any one of these options will require approximately $20 to $40 billion in additional offsets or revenue sources to remain deficit neutral.

Figure 4: Options for modifying the FSA 2.0’s credit values to close the benefit gap for single households with 2 older children.

Increasing the older-child benefit by $600 would be the most costly but would benefit the most households. Increasing the EITC family bonus by an additional $2,500 would provide the clearest net benefit to single-parent EITC recipients, but the bonus would need to be similarly expanded for married EITC recipients to avoid recreating a penalty, greatly reducing the scope of the consolidation. Alternatively, the older-child benefit and family bonus could both be increased by $300 and $600 respectively, as if adjusting both to make up for recent inflation.

Alternatively, a $600 increase in the EITC family bonus could be paired with an $850 nonrefundable head of household tax credit. This last option would represent a partial retreat from the FSA 2.0’s abolition of the head of household (HoH) filing status, maintaining only the value of the HoH tax-advantage captured by lower-income single-parent households. As currently structured, the HoH filing status is a source of marriage penalties and tax complexity with benefits that flow disproportionately to higher earners. Nonetheless, converting the HoH filing status into a nonrefundable credit would still be a substantial improvement over current policy, and could even be phased out at higher incomes.

Figure 5: Any of several options for updating the FSA 2.0’s credit values would also close the benefit gap for single households with one older child except in narrow edge cases.

These tweaks would also serve to close the smaller benefit gap for single parents with one older child. In fact, with few exceptions, any of the above options would fill the benefit gap for virtually all households, regardless of family structure, with the exception of narrow edge cases that become net beneficiaries when considered over time.

The focus on static outcomes is misleading

Evaluating the impact of the FSA 2.0’s reforms over time, rather than in a single year, is critical. Consider the option of increasing the older-child credit by $600, as represented by the green line above. While this change to FSA 2.0 manages to close almost all of the benefit gap for single-parent households with one older child, a $200 net loss still remains for incomes at precisely $20,000 — the “sweet spot” for maximizing this household type’s refund under current law. If this household’s income remained exactly the same, year over year, what is otherwise a small reduction in a one-time refund would start to add up. Yet this household’s income (and thus its true net benefit) is all but guaranteed to vary over time, whether due to normal sources of income volatility, changes in family size or structure, or changes in work effort and earnings.

Nor can low-income households be treated as a fixed group. Across the earnings lifecycle, a typical household will see their income grow with age, education, experience, not to mention the broader economy. In any given year, the lowest-earning households also contain many otherwise middle-income families that experienced an income shock or poverty spell. In fact, across the life cycle, approximately 60 percent of Americans spend at least one year below the official poverty line. The FSA 2.0’s relatively flat child benefit structure would thus provide families a greater degree of social insurance, including single-parent EITC households whose incomes fall below $15,000.

The FSA 2.0’s true impact can also be distorted by failing to consider plausible incentive effects. As discussed above, the reform’s reduction in marriage penalties may enable some fraction of single parents to marry their partners. The child benefit’s rapid phase-in may draw hundreds of thousands of nonworking parents into the labor market. And the reduction in effective marginal tax rates may incentivize near-poor households to increase their work effort on the margin. The FSA 2.0’s incentives across each of these dimensions — marriage, labor force participation, and work effort — are aligned to offer larger benefits to a wider pool of recipients, a factor that simply isn’t accounted for in the CBPP’s analysis.

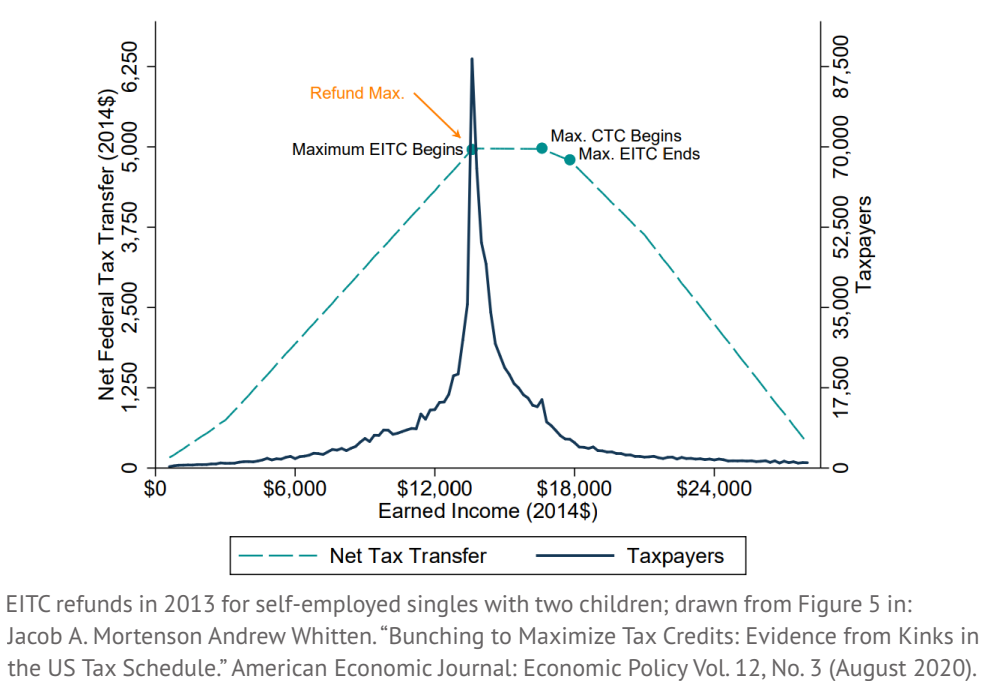

That EITC-eligible households respond to incentives is undeniable. Consider the fact that EITC claims tend to bunch around the credit’s first “kink point,” i.e., where the current EITC plateaus. This shows that households adjust their reported earnings in order to maximize their refund, most often using income from self-employment. Were the FSA 2.0 adopted into law, we would likewise expect to see a change in how EITC households report their income in order to maximize their benefit.

The CBPP’s focus on a static distributional analysis is thus inherently misleading. Beyond ignoring incentive effects, it neglects the cumulative impact of the reformed benefit structure over time, from the extension of eligibility to parents 4 months prior to their child’s birth and the larger benefit for young children to the inclusion of millions of 17 year-olds who are ineligible under current law.

Simplification matters

The FSA 2.0 is designed to reduce the administrative kludgeocracy that currently plagues refundable tax credits. While the benefits of tax simplification don’t show up in distributional estimates, they are arguably substantial. Under current law, over 20 percent of EITC-eligible families fail to claim the credit in a typical year, and among recipients, 60 percent rely on paid tax preparers that capture as much as 13 to 22 percent of the benefit in fees. Adjust for non-participation and fees to tax preparers, and the poverty impact of the EITC may be cut by as much as half.

The complexity of EITC harms recipients and taxpayers alike. The IRS estimates that 24 percent of all EITC refunds issued in 2020 were in error, representing $16 billion in improper payments. In turn, the EITC accounts for over 40 percent of annual IRS audits of individuals, subjecting thousands of low-income households to a bureaucratic nightmare that can result in “due diligence” penalties and even a temporary loss of eligibility.

As a 2019 CBPP report notes, the majority of overpayments in total dollar terms are the result of the EITC’s rules for claiming a qualifying child:

“The EITC is one of the most complex elements of the tax code that individual taxpayers face. The IRS instructions for the credit are nearly three times as long as the 15 pages of instructions for the Alternative Minimum Tax, which is widely viewed as difficult. The EITC’s complexity results in significant part from efforts by Congress to target the credit to families in need and thereby limit its budgetary cost.

EITC overpayments often result from the interaction between the complexity of the EITC rules and the complexity of families’ lives. The Treasury Department has estimated that 70 percent of EITC improper payments stem from issues related to the EITC’s residency and relationship requirements, which are complicated; filing status issues, which can arise when married couples file (often following a separation) as singles or heads of households; and other issues related to who can claim a child in non-traditional family arrangements.”

The FSA 2.0 would help reduce improper EITC payments in a number of ways. Reducing the per-child variation in the EITC would mitigate the complexity of its qualifying child rules. Eliminating the HoH status and EITC’s implicit marriage penalty would reduce errors connected to the use of the wrong filing status. And by shifting child benefit administration from the IRS to the Social Security Administration, the FSA 2.0 stands to increase overall participation rates, maximizing the impact of billions of dollars in refundable tax credits that currently go wasted or unclaimed.

Yet the idea of reforming the EITC and CTC into distinct worker and child benefits is by no means original to Senator Romney. On the contrary, it mirrors the long-standing recommendation of the Taxpayer Advocate Service (TAS), the independent organization within the IRS that exists to represent the interests of taxpayers. As they wrote in a recent blog post,

“TAS has long advocated for dividing EITC into two credits: (i) a refundable worker credit based on each individual worker’s earned income without regard to the presence of qualifying children, and (ii) a refundable child benefit. For wage earners, claims for the worker credit could be verified with nearly 100 percent accuracy by matching claims on tax returns against Forms W-2, significantly reducing improper payments on those claims. The portion of EITC that varies based on family size could be combined with the Child Tax Credit into a larger family credit.”

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is precisely what the FSA 2.0 aims to do. Yet the details matter. If the FSA 2.0 gains momentum in Congress, lawmakers must take the concerns highlighted by the CBPP to heart and fine-tune the reform to ensure clear net-benefits for current EITC recipients, even if it requires finding additional offsets. Less reasonable, however, is the CBPP’s call for policymakers to “reject outright” any EITC consolidation whatsoever. Such an intractable position is at odds with the needs of families, and a sure-fire way to kill any future potential for bipartisan compromise.

Conclusion

The FSA 2.0 would cut child poverty by 12.6 percent while greatly simplifying the U.S. family tax and benefit system. Nevertheless, a subset of low-income parents would receive less in a given year than under current law. This largely owes to past EITC expansions, which narrowly targeted sizable child benefits to a subset of near-poor single parents, entrenching a large marriage penalty in the process. The FSA 2.0’s credit values have also become less adequate given recent inflation. This report outlined a set of simple adjustments to the FSA 2.0 that would fully close its benefit gap without sacrificing the reform’s core structural advantages.

Samuel Hammond is the director of social policy at the Niskanen Center. His research focuses on the effectiveness of cash transfers in alleviating poverty, and how free markets can be complemented by robust systems of social insurance.

Robert Orr is a social policy analyst at the Niskanen Center. His research focuses on social insurance, health care, and labor market issues within the social policy team.

Photo Credit: iStock